I’ve been meaning for some time to write about the AI-photo controversy involving the photographer Boris Eldagsen and the Sony World Photography Awards. The short version: Eldagsen is a photographer whose current work involves the (very sophisticated) use of AI to develop images that look like photos, but aren’t.

He submitted one of these to the Sony World Photography Awards, and won a prize. He declined the prize, noisily, because he said it wasn’t a photograph. Lots of the details of the ensuing spat are online, partly because almost all of this content is curated by him on his own website, in multiple languages.

I’m not that interested in the argument between him and the awards organisers CREO, although they maybe weren’t paying as much attention as they should have been. I’m more interested in the argument about whether this is photography or not.

But first, I’m going to use the relevant image, which is Eldagsen’s copyright, because it’s hard to have this discussion without seeing it.

Image generator

The image was created using DALL-E 2, an image generator developed by OpenAI. The Art Newspaper has this account:

In his submission, Eldagsen described the image as “a haunting black-and-white portrait of two women from different generations, reminiscent of the visual language of 1940s family portraits”.

After the prize was announced, he interrupted a presentation at the awards to make it clear that he wasn’t accepting it—he says he did this because he’d only realised when in the room that despite having won an award he wouldn’t be invited to speak from the stage. In declining the award, Eldagsen says he wants to ‘drive debate’ about the use of artificial intelligence to create images. He amplified his onstage remarks with a statement on his website:

“I applied as a cheeky monkey, to find out if the competitions are prepared for AI images to enter,” Eldagsen wrote. “They are not.”

“How many of you knew or suspected that it was AI generated? Something about this doesn’t feel right, does it?” he added. “AI images and photography should not compete with each other in an award like this. They are different entities. AI is not photography. Therefore I will not accept the award.”

Neologisms

Eldagsen says we need a new word—and a new category—to make sure that we don’t get confused between images generated by photographers and images generated by software. Neologisms are always interesting to me because they are a marker of change, even when they don’t stick. Eldagsen’s preferred word is ‘promptography’:

“Promptography is done with prompts. Photography is done with light,” Eldagsen told the BBC. “I think it’s very important to differentiate these (two things) by terms, and then to have an open discussion about this in the photography world. Is the umbrella of photography large enough to say this (type of imagery) is part of it? Because the visual language is the same.”

I’m willing to take this at face value: there’s a long interview with him in Urbanautica about the importance of being able to trust that images are authentic. It also includes an intriguing selection of his AI-generated images.

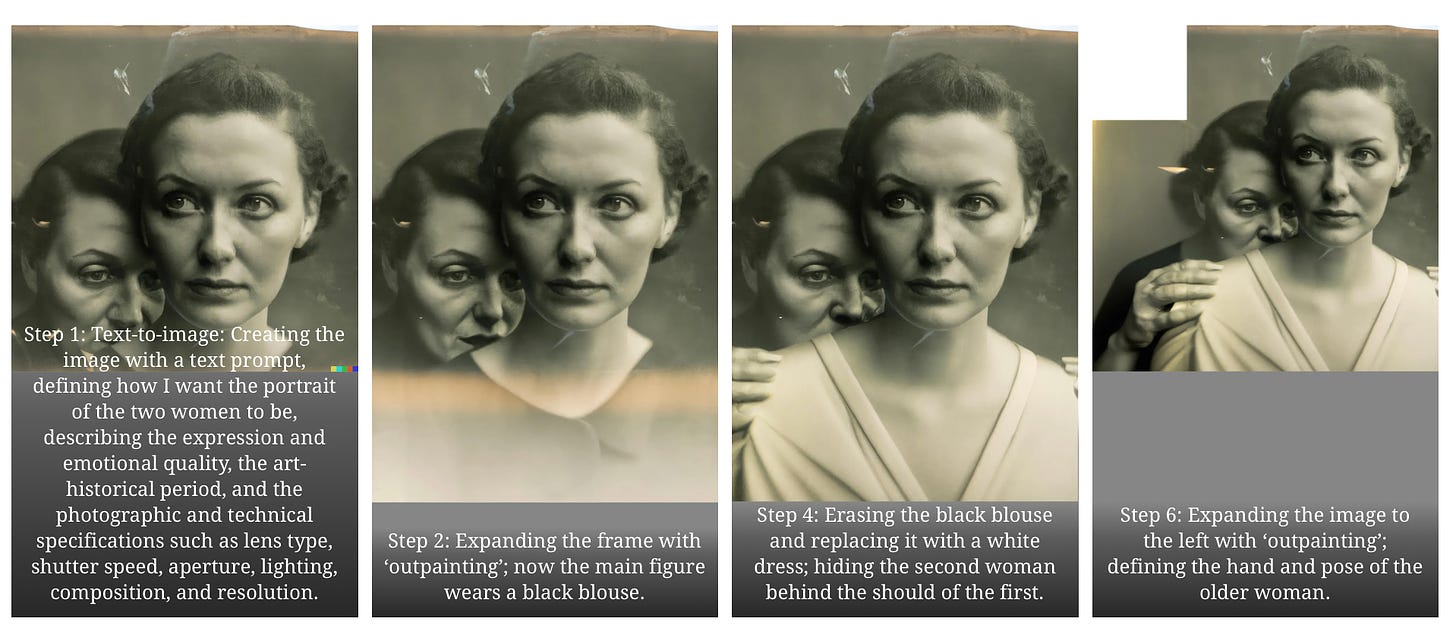

20 stages

All the same, there’s something about his position that doesn’t sit quite right for me. Because: what he’s doing is not simple. In one of the pieces published since the controversy (he was certainly right about declining the award ‘driving debate’), he describes what he did to make ‘The Electrician’. It’s not simple work. It involves 20 stages, of which eight were reproduced in the Australian photography magazine Talking Pictures.

And, of course, you can also see—AI or not—that this is a composed image, even while passing itself off as an early-ish 20th century collotype. Not everyone is going to be able to do this or get these results from a Large Language Model.

Although Eldagsen makes a strong assertion about the difference between photography and AI (light versus prompts) photography is already well past that stage. Any digital image is doing as much with technology adjustments and filters as it is with light, and a lot of contemporary work is then treated digitally as well.

‘A liberating blow’

And some of this argument also reminded me of the recurring controversy about hyper-realist painting, which is impossible without photography.

So it seems that this issue is maybe not so pressing when it comes to a ‘photograph’ such as ‘The Electrician’. As a piece of art, it’s not making any more claims on authenticity than any other portrait of two unknown women might do.

In fact, it might be quite liberating, as Eldagsen said to Talking Pictures:

What impact do you see AI imagery having on photography as an art practice?

One hundred and seventy years ago, Baudelaire pronounced the nascent medium of photography to be the “mortal enemy of painting, (…) refuge of all failed painters, the untalented and the lazy”. Today, AI artists are berated in much the same way by photographers. Back then, photographers took the likeness, the realistic representation, away from painters. It proved a liberating blow, the prerequisite for the development of modern painting.

Fake and real images

As far as I can see, Eldagsen is silent on the issue of the source imagery that a Large Language Model such as DALL E2 uses to construct images in response to his prompts. Obviously this is a live legal issue at the moment in the US courts. In one interview, though, he makes an interesting distinction between “the photographic”—the sense of the whole corpus of work on which an LLM has been trained—and “photography”.

But the more direct issue of distinguishing between fake and real images in day-to-day news—which Eldagsen raises as part of his critique—is a real issue. The Bellingcat founder and creative director Eliot Higgins made this point, satirically and graphically, in a widely shared tweet in March.

I think this is a different issue from whether a photography award needs to have a different category to assess images that are composed with the assistance of LLMs. That ship might already have sailed. Eliot Higgins clearly signalled that his images were digitally created. But people using LLMs with malicious intent to undermine our faith in what we see, and what we therefore understand about the world, are unlikely to pause to label their images as “promptographs”,

——

A version of this article is also published on my Just Two Things Newsletter.