I’ve been doing some project work and some training recently on horizon scanning, and this reminded me that I’ve been meaning to write up a talk I gave to a British government department called “Five things I’ve learned about scanning.”

One of the underlying principles of futures work is that change comes from the outside. First, it happens in the contextual environment, then it starts to influence the operating environment or the task environment, then, finally, it works through to the organisational environment. At risk of seeming ridiculously English, I use the analogy of a fried egg in a pan: the oil and the pan heats first, then the white of the egg, and then finally the yolk.*

One other note on Horizon Scanning, which also has a longer pedigree in the futures studies literature as ‘environmental scanning’. This alternative version emerged in Euopean government and policy circles in the 1990s, perhaps because policy-makers were concerned people would think that this foresight stuff was just about the environment and not take it seriously.

1. Structure matters

Yes, you do need some form of taxonomy, but not for the reasons sometimes suggested. The purpose of a taxonomy is to help you find things later, and also as a check when identifying scan hits for a project that you don’t have a blind spot in a particular area.

I tend to use STEEP (Social, Technological, Economic, Environmental, Political), but only if the P also covers legal and regulatory change. Or you can add the L and call it PESTLE. One of the taxonomic developments here, which emerged from Australian futures practice, is the addition of V, for values, which wrecks the acronym but improves the quality of the scan, given that values shift is one of the four sources of substantive generational change.

And strictly speaking, this shouldn’t be used as a taxonomy. If something seems to sit in—say—both Social and Politics, it may be better to tag it with both, so you don’t miss it when searching later.

But all the criticisms of STEEP are true. It’s flat, and when you do the analysis, the interesting stuff emerges when trends in different domains interact. Sometimes it’s better to use VERGE, developed by Richard Lum and Michele Bowman, with its more ethnographic headings: produce, consume, relate, connect, destroy, worldview.

2. Simplicity matters

I’ve seen horizon scans where every item is a briefing paper in its own right. I think this is unhelpful. Scanning is really only a useful as a platform for sense-making, and it’s better to be able to use the scan hits as a prompt to better understanding of the overall landscape, including your own blind spots. My rule of thumb is that you should be able to fit anything important about a scan hit on a piece of A5 paper. (That’s also a good size if you want to work with the cards physically in a workshop.)

The other reason for simplicity is in making sure that you don’t want to ask the researcher recording the scan hit for too much information, because they’ll forget what the different categories are and you’ll end up with dirty taxonomic data, which defeats the purpose.

At the end of the day, you’re only really asking three questions:

– Does this confirm something we already know?

– Does this change something we already know?

– Is this something new?

(The futurist Wendy Schultz adds some nuance to this last question: is this something new to us? — a blindspot, in other words. Or is it objectively new? — a novelty, in other words.)

3. Breadth matters

Futurists love S-curves, and one of the reasons they love them is that they sit under a lot of general systems patterns, even if the actual rate and patterns of change in actual systems is less smooth than the S-curve suggests.

The forecaster Theodore Modis, who made a good living from logistics curves, used to used a seasonal metaphor to describe S-curves: spring, when lots was going on, but much of it out of sight; summer, when new things burst through; autumn, when things are mature; and winter, when they decay and die.

It’s a reasonable analogy, and the point of thinking about it is to make sure that you’re researching the not so visible things happening in spring rather than seeing the more visible. Working with policy people I also use Graham Molitor’s three stage model of ‘Framing’, when new ideas are shaped (spring); ‘Advancing’, when they are promoted by advocacy organisations, but haven’t yet reached the mainstream (summer); and ‘Resolving’, when they hit the mainstream and reach formal policy or legal structures. (There’s a lot more here, but maybe for another day.)

4. Connection matters

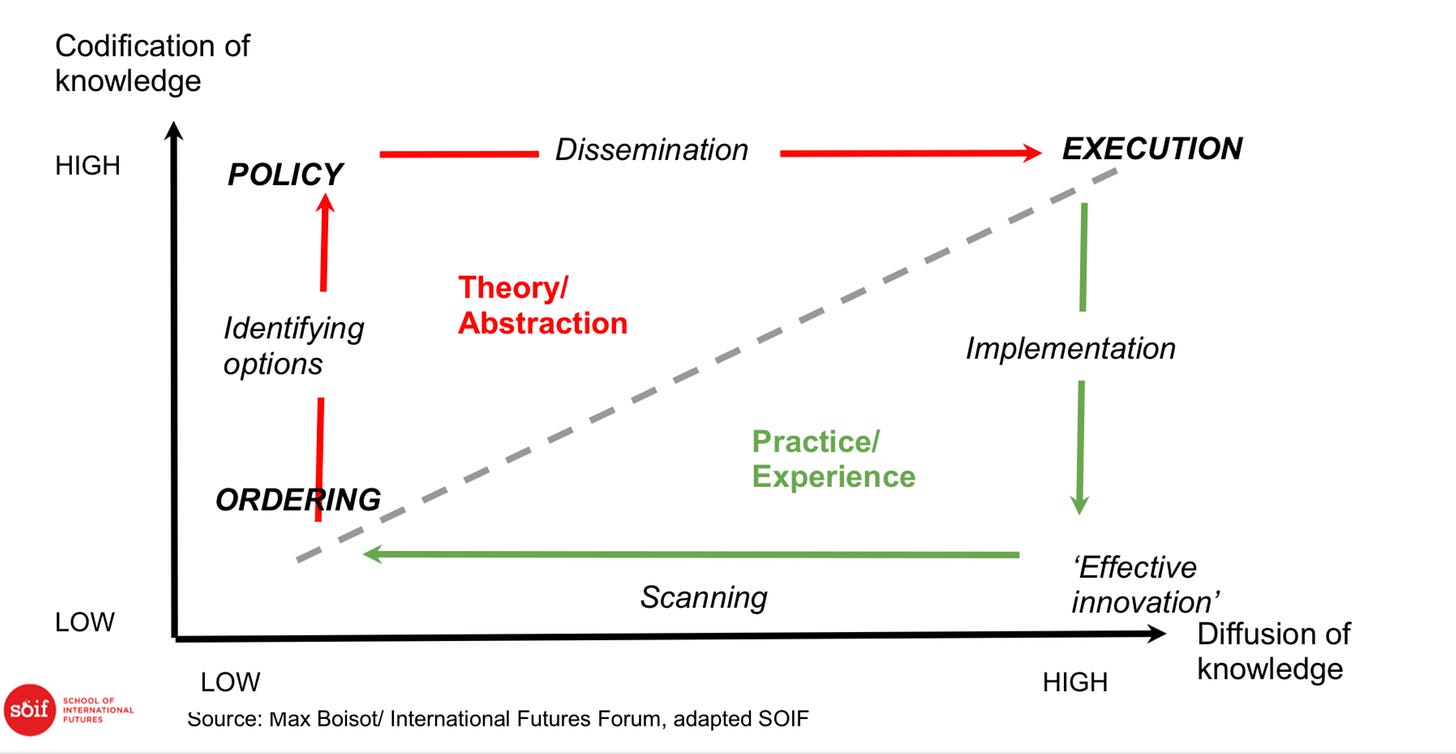

You need to be able to connect the output of the sense-making built on the scanning with the way that decisions get made. One of the things we’ve been doing at SOIF is to think about decision-making processes in organisations (which is frankly a bit of a gap in the literature) by drawing on some of work by the late Max Boisot on the ‘social learning cycle’ in organisations. (He developed a more complex version of this diagram later in his work).

Futures work effectively aligns with the left-hand side, where organisations codify their understanding of the world, and then interpret what it means.

5. Practice matters

Finally, the only way to get good at horizon scanning is to do it. And once you do it, a lot of the more mechanical aspects of scanning (taxonomy, S-curve and so on) become instinctive, as does noticing earlier signs of change—the so-called weak signals.

I suggested in the talk that there were some behaviours that helped with this:

– Be curious about change

– Embrace anomalies and outliers

– Hold exploratory views, but loosely

– Use tools that make you think differently

– Look for patterns rather than timescales.

An exercise I used to recommend was—when you were on a trip, say—to go into the station or airport bookstore and buy a magazine you’d never normally read (not necessarily a politics magazine) and understand their view of the world.

—

* I once used this analogy on a panel, and the person next me, who worked for a reasonably sized tech company, leaned over and said, ‘and if you’re sitting in the yolk you won’t notice what’s happening outside because that’s where all the nutrients are. Which extends the analogy perfectly.

———————————-

A version of this article was previously published on my Just Two Things Newsletter.

As usual insightful and readable. I would add one factor, which I call the “Prisoners of Language” problem. I used to ask people to discuss ” In the future, blind people will be able to drive cars”. I started around 2000 with this. The lesson was that the words blind, drive and car all could change in meaning on a realistic timescale. So, in horizon scanning on say ” the future of retailing” I’ve seen failed attempts to get to grip because ” Retail means Retail” type thinking.