Nicholas Eberstadt had an article in Foreign Affairs on what he calls “The age of depopulation”. (It seems to be outside of their paywall). It would be more accurate, of course, to call it “the coming age of depopulation—we’re not quite there yet. But when global population does decline, it will be the first time since the Black Death, 700 years ago, that global population has fallen.

Unlike the Black Death, however, this decline in population numbers will be driven entirely by social choices:

With birthrates plummeting, more and more societies are heading into an era of pervasive and indefinite depopulation, one that will eventually encompass the whole planet. What lies ahead is a world made up of shrinking and aging societies. Net mortality—when a society experiences more deaths than births—will likewise become the new norm.

This change is being driven by a deep-rooted collapse in fertility in most parts of the world. It’s impossible to overstate how big a change this is in human experience. We have no experience as a species of long-term depopulation. The cause is a declining desire to have children.

Fewer workers

In some countries—mostly those who are “at war with modernity” and have much rhetoric about the importance of family life—governments have tried to reverse this decline. They have had absolutely no success. We will end up, Eberhard suggests, with fewer workers and more demand for carers. But, he says, this is not necessarily a catastrophe: instead, it presents a difficult set of issues. But policymakers haven’t started thinking about the implications yet.

(Women on a bench. Free photo via Pexels.com)

I’m going to structure this in three parts: trends first; then implications; and then some possible responses.

The numbers first:

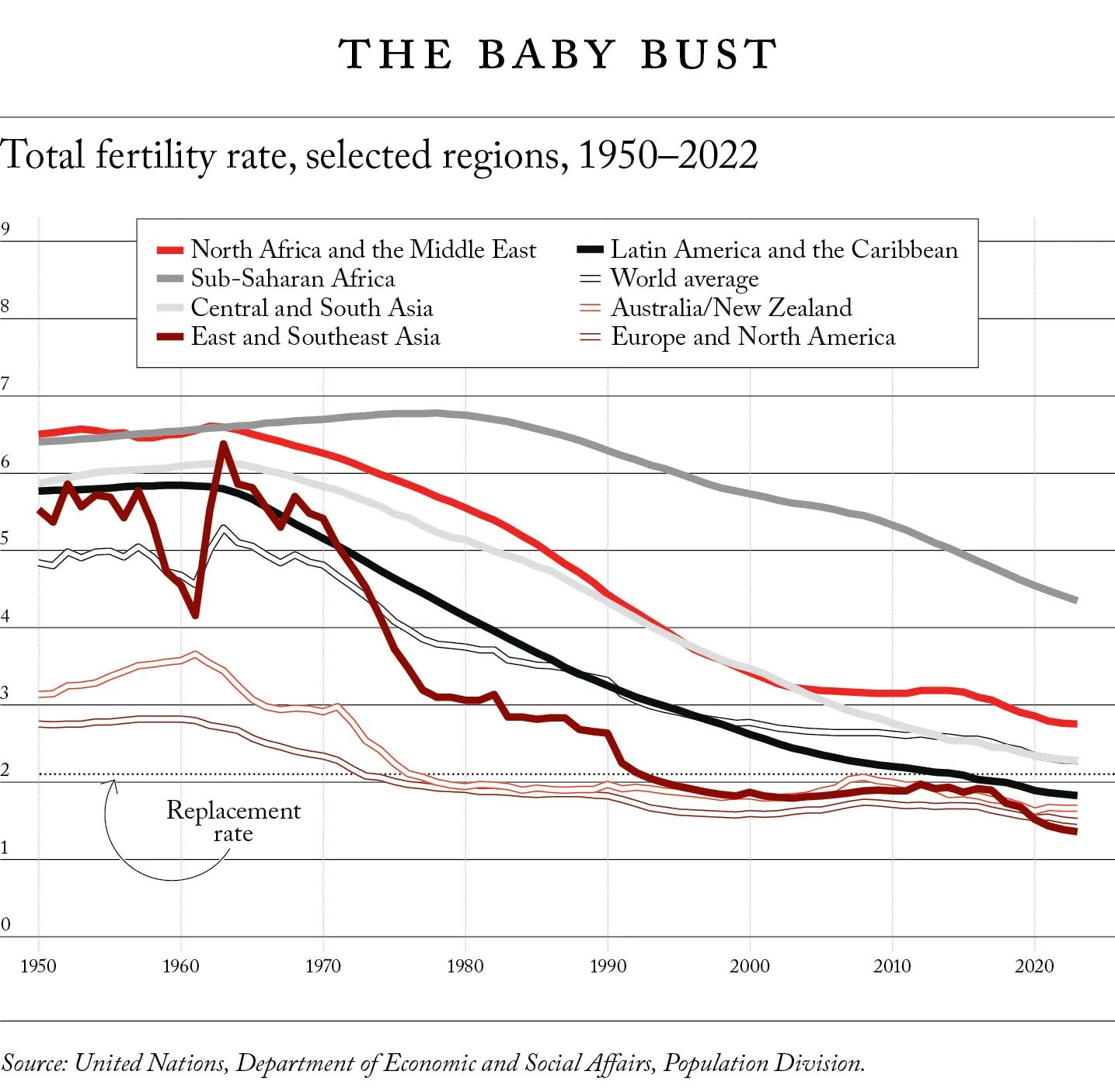

For over two generations, the world’s average childbearing levels have headed relentlessly downward, as one country after another joined in the decline. According to the UN Population Division, the total fertility rate for the planet was only half as high in 2015 as it was in 1965. By the UNPD’s reckoning, every country saw birthrates drop over that period.

Below replacement rate

By 2019, two-thirds of countries worldwide had fertility levels below the replacement rate (of 2.1 births per woman). Europe, obviously, has had low fertility rates for a while now. But in East Asia, every major country is depopulating:

By 2023, fertility levels were 40 percent below replacement in Japan, over 50 percent below replacement in China, almost 60 percent below replacement in Taiwan, and an astonishing 65 percent below replacement in South Korea.

In south-east Asia, the region as a whole is reckoned to have fallen below replacement levels in 2018; in south Asia, India, Nepal and Sri Lanka are all below, with Bangladesh about to join them. In India, in particular, the fall in urban fertility levels has been dramatic: in 2021, in Kolkatta, fertility levels fell to one birth per woman.[1]

The baby bust

There’s a similar story across Latin America and the Caribbean, where fertility levels in many countries are just a little above one; again, fertility levels in some cities are at or below one birth per woman.

And the same is true across North Africa and the Middle East.

Iran has been a sub-replacement society for about a quarter century. Tunisia has also dipped below replacement. In sub-replacement Turkey, Istanbul’s 2023 birthrate was just 1.2 babies per woman—lower than Berlin’s.

The only places where this story doesn’t hold up is in sub-Saharan Africa, where fertility rates are around 4.3 births per woman. But they are dropping quite fast.

(Source: United Nations via Foreign Affairs)

What women want

The reasons for this are still not clear. It used to be assumed that fertility levels fell as a result of material progress. But none of the traditional markers seem to hold. Countries with low income levels, high poverty levels, low education levels, and low rates of urbanisation are below replacement levels (Nepal and Myanmar, for example).

There’s a mass of sociological research on this, but the explanation seems like it might be simpler:

[I]n 1994, the economist Lant Pritchett discovered the most powerful national fertility predictor ever detected. That decisive factor turned out to be simple: what women want… Pritchett determined that there is an almost one-to-one correspondence around the world between national fertility levels and the number of babies women say they want to have.

Changing family formations

Why now? Eberhart offers some threads. There are changes in family formation—with people getting married later, or not at all, or choosing to live alone. These seem to be the case across different cultures and different value systems. The spread of global media may also be a factor. Conversely, religious belief is generally in decline. Eberhart mentions the growth of Inglehart’s ‘post-materialist’ values, associated with the Millennials and GenZ, without mentioning Inglehart:

[P]eople increasingly prize autonomy, self-actualization, and convenience. And children, for their many joys, are quintessentially inconvenient.

One casualty in all of this is the idea that humans are somehow hard-wired to replace themselves. Instead, with a nod to Rene Girard (again without mentioning him) Eberhard says this might be a win for mimetic theory:

[I]mitation can drive decisions, stressing the role of volition and social learning in human arrangements. Many women (and men) may be less keen to have children because so many others are having fewer children.

Deaths over births

We don’t quite know yet when the global population will turn. This is a complex system. It really depends on how quickly fertility levels fall in sub-Saharan Africa, so it could be any time between the 2050s and the 2080s. But some projections suggest that by 2050 deaths will exceed births in two-thirds of the world’s countries.

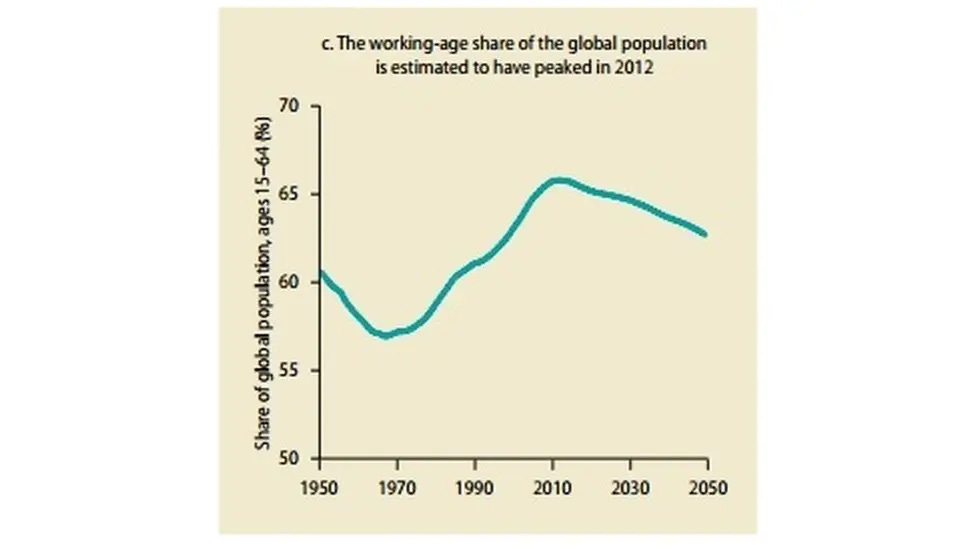

Before that, we’ll see workforces shrink as a result of sub-replacement fertility levels.

By 2050, two-thirds of people around the world could see working-age populations (people between the ages of 20 and 64) diminish in their countries—a trend that stands to constrain economic potential in those countries in the absence of innovative adjustments and countermeasures.

I’m a bit puzzled by this data point, because I had thought that the peak in working age population globally had happened already. Duncan Weldon, then the economics correspondent of BBC Newsnight wrote a piece based on a World Bank report in 2015:

The share of the global population of working age (defined as 15 to 64) is forecast to fall. The working-age share rose strongly for the 40 years to 2012 and the fact it is now falling (a fall driven by both rising longevity and the past impact of a falling birth rate) could have a major impact on the shape of the global economy.

(Source: Global Monitoring Report, via BBC)

No matter, perhaps. The point is that we are headed for ageing populations almost everywhere. Perhaps we are already there: the average age has passed 40 in increasing numbers of countries. And we haven’t been here before as a species. We are used to younger societies.

A policy problem

So, to recap: Fertility levels are falling everywhere, and have reached below replacement levels in large parts of the world. In the article, Eberstadt says it’s definitely a policy problem, but it may not be a catastrophic one.

I think he might be whistling in the dark to keep himself cheerful, but I’ll come back to that later on.

Some of the projections for societies such as South Korea that are at the leading age of falling fertility levels, and by extension, the development of ageing, are stark to the point of being dramatic—indeed, Eberhart uses the phrase “mind-bending”:

Current projections have suggested that South Korea will mark three deaths for every birth by 2050. In some UNPD projections, the median age in South Korea will approach 60… South Korea will have just a fifth as many babies in 2050 as it did in 1961. It will have barely 1.2 working-age people for every senior citizen. Should South Korea’s current fertility trends persist, the country’s population will continue to decline by over three percent per year—crashing by 95 percent over the course of a century.

Threatening prosperity

It’s a useful reminder that exponential trends can head down as well as up. But Eberhart’s point is that South Korea is effectively the “frontier” country for these trends. Where it leads, the rest of us will follow.

The consequences are not good.

The pervasive graying of the population and protracted population decline will hobble economic growth and cripple social welfare systems in rich countries, threatening their very prospects for continued prosperity. Without sweeping changes in incentive structures, life-cycle earning and consumption patterns, and government policies for taxation and social expenditures, dwindling workforces, reduced savings and investment, unsustainable social outlays, and budget deficits are all in the cards for today’s developed countries.

And not just in developed countries. Until now, the countries that have grayed the soonest have been richer countries with reasonable social safety nets in place. But one of the consequences of falling fertility rates in more places is that poorer countries will also need to adapt, with less economic cushion to do so:

The poor, elderly countries of the future may find themselves under great pressure to build welfare states before they can actually fund them. But income levels are likely to be decidedly lower in 2050 for many Asian, Latin American, Middle Eastern, and North African countries than they were in Western countries at the same stage of population graying.

Over-80s

The problem—as Eberhart positions it—is that 60- and 70-somethings may well be active, even economically active, the same is not true for over-80s. This group is the world’s fastest growing cohort (albeit from a fairly small base) and by 2050 in some countries there will be larger numbers of over-80s than children.

But the same changes in family structure that have contributed to this demographic shift also mean that is harder for families to help cope with it:

As familial units grow smaller and more atomized, fewer people get married, and high levels of voluntary childlessness take hold in country after country. As a result, families and their branches become ever less able to bear weight—even as the demands that might be placed on them steadily rise.

Eberhart doesn’t really have a solution to this. He thinks that technology might eventually be able to help, but not soon. Carers might come from non-family members. He’s not a fan of the state doing the work, because he thinks it is an expensive substitute for the family, “and not a very good one”.

Oh, but technology

However, he is confident, I’d say over-confident, that the same trends that have enabled growing prosperity over the past two or three generations might come to our rescue.

The essence of modern economic development is the continuing augmentation of human potential and a propitious business climate, framed by policies and institutions that help unlock the value in human beings… Improvements in health, education, and science and technology are fuel for the motor generating material advances. Irrespective of demographic aging and shrinking, societies can still benefit from progress across the board in these areas.

Even with this level of optimism, he says that the transition to an ageing world will be disruptive. The social care systems we have are basically designed to benefit from growing populations, which is why they have worked over a century or so in which global population has grown sharply:

In depopulating societies, today’s “pay-as-you-go” social programs for national pension and old-age health care will fail as the working population shrinks and the number of elderly claimants balloons.

Climate costs

He thinks that the societies that succeed will be more open—more open to innovation, more open to migrants. I can see the second point, although this is most likely to make the ageing crisis in countries with less resources more acute. This is a beggar-your neigbour world. I can see the theory about the first point, but one of the things we know about it is that the rate of innovation is slowing down.

Eberhart also seems blind to the likely effects of climate change in this future world, which is likely to impose much greater costs on states. It is also likely to have worse effects on older citizens—extreme heat, notoriously, is hard for the very old and the very young to deal with.

This is Foreign Affairs writing, and inevitably he has a poke at the geopolitics. Most of the young people in this future world will be African, but this will not lead, he says, to “an African century”, since skills and investment levels remain patchy on the continent. (Even though in this world young workers are at a premium).

Skills gaps

India’s population profile means that it will be “a leading power” by 2050. But again, although some of its top level skills are world class,

ordinary Indians receive poor education. A shocking seven out of eight young people in India today lack even basic skills—a consequence of both low enrollment and the generally poor quality of the primary and secondary schools available to those lucky enough to get schooling.

China—ageing far more quickly—has a far more skilled population in comparison.

And although the United States has sub-replacement fertility levels, it has a younger population than many places because of relatively high immigration levels, and will, says Eberhart, prosper, at least relatively, if it continues with its relatively open immigration policies.

The other big question is how countries react to this crisis of ageing.

Nothing guarantees that societies will successfully navigate the turbulence caused by depopulation… To achieve economic and social advances despite depopulation will require substantial reforms in government institutions, the corporate sector, social organizations, and personal norms and behavior.

Stark economics

In practice we have already seen some of what happens in depopulating societies, since regional depopulation is already associated with the rise of far right political parties, and people who have less optimistic views of the future are also more likely to turn to the right. We don’t know yet whether this effect is a cohort effect or not—older voters in declining areas may also hold more traditional values, whereas the 60-70 year olds in 2050 are Millennials, and may have different values. (Eberhart doesn’t discuss this).

But the economics are stark: most of the world’s GDP is produced in countries that will be depopulating in 2050:

The nightmare scenario would be a zone of important but depopulating economies, accounting for much of the world’s output, frozen into perpetual sclerosis or decline by pessimism, anxiety, and resistance to reform.

—

[1] This seems to the result of the combinaation of increasing women’s educational attainment with shocking levels of misogyny and male privilege.

—

A version of this article was also published on my Just Two Things Newsletter.