Over the holiday break Exponential View republished a piece by Azeen Azhar it had run earlier in the year on GLP-1 drugs. (In other words, drugs like Ozempic.) First time around, I’d noticed the headline, but not had time to get into the detail. But seeing it during the holiday meant I was able to give it more consideration.

The Exponential View headline story is this:

I reckon that they will be the most impactful technology in the US over the next two years, with more meaningful and measurable impacts than either artificial intelligence or renewable technologies.

So if that’s right, they’re quite a big deal. The Exponential View piece is behind a paywall (I have a subscription) but Azeem Azhar links to substantive content that is free-to-air that goes into more detail on the mechanics of the drugs.

Diabetes patients

Backing up a bit: GLP-1s (more formally, ‘GLP-1 receptor agonists’) were introduced into the market by the large pharma companies initially as a way to help patients with Type 2 Diabetes, but have since become a way to help patients who are overweight to manage their weight down.

Once of the consequences of this, apparently, is that diabetes patients, who really need the drugs, have difficulty ensuring their supply.

All the same, patients can’t get enough of them, looking at the US data:

GLP-1 prescriptions have quadrupled in the US over the last three years. Recent data shows that nearly 5% of patients receiving any prescription are now prescribed a GLP-1 RA. By some estimates, there were nine million prescriptions for GLP-1s at the end of 2023, which means that 3% of Americans are already on these drugs.

Market cap

The potential market in American alone is much larger, given that 100 million Americans suffer from obesity.

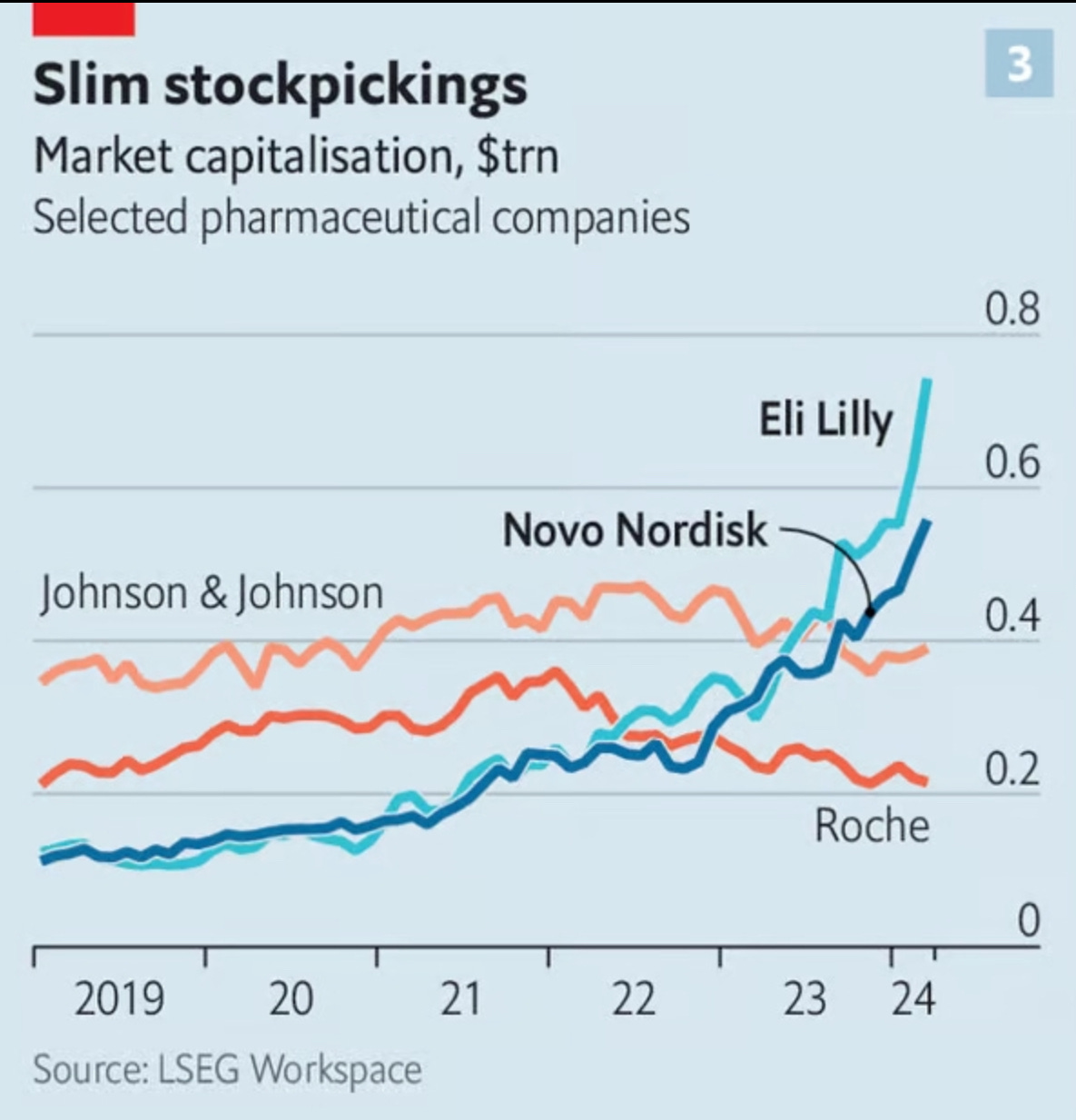

The impact on the pharma companies who make these drugs has been dramatic. Exponential View shared a chart from the Economist that showed the growth in the share price of Eli Lilly, which makes Mounjaro, and Nono Nordisk, which makes Ozempic. Eli Lilly became the most valuable pharmaceutical company in the world in 2023 off the back of its GLP-1 orders, and Novo Nordisk the most valuable company in Europe.

(Source: The Economist/ LSEG Workspace, via Exponential View)

Extending duration

GLP-1s are found naturally in the human body, but are ingested very quickly. What the pharma companies have done is combine it with other chemicals to extend the duration of their effects, as the psychiatrist Scott Alexander notes:

By playing around with its structure, Big Pharma was eventually able to create liraglutide (twelve hours), semaglutide (one week), and cafraglutide (one month).

So we should step back and ask what is going on here. Are GLP-1s a ‘wonder drug’ or a fad? Scott Alexander has looked into this in some detail, and I’ll try to summarise his argument.

He starts by noting the widespread range of things that they seem to be able to treat:

GLP-1 receptor agonist medications like Ozempic are already FDA-approved to treat diabetes and obesity. But an increasing body of research finds they’re also effective against stroke, heart disease, kidney disease, Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, alcoholism, and drug addiction.

Addictive behaviours

Of course, that makes them sound like a wonder drug, rather than a fad. Scott Alexander runs through the reasonably well known explanations of why they work for diabetes, and then points out that the weight loss effects were unexpected. We noticed that they were having that effect before we understood why.

What’s more interesting is that GLP-1s are also associated with reductions in addictive behaviours. Although this is usually reported anecdotally, a more robust meta-study in Brain Science which used a ‘mixed methods’ approach to analyse social media reports about ‘Substance use, compulsive behavior, and libido’ also found this to be the case. From the abstract:

In total, 29.75% of alcohol-related; 22.22% of caffeine-related; and 23.08% of nicotine-related comments clearly stated a cessation of the intake of these substances following the start of GLP-1 RAs prescription… Regarding behavioral addictions, 21.35% of comments reported a compulsive shopping interruption, whilst the sexual drive/libido elements reportedly increased in several users.

Receptors

As Scott Alexander notes, there is no such a thing as a “miracle drug”. Drugs work by acting on receptors in the body or the brain:

There are two plausible places GLP-1 drugs could lower weight: the body or the brain. In the body, they could change stomach contraction rate, hormone production, etc. In the brain, they could control the mental sensation of hunger. To separate these two effects, scientists bred rats that only had GLP-1 receptors in one place or the other. The results were unequivocal: Ozempic and its relatives work in the brain.

(Ozempic. Photo: Chemist4U/flickr. CC BY-SA 2.0)

There are reasons why this is surprising, and the mechanisms are definitely complex (read Scott Alexander for all of this), but at a headline level GLP-1s seem to—through different mechanisms—suppress hunger and also influences the (dopamine-based) rewards system in such a way that it suppresses addiction:

Broad-spectrum dampening of the reward system is a terrible fate… But the existence of silver bullet anti-addiction medications—Ozempic isn’t the only one, naltrexone seems to treat a whole host of different drug and behavioral addictions—suggests there’s also a sort of narrow-spectrum dampening, one which affects addictions and nothing else.

Economic drag

Let’s assume, therefore, that these effects are real and that they sustain, and look at the wider implications of this. Exponential View quotes Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley on GDP and labour market participation, which tells you more about the thinness of public policy discussion than anything else.

But they both point to the size of the economic drag of America’s obesity epidemic:

Morgan Stanley reckons the negative macroeconomic impact of obesity is “3.6% of U.S. gross domestic product with a potential $1.24 trillion in indirect costs from lost productivity”…. Goldman Sachs separately reckons the effect of tackling the obesity epidemic through GLP-1 agonists could vary between adding 0.1 to 1.1% to GDP.

Of course, if the effects in reducing addiction are real, then you might see this offset by lower consumption. Walmart say that those using GLP-1 drugs buy less food, and are less likely to eat out or order food for home delivery.

Of course, this isn’t the real effect. The real effect, if they sustain, is about wellbeing: first to improve the physical quality of life of users, so they are able to participate more fully in social and cultural life as well as economic life. And second, in reducing addictive behaviour, it improves the psychological quality of life as well.

Bailing out Big Food

Of course, this also comes down to cost. A 30-day supply of Ozempic costs $900 in the US, which is five times as much as in Japan and 10 times as much as in Britain or Australia.

But it’s also worth stepping back and looking at the bigger picture. I have written here recently about both the external costs of the food market—$10 trillion a year globally according to the Food and Agriculture Organization—and the addictive nature of Ultra-Processed Foods.

So this is also a story about late capitalism. Rather than dealing with the causes of the obesity epidemic in the Big Food system, public and private health systems end up paying billions, or more, to Big Pharma, to deal with the consequences.

—

A version of this article was also published on my Just Two Things Newsletter.