I’ve been digesting tariff chat for the past few days, like everyone is, and trying to make sense of the political economy of it. ‘Make sense’ as in trying to piece together the MAGA mindset and then think it through, beyond the economics of it. And just as I had a piece drafted, the Administration turned around and ‘paused’—up to a point—most of the tariffs it had imposed.

If you do want a straight review on how tariffs work, and don’t work, Noah Smith has a good explainer. Kyla Scanlon also does a Q&A (thanks to The Browser for this link).

But before I get to the heavier end of the content, let’s turn to the Bloomberg newsletter, in which Jessica Karl treads smartly but lightly over what’s happening in the world. On this occasion by quoting a Bloomberg editor on GenZ slang:

That also seems to be how the world has responded to the initial announcement, perhaps because the randomness of the numbers created suspicions that the White House policy was based on asking an AI [1]. One of the metaphors about Trump that’s been used in the past that seems to have stuck in his second term is of the gangster—even in the pages of the Financial Times. But gangsterism still needs a credible threat if it’s going to work. For this reason, I also liked the article—I’ve mislaid the link—that pointed me to The Sopranos as a metaphor for what was going on:

There’s a lot going on here, so I’m going to try to parse it out. I’m going to start with the rationale, and then try to unpick some of the political economy here.

The rationale

Trump, in general is obsessed with material goods, and not so much with services. So he obsesses about trade deficits, and doesn’t notice the large service surplus that funds them. (Or that America, pretty much uniquely, exports dollars for use as a reserve currency by other countries, which effectively also subsidises the US.)

Hence his notion that every other country in the world is “ripping off America.”

Noah Smith suggests that this is because his economic advisers have misunderstood, deliberately or not, the basic equation for Gross Domestic Product [GDP] that people learn the first time they do economics [2]:

The formula is Y=C+I+G+(X−M), where C is consumption, I is investment, G is government spending, X is exports, and M is imports.

So it looks obvious: if you get rid of that -M, you’re that much richer. But as Smith reminds us, this is just a way of tidying up the data, because consumption, investment, even government spending, all include imports, but they’re harder to measure there: much easier just to count the imports as they come in and deduct them from the total [3].

Complex supply chains

There’s a second assumption that sits inside the White House worldview: that if all of those imports stop coming in, then American companies will start making those goods themselves. Well, the best answer to this is: it depends. In a world of complicated goods and complex supply chains, it is much less likely than it used to be. In the Financial Times, after the initial round of announcements, their veteran economics writer Martin Wolf reckoned that the shape of trade in goods with America would mostly remain the same even after the punitive levels of tariffs announced last week, but there would just be less of it.

But even if American companies filled the gap, there would be a delay. It takes time to build capacity, skills, products, markets, and so on.

The other thing here is that in terms of the overall American economy, manufacturing production—which is what all of this is about—is small beer these days. It makes up 8% of the US economy. Even if every single one of the manufactured goods that are currently imported into America was made in the United States instead, that figure would climb to… 9%.

What’s going on

So this is a lot of chaos, even with the “pause” announced on Wednesday, for a tiny and possibly hypothetical gain.[4] It’s not exactly smart policy. You’re left with several choices about what’s going on.

The first is that the White House genuinely doesn’t have a clue: Trump is obsessed with tariffs, and always has been, and his cast of MAGA sidekicks see it as their job to go along with what the President wants. It is a tiny talent pool, after all. We’ll come back to the ideological point in a moment.

The second is a reminder that we are dealing with a man who told an aide during his first term that he needed to “win” something every day. “Win” as in having stories about him that put him in the spotlight and made him look good. The attention is the message. This makes for lots of tactical noise and no strategy.

Share tips

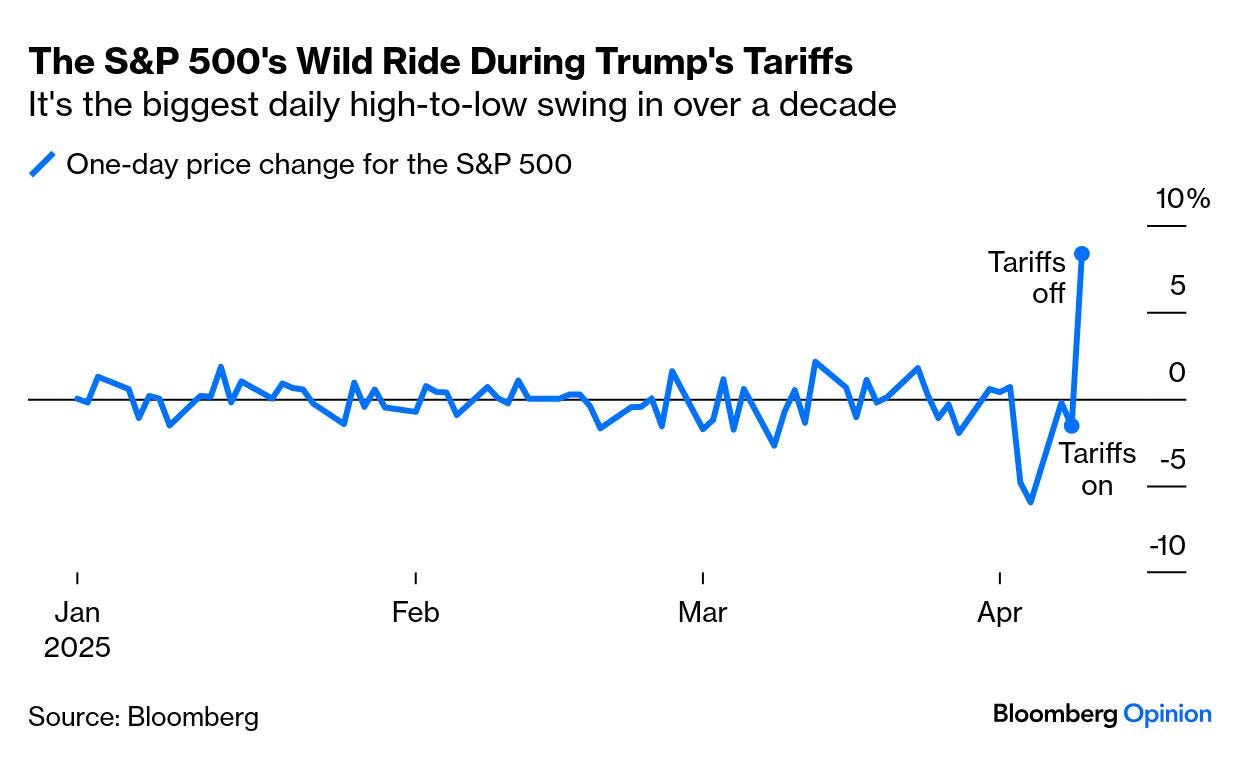

Then there’s the thought that it might all have just been an insider trading play. The stock markets headed down, fast, in response to the original tariff announcements. They didn’t recover. When the “pause” announcement was made, they picked up again quite quickly.

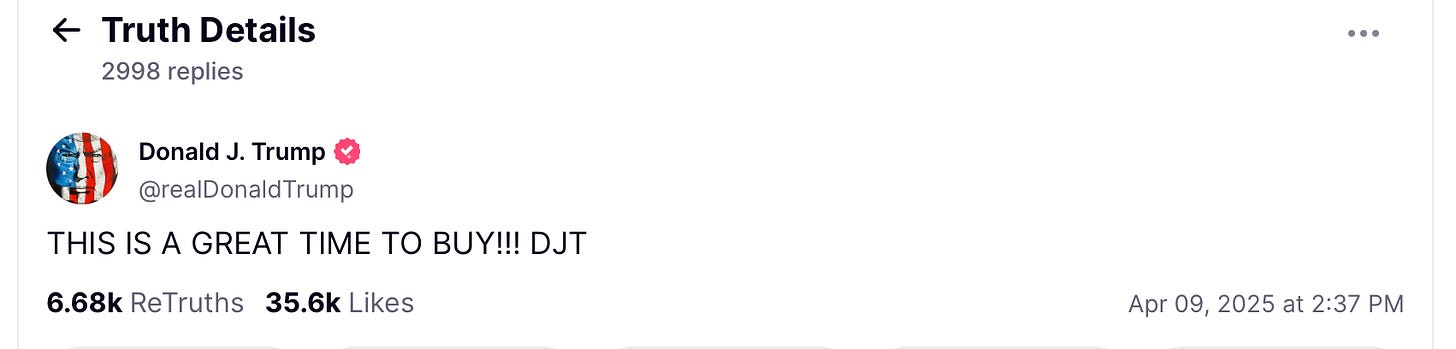

So someone who sold at the right time and bought at the right time would have done pretty well. Of course, there used to be rules to stop politicians doing that in the US, but one of the first things the Trump administration did was to remove them. Anti-corruption measures are for the little people. And here’s Donald issuing share tips just before the “pause” announcement on his Truth Social platform:

It’s pretty evident that some of this happened, but I don’t think it is the reason it happened.

Income tax

What seems to sit behind Trump’s obsession with tariffs is that he hates income tax. He said as much in his so-called “Liberation Day” pronouncement, as Heather Cox Richardson noted on her currently unmissable blog:

“You know, our country was the strongest, believe it or not, from 1870 to 1913. You know why? It was all tariff based. We had no income tax.”

Of course, this is a total misreading of history:

[T]he Panics of 1873 and 1893 devastated the economy, few Americans at the time thought the Gilded Age was a golden age… Congress passed the 1913 Revenue Act imposing income taxes to shift the cost of supporting the government from ordinary Americans, especially the women who by then made up a significant portion of household consumers, to men of wealth.

Sales tax

So in brief, tariffs, then as now, fell disproportionately—in effects as a sales tax—on working-class Americans. Income taxes did not. The logic here is that same logic that ensures that Trump administrations are willing to go into debt to give tax cuts to the wealthy.

The other missing piece in this is that the cost of government was tiny in the later part of the 19th century, and manufacturing and resources was a much larger part of the economy, and not just in America.

But at least this is of a piece with other parts of MAGA thinking: the hatred of Woodrow Wilson as the architect of “totalitarian government intervention”, which has only been extended over the course of the century since, and the assaults on the administrative state.

Giveaways

This point about income tax was underscored by the Democrat Senator Elizabeth Warren in an article by John Cassidy in The New Yorker:

In our conversation, Warren underscored that the Republican desire for tax cuts seems to know no bounds. “Even in the middle of this chaos, they are moving forward on a bill that has trillions of dollars in giveaways to corporations and billionaires,

But leaving aside all of the other issues around tariffs, even if the imposition of tariffs worked, the revenues would be a tiny fraction of the funding needed by a modern government.

Markets

It’s seems clear now that the “pause” on Wednesday night was prompted by the fact people were selling American Treasury bonds as well as stocks. It’s not supposed to work like this—normally investors turn to Treasuries as a safe haven for their money when stock markets are volatile. Without going into the technicalities of this, when investors buy bonds, and their price goes up, it means that the US government is paying less to service its loans and debts.

Because investors were selling rather than buying, the cost of servicing government debt was going up rather than down. There’s been a a couple of explanations for this, and both might be true. The first is that the market crash was squeezing some financial sector players, risking a financial crisis. John Cassidy, again, on Thursday:

Lawrence Summers, a former Treasury Secretary, warned online that “developments in the last 24 hours suggest we may be headed for serious financial crisis wholly induced by US government tariff policy.”

Selling bonds

The second is that countries holding US Treasury bonds, who were on the receiving end of tariffs, sold their bonds. China, almost certainly; and also a group of traditional American allies co-ordinated by Mark Carney, once the Governor of the Bank of England and now the Prime Minister of Canada. Canada had been building up its holdings of US bonds against this moment.

According to Dean Blundell’s Substack:

Carney [held] closed-door meetings with the EU’s heavy hitters—Germany, France, the Netherlands. Japan was in the room too, listening closely. The pitch was simple: if Trump went too far with tariffs, Canada… would start offloading those Treasury bonds. Not a fire sale—nothing so crude. A slow, steady bleed.

There’s lots more here, but there’s a bigger point. There’s no such thing as a “free market”. All markets are underpinned by some combination of laws, regulations, contracts, social institutions and social relationships. And one of the things that seems to have spooked investors—apart from the randomness of the tariff announcements and the strange calculations that sat behind them—is the lawlessness of the current Administration.

Risk premium

As Katie Martin said in the (paywalled) Financial Times on Friday:

[A] risk premium will sit on US assets that was not there before… Its stocks carry political risk for the first time. Its bonds no longer act like they are truly risk-free. The dollar is not acting like a magnet during periods of stress.

Given Trump’s personal business history, I’ve also seen it suggested that investors may have also feared that the Administration might just default on some its debts.

China

The “pause” on tariffs didn’t extend to China. Gangsters need to find a way to save face when they back down. But doubling down on China seems like it might be a mistake. If any country in the world understands the intricacies of global supply chains, it’s China.

China responded to the tariff announcement by announcing new licensing arrangements for exports of a series of critical minerals—samarium, gadolinium, terbium, dysprosium, lutetium, scandium, and yttrium. Michael Barnard described them as

the elements that don’t make headlines but without which your electric car doesn’t run, your fighter jet doesn’t fly, and your solar panels go from clean energy marvels to overpriced roofing tiles.

Precision

In other words, they target, very specifically, defence, advanced manufacturing, and cleantech. Barnard goes into some detail on each of these in the piece. It’s not a ban. It’s just paperwork. But the person who made the decision knew what they were doing:

They’re chosen with the precision of someone who’s read U.S. product spec sheets and defense procurement orders… They didn’t need to say no. They just needed to say “maybe later” to the right set of paperwork.

It’s more sophisticated than that, because the licenses ensure that China will learn a lot about who is using these materials, and for what reasons. Eventually the US might be able to source some of this from elsewhere, but not quickly. In some of the commentary I’ve seen, it’s suggested that this isn’t even a “retaliation” by China. It’s more like an opening shot across the bows, by way of a gentle reminder.

Footnotes —

1 This is explained by The Verge. Alex Tabarrok thinks they could have used better prompts.

2 The famous Upton Sinclair quote comes to mind here: “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it.”

3 If this seems technical, imagine a barren island with a lighthouse on it. The island produces nothing, and everything the lighthouse keeper needs has to be shipped in by boat. The island’s GDP is zero: all of the lighthouse keeper’s Consumption is covered by Imports.

4 The “pause” still leaves 10% tariffs on American imports, more on some categories of goods, and a hike on the tariffs on China. The decision seemed to have been made so quickly that the White House wasn’t able to give clear answers on the detail. But American tariff levels, even with the “pause” are at their highest levels for a century.

—

This is an updated version of an article that was also published on my Just Two Things Newsletter.