I’m a member of the Agri-Foods for Net Zero network, and it runs a good series of knowledge sharing events. (I’ve written about AFNZ here before). Last month it invited one of Britain’s leading systems academics, Gerald Midgley, to do an introductory talk on using systems thinking to explore complex problems.

All of the images here are courtesy of Gerald Midgley, who generously shared his slides after his talk. AFNZ has also shared a video of the talk online.

The questions he addressed were:

- What are highly complex problems?

- What is systems thinking?

- Different systems approaches for different purposes

Highly complex problems involve many interlinked problems, involving multiple agencies, with different views on the problems and the potential solutions. There’s conflict about preferred outcomes, preferred means to those outcomes, and power relations that make change difficult. There’s also uncertainty about the possible effects of action.

Complex problems

The focus of the talk was on using systems to address complex problems in the context of policy and management ideas. Although he has been working in this area for decades, he thought there had been a tipping point in 2017, when the United Nations, World Heath Organization and the OECD called for a systems approach to join up the sustainable development goals.

There are, he said, three dimensions to thinking. These are: in your head; thinking with other people (which is what we use language for); and feedback with the material world. He also observed that thinking and emotion are part of one cognitive system. Every thought is accompanied by a feeling that is accompanied by an emotion.

Our thinking is also fundamentally anticipatory—what we see around us is shaped by what we think is going to happen, and this is based on our past experiences. This is the most efficient way to think, but it also leads to partial interpretations of the world.

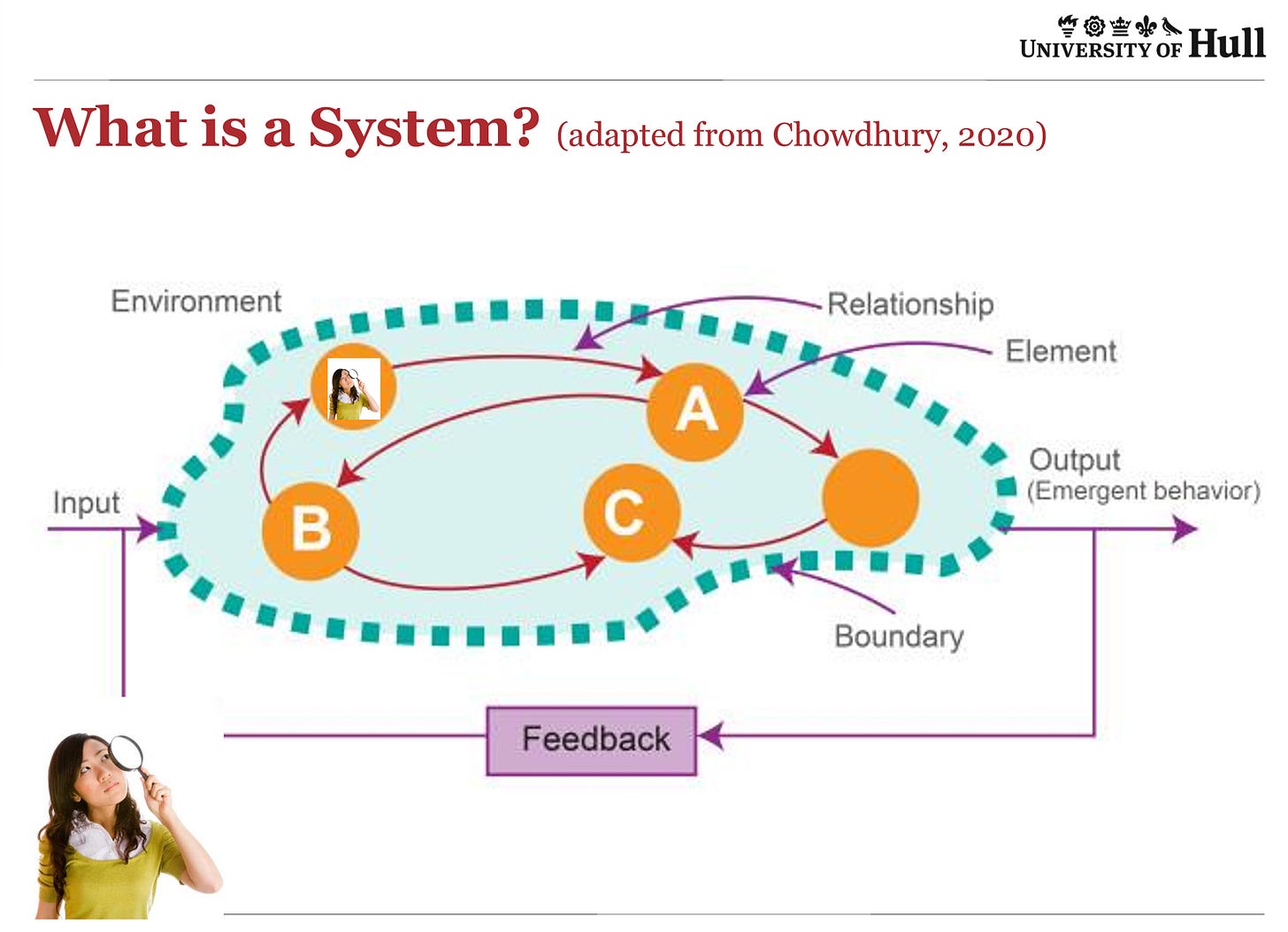

(Source: Gerald Midgeley)

Inside, not outside

A system has inputs, outputs, boundaries, and relationships between the elements. A system also has feedback. We can say what is inside and outside of the system, but boundaries are always seen from the particular perspectives of people in the system. And: we always see a system from its inside despite the image in the picture of the woman looking at the system from outside. She is there as a pedagogical point about the impossibility of doing this.

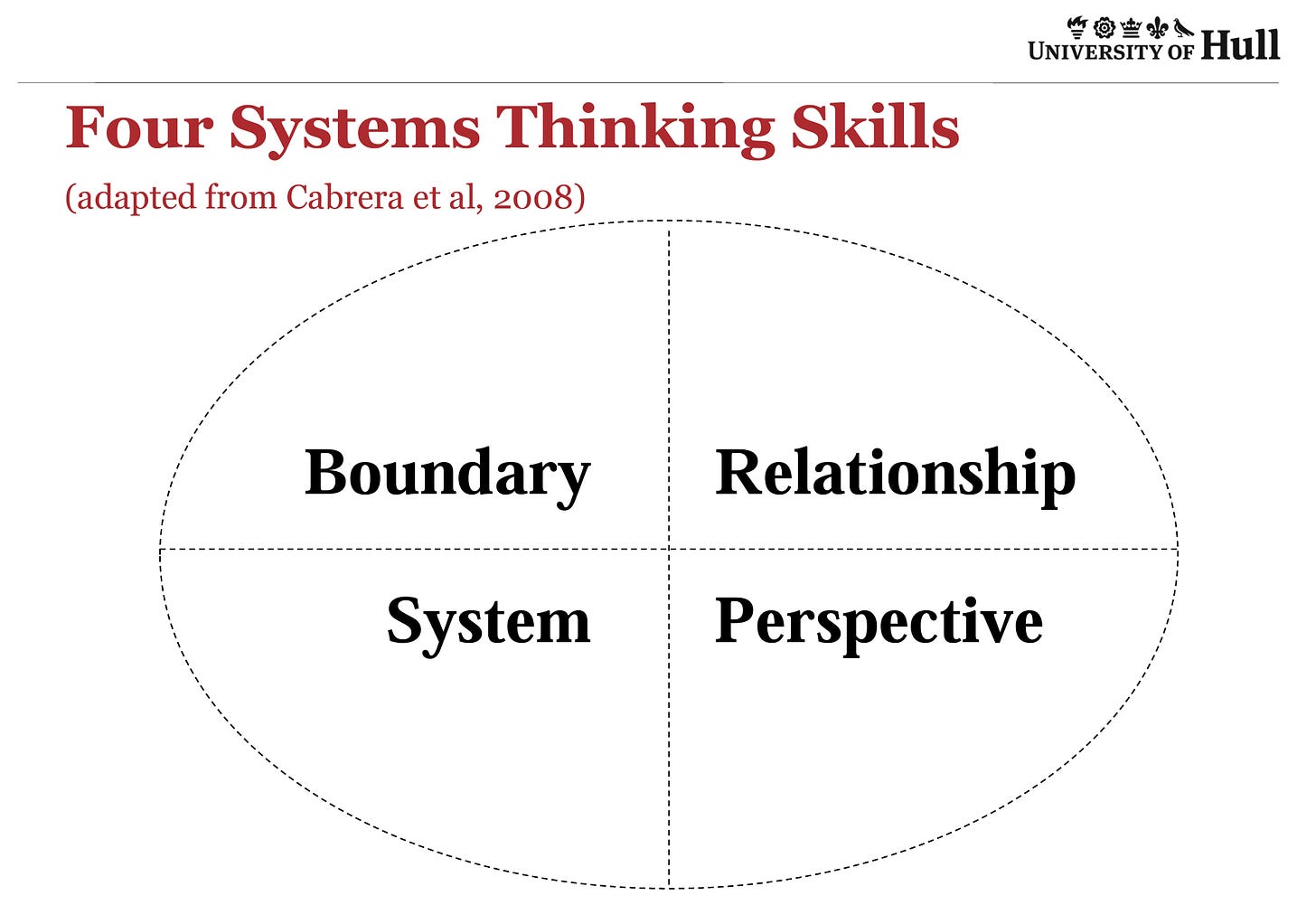

The talk was structured around a framework of systems thinkings skills adapted from the work of Derek and Laura Cabrera. Each of the four was used to introduce a different approach.

(Source: Gerald Midgeley)

The Cabrera framework helps you to map different approaches. Each element tends to focus on different parts of the system. And Midgley used each one of them to introduce a different element of systems thinking.

1. Boundary critique

Boundaries are about inclusion and exclusion. Those inside have views on “what could or should be done” — which often constrains views on what can be done. Conflicts over boundary judgments are common, but they also point you to areas of common concern.

Midgley gave an example of this from some work one of his students had done in Nigeria over waste reduction. There was conflict with a food production company over the dumping of animal effluent, exacerbated by an unreliable energy supply. The community had got the government involved, which was fining the company for breaching waste regulations.

As a result of this conflict the company had halted expansion plans, to limit the scope for further disputes. The systems research drew a bigger boundary around this. The animal waste was reimagined as a source for biogas, which in turn ended the energy issues. A viable biogas plant needed more animal waste, and the company found that there was a market for much more production, creating jobs in the community and increasing its profitability.

2. Complex causal relationships

Midgley shared a systems dynamics diagram at this point, pointing to the work of Jay Forrester. Of course, they are hard to read, but they are not designed as communications devices: that’s not the point of them. They are there, in effect, as boundary objects (my phrase, not his) to help groups who have a shared interest in a system understand their relationships.

Midgley worked in New Zealand for a number of years, where there was a question about why the country had high rates of food poisoning. One claim was that it was caused by the levels of animal waste in the water. In New Zealand anything that involves the dairy industry is a big deal: it represents more than half of the country’s exports.

His brief was not to solve the food poisoning issue, but to get the two sides talking. He got them to build their own causal maps, at which point they were willing to talk to each other. Rather than getting them to justify their maps, he asked them to walk the room and look for the things that connected their diagrams to others.

3. System

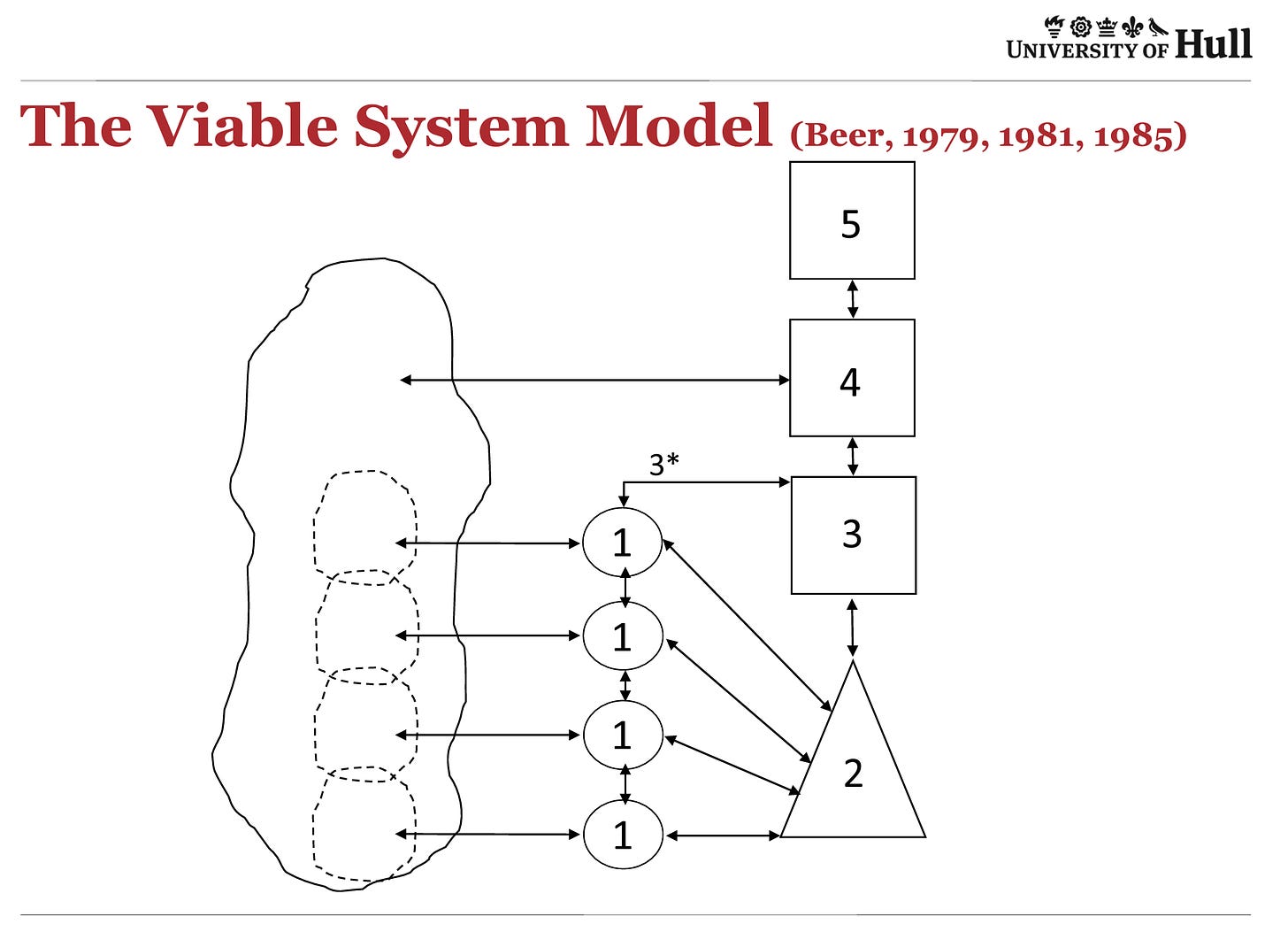

The system quadrant was pegged to Stafford Beer’s Viable System Model (VSM), which he developed in the late 1970s and early 1980s. (I wrote about the VSM in Just Two Things here; and about Stafford Beer more recently). This probably does need a diagram.

(Source: Gerald Midgeley)

There’s much more to this, but in brief, every organisation has an environment it interacts with. The VSM imagines the organisations as five types of system element. System 1 is the operational units—in his example, of a hospital during COVID, these are the wards, the operating theatres, and so on.

Operational units need some system of co-ordination, which is System 2–resourcing the staff, ensuring patients are routed to the right wards, and so on. System 3 is day-to-day management, monitoring operational performance — which is done by monitoring it and letting it run while performance runs between the normal levels of variance, and getting involved, in Beer’s phrase, only “by exception”.

System 4 is foresight—looking at threats and opportunities—while System 5 is about purpose and identity, the ethos of a system.

In the talk there’s a striking example of this approach being used by Pam Sydelko to redesign the system in Chicago under which different agencies engaged with international organised crime and local gang violence. Being good at local gang violence—killing people—was the best way to get recruited by one of the much more lucrative international gangs. The gang systems were related but the agencies weren’t.

4. Perspective

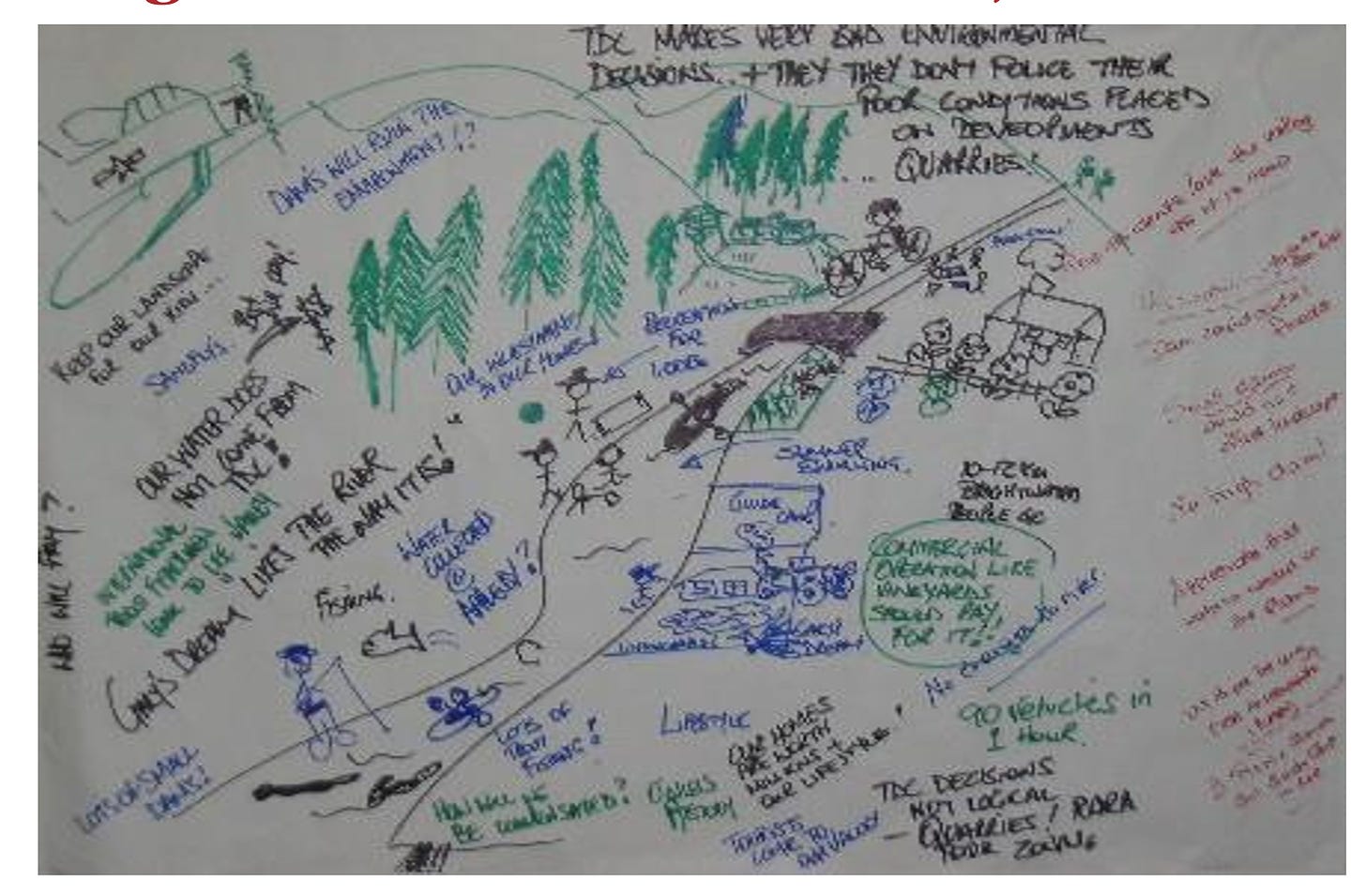

He used ‘perspective’ as a way to talk about Peter Checkland’s soft systems methodology. This proceeds by getting participants to draw a rich picture of the system, including the places where they disagree. There was an example of a rich picture in one of his slides.

(Source: Gerald Midgeley)

Checkland developed an acronym for the elements you needed to identify what was going on in a soft system, which Midgeley had adapted. He used ‘BATWOVE’, standing for Beneficiaries, Actors, Transformation, Worldview, Owners, Victims, Environment (or ‘external’) constraints.

(I don’t have space to go into this here, but there’s a good paper by Bob Williams online that explains both Checkland’s methodology and Midgeley evolution of it.)

The rich pictures map the activities and the agents involved in each transformation, and then look for what he called “accommodations”, and agree changes. He uses “accommodation” rather than “compromise” makes people defensive, and “accommodations” may be a new idea that comes out of the process.

Finally, in response to one of the questions, he talked about “the myth of ‘comprehensive understanding’. The point of systems work is to understand where there is a lack of comprehensiveness and comprehension.

The hour-long talk, and the questions that follow, can be seen on YouTube here. It is concise and well-structured:

A version of this article is also published on my Just Two Things Newsletter.