There’s a new report out from the International Monetary Fund that says that globally 40% of jobs will be affected by AI. That’s a big number, and frankly when you look across the trend in the literature on the impact of AI on work, it’s also a bit of an outlier. Sure, back in 2013 Frey and Osborne produced a model that that said that 47% of US jobs “were susceptible” to AI.

But generally, these numbers have been coming down in other studies over the last decade. So I thought it was worth trying to understand the IMF analysis a bit better. Because, on the face of it, it’s at least possible that there’s something else going on here.

Their full report is here, and here’s the summary on their blog, bylined by the IMF’s Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva.

Here’s the rather bald global summary:

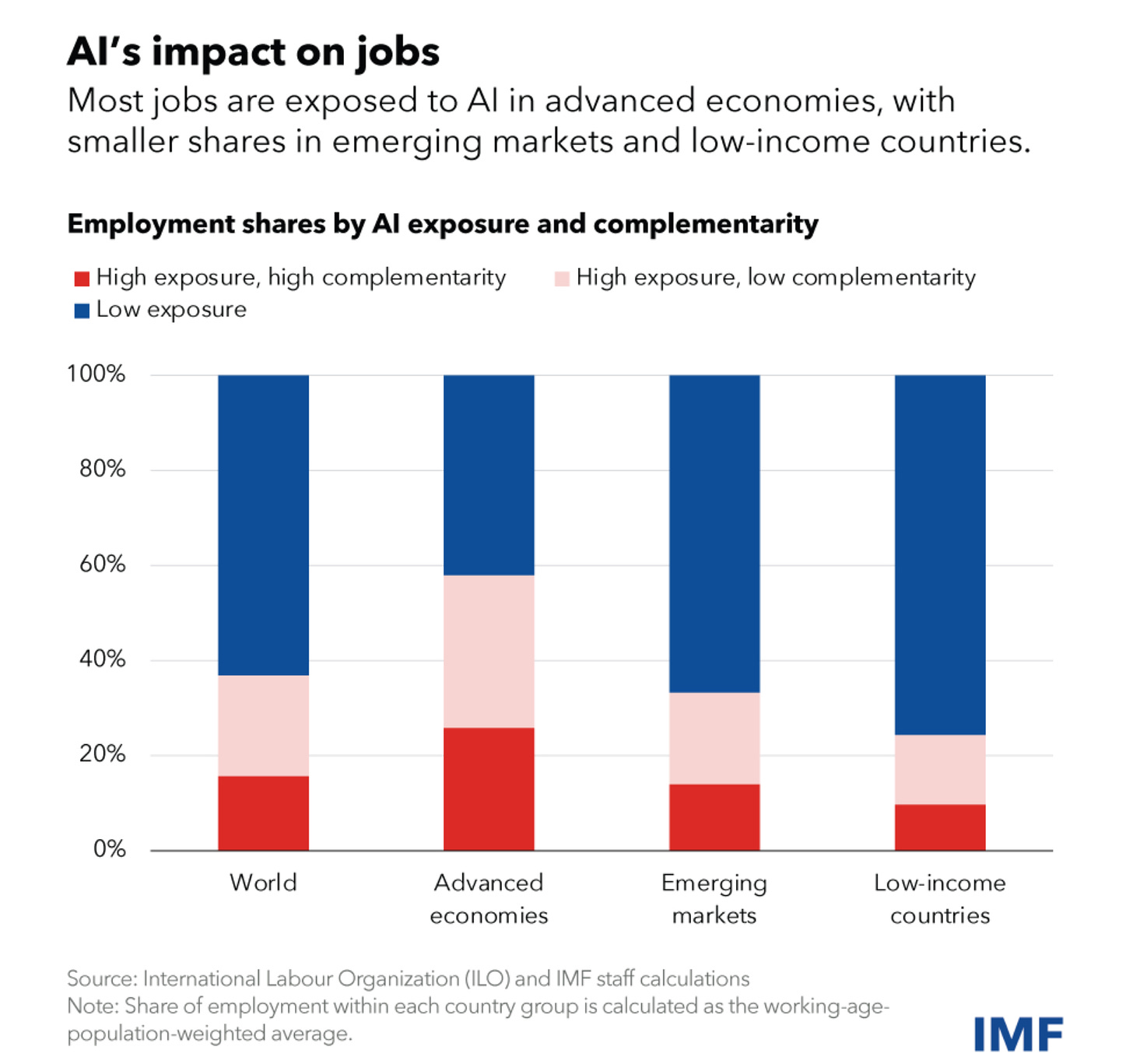

The findings are striking: almost 40 percent of global employment is exposed to AI. Historically, automation and information technology have tended to affect routine tasks, but one of the things that sets AI apart is its ability to impact high-skilled jobs. As a result, advanced economies face greater risks from AI—but also more opportunities to leverage its benefits—compared with emerging market and developing economies.

In advanced economies, they say, this figure rises to 60%; in emerging markets and low income countries, the figure is between 26% and 40%—less risk, but less exposure to benefits.

Discussion paper

The paper is positioned as a Staff Discussion Note, which is a way of saying that it doesn’t represent the formal view of the IMF. The authors say they are trying to add to the existing literature in four ways:

- instead of just looking at ‘exposure’ of particular jobs to AI, they are also trying to assess complementarity and substitution. This takes them into the context of particular jobs—social, ethical, physical;

- they try to assess the potential for workers to transition to roles with higher AI complementarity

- they seek to explore the impact of AI on wealth and income within countries;

- they look at the comparative preparedness of countries at different income levels to prepare for this shift.

So on the face of it, this seems like an attempt to get to a reasonably rich analysis, with some scope for benefits as well as shocks, although that’s not how it got covered in the media.

Modelling assumptions

And reading it as an interested lay person who tries to follow this literature, one of the modelling assumptions jumped out at me:

although in the model analysis activity grows in occupations with high AI complementarity and falls in low-complementarity occupations.

Because it’s not clear why that should be—the “low complementarity occupations” that they are talking about here are typically care or service jobs, and it’s not clear why activity should fall in these. Sure, you could use AI to help schedule a refuse truck route better, but it’s still going to involve people picking up rubbish from the street and dumping it into a truck. The acceptable ratio of nursery workers to children is unlikely to fall.

I’ll come back to this below.

Bundles of tasks

There are also some important caveats: workers will migrate to roles with different skills profiles, but the researchers don’t have a view on how long that will take (but I bet the model does). The pace of AI adoption is impossible to assess, or the rate at which firms will invest in it. But there does seem to be an large unstated assumption here that AI will have a big effect and it will work out exactly the way that firms that invest in it intend it to.

The idea of “complementarity” emerges from a model that says that jobs are bundles of tasks—and this is in line with the literature. It means that as technology or other circumstances change, the bundle of tasks tends to evolve in response. (They don’t use this example, but when I started work, there were still quite a lot of secretaries employed. Not so much now, but the parts of those jobs that involved organising things have turned into office coordinators, project managers, and executive assistants).

They add to this an idea of “shielding”: that society will place limits on some types of AI applications. They suggest, for example, that judges, who work with texts, are both exposed to AI but also shielded,

because society is currently unlikely to delegate judicial rulings to unsupervised AI.

‘Exposed’ or ‘shielded’

This, of course, is a large misunderstanding of what judges actually do, and suggests that economists ought to get out more, or at least read some social anthropology.

But to continue their analogy: clerical workers are exposed to AI and less shielded, although of course conventional computing has already had a pretty serious effect on clerical workers over the past 40 years.

Anyway, this framework gives them a three box model:

- “high exposure, high complementarity”;

- “high exposure, low complementarity”; and

- “low exposure”.

They see the first as being basically high-status cognitive knowledge work with high degrees of interaction: “surgeons, lawyers, and judges”. The second are less skilled: their example here is “telemarketers”. The third, they say, covers “a diverse range of professions, from dishwashers and performers to others.”

On/off

Apart from the slightly strange examples, it’s unclear what sort of tasks they consider to be exposed to AI, or what mix in the task bundle makes the different between “high” or “low” exposure. You can’t help but think that this really needs to be, say, a five point scale across these two dimensions rather than an on/off switch.

And there’s no sense that occupations might gain from AI. Anecdotally, for example, I was told by a head who was using AI to help his teachers do their admin that it had reduced fatigue and stress levels because it helped them to focus on the parts of the jobs that were about education.

The problem with not having enough granularity here means that it is hard to assess a lot of the other claims that are being made here. But let me note them anyway:

- The share of employment at risk of displacement — high-exposure, low-complementarity— is broadly similar across income quantiles

- This is different from previous waves of automation and information technology, where risks of displacement were highest for middle-income earners

- But employment in high-exposure, high-complementarity jobs, where they expect the income gains to be made, is more concentrated in the upper-income quantiles.

Technology impacts

I’ve focussed here on the assumptions in the report about specific job types rather than the country discussion. And this post is already too long. But there is a couple of things to add.

Once you have this model, the implication is that inequality increases—and hence the IMF press release headline. The study uses the recent history of the UK as a way of calibrating the relative impact of technology change on the labour share of income, on the basis that the UK is relatively exposed to AI use. The time period they choose is 1980-2014. From this,

we assume that the labor share declines by 5.5 percentage points following the introduction of AI.

But there are a few other quite important factors that led to much of this decline in the UK: deregulation and privatisation, a sustained political assault on the power of the trades unions, the opening up of global production in Asia.[1] This may be getting things the wrong way around. (David Autor came to a similar conclusion about the decline in labour share of income in the US over a similar period: technology was a factor, but not the lead factor).

Given that the IMF was instrumental in advocating for much of this, across the world, perhaps the researchers are blind to it: there’s not enough detail in the report to work out if they have taken this into account or not.

So what’s the IMF’s interest here? Probably trying to maintain relevance in a world where its previous world view is largely discredited. Because otherwise the Managing Director wouldn’t have signed the blog post.

——

[1] In the text they say: ”The decrease in the labor share has historically been associated with routine-biased automation and, to a lesser extent, with increased trade, growing markups, and declining worker bargaining power resulting from the weakening of labor unions.”

A version of this article is also published on my Just Two Things Newsletter.