I’ll write more here soon about the some of the structural questions raised by the UK General Election, notably the continuing decomposition of the 2024 Conservative party. But one of the lessons of the general election campaign has been is the inability of politicians to talk about difficult issues, especially about economics.

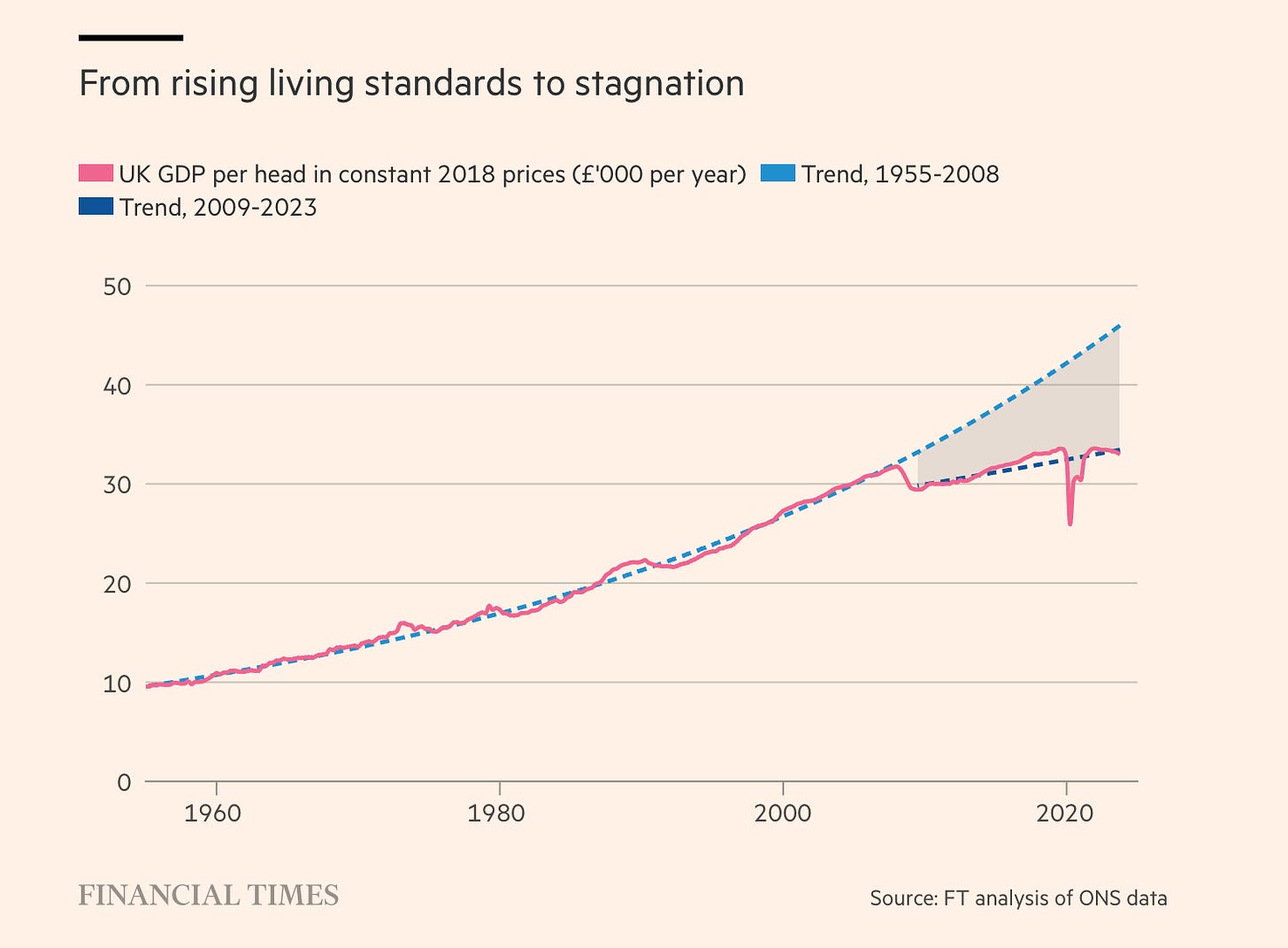

Because this chart (taken in this version from a column by Martin Wolf in the Financial Times) is really the only thing you need to know about British politics at the moment.

(Source: FT analysis of UK data)

What it shows is that after 2008, or so, the British economy fell off the track of the rate of growth that it had been on for the previous 50 years, and jumped to another track.

That trend line from 1960-2010 had not been particularly compelling—it was still slower than other comparable economies—but it did trend upwards.

Austerity policies

The best single explanation of this is the austerity policies that the Cameron-Osborne led Coalition government chose to follow, ostensibly to deal with the level of government debt incurred in dealing with the financial crisis.

There are different versions of why they opted for this.[1] The plain vanilla version of this is that Osborne saw a presentation by Reinhart and Rogoff of their 2010 research paper that said that when debt climbed above 90% of annual GDP it choked off growth. This is, of course, the research paper that has the most famous spreadsheet error in economics history.

It’s worth spelling out the mistake:

[T]his 90% figure was employed repeatedly in political arguments over high-profile austerity measures… The most serious [of three errors identified] was that, in their Excel spreadsheet, Reinhart and Rogoff had not selected the entire row when averaging growth figures: they omitted data from Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada and Denmark… When that error was corrected, the “0.1% decline” data became a 2.2% average increase in economic growth.

This error was exposed in 2013, and Osborne did not change his policy as a result, even though austerity had evidently not improved growth by then.

Cutting state spending

So a more credible explanation is that he believed in cutting back state spending for ideological reasons. He also finagled his cuts in such a way that local councils would be blamed from them rather than central government, which is why many British councils are currently at risk of bankruptcy. [2]

The most direct political consequence of these continuing cuts to the UK social fabric, and slower economic growth was the vote in favour of Brexit. There is research by Thiemo Fetzer at Warwick Universitythat suggests that austerity and its related welfare measures was enough to swing the vote from Remain to Leave.[3]

Either way, the effect of these two, in combination, was enough to create a cycle in which business confidence declined and therefore business investment declined, leading to lower growth—and stagnating wages. I could do a causal loop diagram of this, but in 2024, what this lost decade and a half means in practice—according to the economist Simon Wren-Lewis is that households have lost £35,000 in resources, measured in today’s prices, over the last 15 years.

Smaller tax base

And as a result the UK tax base is correspondingly smaller. (It’s possible to argue about whether growth is a sensible target, but higher productivity, which always requires investment in people and systems, is almost always worth having more of). Higher productivity creates social and economic opportunity, including opportunity for shorter working hours).

Here’s an IMF chart, also via the Financial Times, from the same Martin Wolf column referenced above, that tells the same story in a comparative way.

(Source: Financial Times chart from International Monetary Fund)

That’s Britain, down near the bottom.

So, in effect, the only way that British citizens can have nicer things, at least in terms of public services, is if the Government can find ways to end this 15-year stagnation.

‘Strategic state’

The odd thing about this is that outside of the revanchists on the right of the Conservative Party, there’s not much disagreement about this. Rachel Reeves, who seems likely to be the UK Chancellor of the Exchequer this time next week, addressed it in a Mais Lecture early this year.

Her mantra then was about the “smart and strategic state”, whatever that means. Underlying this, though, she was clear that more stagnation could put democracy at risk, and that policy needed to reduce regional inequality. Her recipe for doing something about it then was, in Martin Wolf’s summary,

stability; “stimulating investment through partnership with business”; and reforms that will unlock productivity.

This sounds as if it is heading in the right direction, even if it probably isn’t enough to deal with the scale of the problem. In practice, when she gave that lecture in March, she talked about new public institutions to help enable investment, using pension fund investment more strategically, and dealing with the UK’s planning system.[4]

Dealing with insecurity

Since then, as we have got into an election, we have also seen proposals to deal with in-work poverty and insecurity. These would probably increase productivity, even though they appear to have been misunderstood and then criticised by Britain’s keepers of economic orthodoxy, as Paul Mason pointed out in a thread on Twitter/X last week.

When I say that there’s not much disagreement on this, it’s because the Conservatives Nick Timothy and Gavin Rice have recently written a paper—endorsed by the Conservative front-bench politician Michael Gove—that says much the same thing, even if some of the policy emphasis varies.[5] (My thanks to Ian Christie for sending it over to me.) The paper, published by the Onward group, argues that

[W]e face huge challenges from low household incomes and regional imbalances to poor productivity and a lack of investment… The paper makes the case for an active industrial strategy to rebuild Britain’s manufacturing base, boost exports and make it less reliant on overseas ownership of its core strategic assets. It calls for an economic policy to prioritise national productivity and security over international rent-seeking or libertarian ideology.

What’s left out

What’s striking about these analyses, though, is what they leave out. The ‘Overton Window’ on financing government expenditure has become miserably small.

Indeed, one of the most depressing political moments of the year was in Starmer’s budget response speech, when he accused the government of “maxing out” the nation’s credit card. This was exactly the attack line Osborne and Cameron used against Labour after the financial crisis to justify austerity, so Starmer probably thought he was being clever. But it can’t be said often enough: nations aren’t households. And nations that have control over their own currencies even less so.

The tax story being told during the election has only the most trivial ideas—and only hinted at—on taxing wealth. This involves bringing Capital Gains Tax up to the same rate as income tax, which should have been done on tax equity grounds a long time ago. It is mute on the economic benefits of forms of public ownership. And discussion of the way public investment actually works in practice has been primitive.

So primitive, in fact, that bond market traders popped up in the Financial Times to tell Rachel Reeves that the bond markets would be completely happy if she raised bonds to invest in infrastructure. (The way she and Labour leader Keir Starmer walked back from their earlier proposals to invest £28 billion on transition/climate infrastructure was one of the most embarrassing acts of their leadership).

Borrowing to invest

That’s behind a paywall, so here’s an extract:

“If Labour borrows to invest, markets will not worry about it,” said Tom Roderick, portfolio manager at hedge fund firm Trium Capital. “What markets are more worried about is borrowing to cut taxes, or increase social security payments, which doesn’t sound that likely.”

It’s quite an achievement for the Labour party to be to the right of the bond markets. But the important point here is that the only likely way to end stagnation is by government taking the lead on investment, as the Biden administration did. And not doing it in a way that could potentially be transformational because you have got confused about some basic economic principles would be unforgivable. People keep telling me that neoliberalism is dead, but its cold bony hand is still gripped tight around the imaginations of our political class.

—

[1] John Naughton, who mentioned this piece in his Memex 1.1 blog, added a further version:

“One (not mentioned by Andrew) is the ludicrous narrative foisted on a credulous British public by George Osborne (the Chancellor and the brains behind the Cameron government) that the huge sovereign debt run up the the Brown administration to bail out the banks was in fact just a typical example of Labour profligacy — so that, just as households who run up too much debt must eventually tighten their belts, so too must the UK.”

[2] ‘Friends of George’—to use a tired journalistic cliche about off the record briefing—also spent much of the early Coalition years telling journalists that George was a political strategy genius because of this attempted misdirection, which claims journalists seemed happy to publish without thinking about them at all.

[3] If you are interested in this it’s also worth reading the discussion rebutting critics of the paper.

[4] Wolf assumed that the British Treasury (finance ministry)—which has been party to the wrecking of the British economy because of its narrow and rigid thinking—would do the best it could to kill off the proposals for new public institutions, whether or not they were a good idea. The question of the British planning system is worth coming back to another time—because in a financialised economy it’s not quite as simple as this.

[5] Yes, this is the same Michael Gove who has been in the government for most of past 15 years; yes, this is the same Nick Timothy—now an MP—who worked closely with Theresa May when she was Britain’s Prime Minister.

—-

A version of this article was also published on my Just Two Things Newsletter.