I’ve been aware of the concept of “literary futures” since I attended a workshop at Lancaster University’s then Institute for Social Futures in early 2020.[1] Emily Spiers ran a narrative futures component in an all-day workshop that was, presciently, about biohazards. That work has been taken further by Emily’s former colleague Rebecca Braun, now at the University of Galway, and she has just published a paper called ‘Literary Futures: Harnessing fiction for futures work’ with two Galway colleagues.

It’s an interesting approach, and I am going to point to some highlights here. The whole paper is in front of the Futures paywall. But a bunch of disclosures here: I have worked with Rebecca and have met her two colleagues; I reviewed an early draft of this paper; and I made a modest methodological suggestion, generously credited in the paper, as the approach was starting to evolve.

The paper documents the approach and has some quantitative analysis of some of the workshops involved in developing the method. I’m going to focus on the first part of this here.

A core tool

But let’s start with the core claim of literary futures:

Central to the Literary Futures method is the notion that literature itself – as both an object of study and a process of creative engagement – should be considered a core tool for imagining and acting upon social futures.

In doing this, it is positioning itself in the group of futures methods that has emerged into the mainstream since the 1990s, which are informed by culture, values, politics, and, come to that, agency, as against the more technocratic and positivist futures of the business and military world.

But: it’s not about using science fiction or other futures-oriented texts. Instead:

(I)t is grounded in those formal and structural features of literary texts that underpin the fundamental activity involved in imagining alternative worlds from various perspectives, and in applying these in a practical way to engage in futures thinking: telling a story in a linguistically and conceptually engaging way that uses the power of metaphor, imagery, character and plot to allow both projection into an alternative time and place and reflection back on the reader’s contemporary reality.

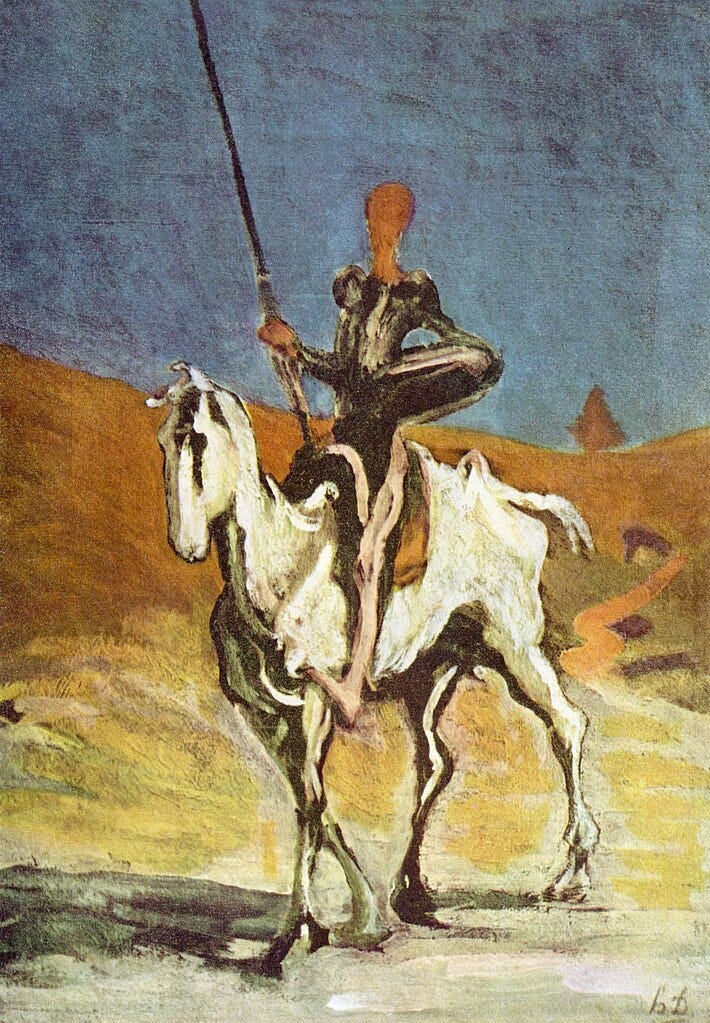

(Don Quijote, by Honoré Daumier, circa 1868)

The canon

And so the Literary Futures method has, in effect, headed in exactly the opposite direction from science fiction, to texts that are part of the Western canon. (I imagine that people using it in other cultures could draw on their canon instead). In fact, the example given in the article is Cervantes’ Don Quixote.

(Quixote’s) world is not bound by traditional linear chronology, offering the reader instead space to imagine alternative (social) worlds, holding a variety of perspectives in view simultaneously. On multiple levels, then, Don Quixote in fact acts as a meta-narrative for foregrounding both the challenges and the opportunities of doing futures work.

The paper describes a workshop approach to using literary futures, and there’s probably just enough here to encourage people to try this at home, or at least in a pilot workshop of their own. It unfolds in three stages:

- Character development

- Worldbuilding

- Integrating futures techniques

Character development

The literary futures method starts with character, not with worldbuilding. The rationale for this is both theoretical and practical. Theoretical:

characters play an important role in enabling the reader to engage with diverse and multiple perspectives and with the felt experiences of others and their interpretations of the world. This offer of “inner dimensions” makes literary fiction a rich resource for experiential approaches to futuring.

In practice, it works like this:

This is designed to be an empowering experience that involves making a series of quick decisions… The characters are developed through an open process, with a set of standard character development questions acting as a template to get started as opposed to a rigid set of instructions. These characters are not being designed to a specific end or in relation to a pre-determined future scenario. Rather, the emphasis is on creating a well-rounded character, shaped by a backstory and values, and an understanding of how they behave with and interact with others.

From a process point of view, it is worth noting that the characters are built individually by the participants, not in discussion with the other members of their group.

Worldbuilding

The worldbuilding stage then uses the characters and their interaction to build the world(s).

Participants are asked to consider where their characters are, what they are doing, who they are with and what interactions are taking place. This activity is supported by a prompt that involves putting a group of characters together (c. five characters/participants) at a given point in the future and providing one significant piece of information about this future world.

The prompt is broad: the example given in the article is:

“It is 2040 (or date 20 years into the future), and the world is wholly reliant on renewable energy”.

It is then down to the characters to find their way in this world together.

Both as a participant in Emily Spiers workshop and running a workshop based on the method—building images of Piccadilly in 2100—I found this approach profoundly liberating. You can get some genuinely open futures as the characters start to mesh into their worlds. In the Piccadilly workshop, we had a baby with super-cognitive powers that had escaped from its parents, for example. Perhaps this is because:

At this point in the workshop, an ‘anything goes’ approach is adopted and participants are encouraged to think creatively around any apparent stumbling blocks in their story (for example having created a medieval character or having a set of characters scattered around the globe).

Integrating futures techniques

The final step is trying to bring the worlds to life in practical terms. The method uses Lum and Bowman’s Verge framework, which is an ethnographic approach to building out how a world works in practice. You can read that at the link, so I won’t expand on it here, except to quote the article briefly:

Of particular value here is the focus on (human) experience under six domains: Define, Relate, Connect, Create, Consume, and Destroy… Incorporating this futures technique moves the Literary Futures method from an exercise in pure imagination to one that offers insights into the concrete and practical nature of the worlds that are developed. This makes these worlds more tangible, bringing them to life through the eyes of multiple characters.

The second futures tool that gets deployed is backcasting, to work back from their emerging future world to the present and visualise some of the things that might have happened on the road to this particular future. Again, this opens up discussions about the topic under consideration from a range of different perspectives.

My experience of the method suggests that it produces vignettes—stories with a clear centre of gravity that allows the world to come into focus—rather than full scenarios. Equally, though, that also means that people think more freely about the future, and starting from the characters before dropping them into the future is particularly liberating here.

In that Lancaster workshop, her colleague Derek Gatherer opened it with a quick game of Consequences, with a starting prompt for each table based on the workshop theme, with each sheet going round the room.[2] This created energy in the room, built up a repertoire of ideas, and freed up thinking. When I ran my Piccadilly workshop, I repeated the trick and it had the same effect.

—

[1] Declaration of interest: I was a member of the advisory board for the Institute of Social Futures from its creation in 2016 until Lancaster University transmuted it (meaning: de-funded it) into a Centre for Futures Studies last year. But while it was funded it was a good example of how futures can act as a centre of inter-disciplinary thinking and of inter-disciplinary innovation.

[2] Updated on 25 March 2024. The original post credited the Consequences game to Emily Spiers.