I have always had a lot of time for the doctor and scientist David Nutt. I was lucky enough to work with him about 20 years ago on a UK Foresight scenarios project on ‘Brain science, addiction and drugs’, and he has been a consistent voice trying to align British drugs policy with actual evidence of harm, although that particular project is like trying to push water up a hill.

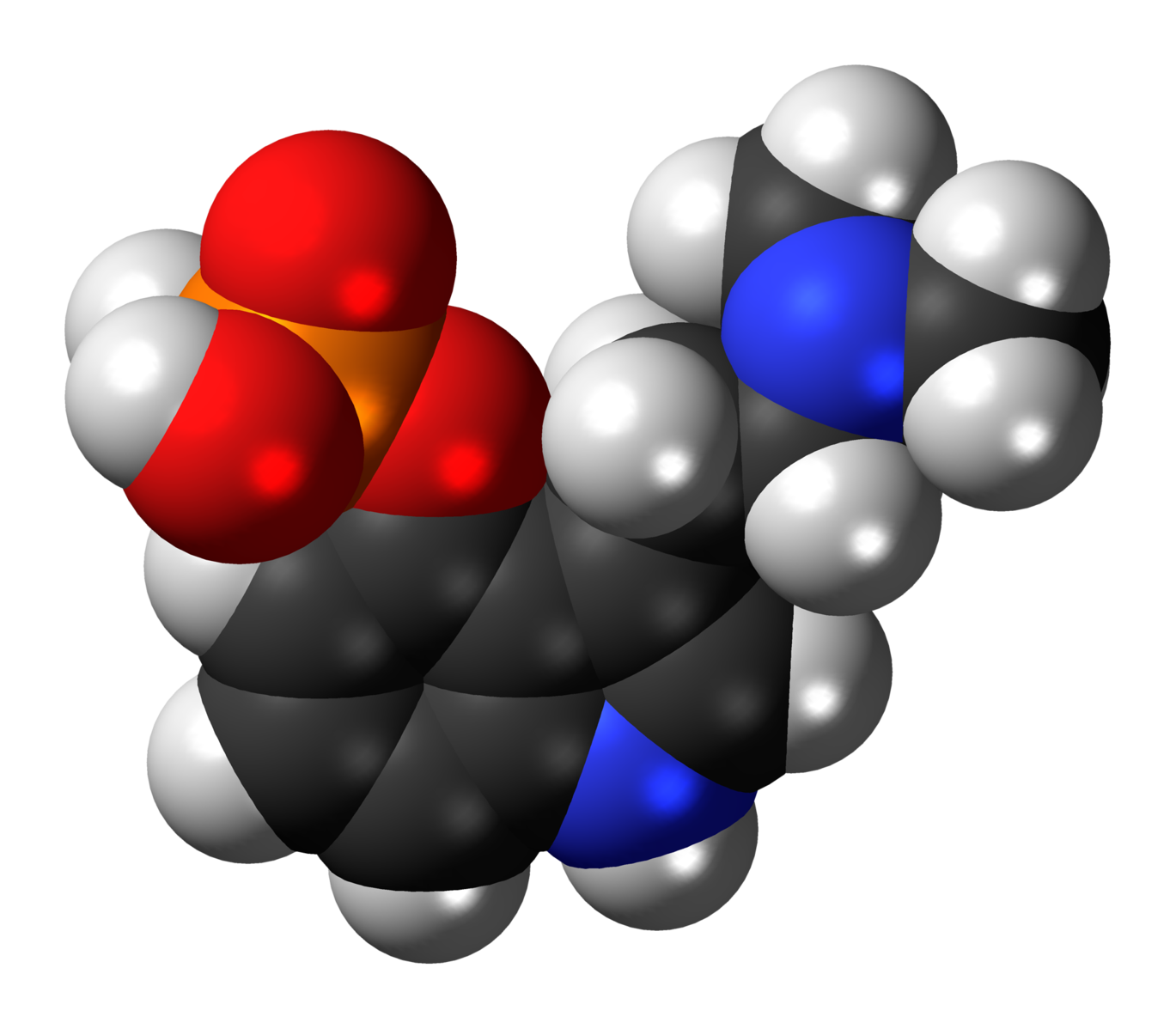

He was at Unherd a while ago talking to Florence Read about psilocybin and depression, which is a subject I have touched on in different ways here before. For me, this is one of those signals of change which could suddenly move quite quickly. Yes, society has views on psilocybins, which were outlawed here 50 years ago, but it also has an increasingly big problem with depression.

Both the research, and the responses to it, are interesting. It’s also a long interview transcript, so I’ll have to be selective.

‘They all got better’

The headline on the piece was: “Can psychedelics cure depression?” But let’s do the science first.

Psychedelics switch off the parts of the brain that control your mind. There was a group at Yale doing work in depression. They showed that the default mode network — the part of the brain that was turned off by psychedelics — is overactive in depression. If you scan the brains of depressed people, a greater amount of their brain is engaged in this internal, reflective, self-referential thinking. We thought: “Let’s see if we can turn it off in depressed people, and will they be non-depressed?” And lo and behold, they were.

As Nutt observes, the 1960s radical Timothy Leary got it the wrong way round: psychedelics weren’t turning the brain on, they were turning it off.

The initial study group for Nutt’s research was people who were depressed, and who had failed with other treatments, whether anti-depressants or CBT (cognitive behavioural therapy). And: “They all got better”.

Lowering the barriers

But, reading the interview, it’s not just the psilocybin that’s doing this. The use of psychedelics is combined with therapy: what the psychedelics are doing is (as I understand it) lowering the barriers to engaging with the trauma that is causing the depression. The reason that this might work:

(O)ne of the theories about why your mind is so preoccupied in depression — is that you’re trying to resist re-engaging with those traumas. But we encouraged them to do that. It’s challenging, it’s difficult, they find it distressing — but they often get fundamental insights.

There seems to be something about psilocybin that makes the medical establishment a little jittery, though. Having got a grant in response to a Medical Research Council call for research on new treatments for depression, it took a years and three re-designs to get the research design past the Ethics Committee. For example:

The ethics committee said: “It’s too dangerous; you can’t give depressed people psychedelics.” Why not? “Well, they might die.” That’s pretty unlikely — no one’s ever died on psilocybin before — but why do you think depressed people might die? “Well, they’re depressed.”

Safety study

The Ethics Committee turned down the proposed random controlled trial—for the same safety reasons—and instead proposed that the researchers start with a safety study:

Give 12 people it, see how they go. If none of them are dead in six months then you can come back and do a controlled trial.” So we said yes — in fact, the original trial was to see if people survived, which they all did. And the secondary outcome was whether their mood had changed. They could have got worse. They all got better.

That was only one of the delays to the project. It took another year to get hold of the drug because there’s only one place in the world able to make it. And then it took another two months to get permission from the Home Office to use it.

Thinking differently

Nutt suggests that these delays are because of the way that psychedelics have been “vilified” (his word) over the last half a century. Of course, there’s a history here too:

The reason psychedelics were banned in 1967 in the US and in 1970 in the UK was simply because psychedelics were allowing people to think differently about how they wanted to run international relations. The war in Vietnam was being protested. There’s this amazing photograph I have, of someone holding a placard that says: “Drop acid, not bombs.” They couldn’t ban the anti-war protests so they banned the drugs instead.

Nutt observes that drugs laws are very hard to shift. They’re certainly not that responsive to evidence. But all the same, things are changing. In the US half of the states now permit the recreational use of cannabis, and two thirds medicinal use, even though its still illegal at a federal law. Canada and Uruguay have pulled canabis out of the UN conventions.

None of that has happened yet to psilocybins, but Oregon has now made magic mushrooms a legal medicine, and are allowing wellness centres across the state to prescribe mushrooms as part of a wellness therapy.

It’s the first time anywhere in America that there’s kind of socialised medicine — using what it is now, and will be even when the therapy centres are open, an illegal drug. The purpose is to improve wellbeing in communities, and I think it’s going to work.

Cultural responses

Nutt isn’t confident that British doctors will follow suit, or not yet. He describes healthcare in the UK as “top-down, paternalistic and autocratic.” But at the same time there is strong academic interest, and the research is being published in leading science journals. The medical response seems more cultural. In the interview, Nutt describes giving a talk on this about five years ago yo the Royal College of Psychiatry, as part of a discussion on the future of psychiatry. By his account, the room split into three groups.

The older group—who could remember psychedelics when they were still legal, were pleased that Nutt was bringing them back into medicine. The middle group (then 35 to 60, so Boomers and GenX doctors) were sceptical or hostile:

“This is rubbish. There’s no RCTs. They’re dangerous drugs.”

And the trainees—effectively the Millennials in the room:

“Fantastic — at last. Psychiatry has got something to offer me!”

And this age-related cultural point is another reason why I think this area could move quickly when it starts to move.

—

A version of this article is also published on my Just Two Things Newsletter.