It’s been an interesting few weeks for politics, or at least for elections. But I gave up journalism several decades ago because I was more interested in structure than headlines, so I’ve been trying to think about this structurally.

This means that I’m more interested in Zohran Mamdani’s Mayoralty election win in New York, and the by-election win in Wales by Plaid Cymru (over Reform UK) in what was a safe Labour seat, for what they tell us about politics more broadly.

The first port-of-call, then, is a report issued by the US NGO Democracy 2076 last week. Democracy 2076

provides strategies to inspire renewed faith in pro-democratic, pro-topian futures that moves people to action in service of a resilient democracy.

And usual disclosures: I have met the Director and Deputy Director, and some of my colleagues at School of International Futures contributed to the report I’m going to discuss here.

Of course, promoting faith in democracy and action in its service is a tough row to hoe in the US right now. But part of their starting point, in the report and more generally, is the observation by Walter Burnham that in the US, the main political parties have gone through significant alignment every 30-40 years or so. Democracy 2076 sees us as going through that moment right now: in other words, there is everything to play for.

Long term change

Theories of long-term change are like catnap to futurists in general, or at least to me in particular. Realignment theory is a bit controversial; there are multiple theories, not just Burnham’s; and there’s been a lot of critique of it. All the same, there’s a similar (and perhaps connected) theory by the US political scientist Gary Gerstle, of “political orders”, which comes into this space from political economy rather than political science or election analysis.

Gerstle similarly sees 40-year periods in which there is a dominant view of how the world works, which then shapes law, regulation, institutional behaviour, and so on. He’s written and edited books about both the New Deal and neoliberalism.

As he puts it in an interview:

Political orders are complex networks of institutions, constituencies, big-pocketed donors, and interest groups. If they are successful in establishing themselves, they can have enormous staying power and can enforce a kind of ideological hegemony on politics, not just on members of their own party but on members of the opposition.

Being an historian Gerstle is careful to suggest that this isn’t an iron law of history—as far as he’s concerned we just happen to have seen two forty year-ish periods.1

Governing crisis

But it useful to consider why these periods of “ideological hegemony” come to an end:

A political order usually breaks up as a result of an economic crisis big and severe enough to cause a governing crisis, during which existing formulas for managing the economy and the polity no longer work. Chaos and failure to enact successful policies, and the popular protest that results from such failures, create an opportunity for political ideas long consigned to the margins to move to the mainstream.

So it’s probably worth my while saying that I suspect that the political science theories about realignment are symptoms of these deeper changes.

So this is a good point to go back to Democracy 2076 and some of the detail in their report. In my view it’s unnecessarily complicated, although I can see what they’re trying to do. They’ve identified 17 tensions, under six headings.2 There’s no simple way to unpack them all, but the headings are: identity; geography and economics; governance and authority; values; demographics and generations; and political structures and international dynamics.

They also have five scenarios, although the relationship between the tensions and the scenarios is a bit uneven.

And some of the tensions are problematic, in that it is possible to believe one end of them from completely different political positions. For example, the very first one: “education as a social equalizer” vs “education as a status reinforcer”. You can believe the second of these be true, and that this is a good thing—or that it is true, but a bad thing, from either a Marxist or populist position of critique.

Political realignment

In a post that’s partly behind a paywall, the British blogger Joxley goes to the other extreme and suggests that politics is in the process of realigning from a left-right (primarily economic) axis to an open-closed (primarily attitudinal) axis:

The definitions are contested and fluid, but broadly mean those who are internationalist and committed to the global liberal order on one side, versus those who are insular, national, and nativist on the other.

If Democracy 2076 is a bit too complicated, I think that this is a bit too simple. When you think about the Political Compass, say, it adds a second social dimension (authoritarian-liberal) to the economic dimension that runs from left to right.

Joxley is specifically interested in the future of the centre-right party, and specifically in Britain, which has historically been the most successful ruling party in Europe. But it is also a creature of economic alignment, and he wonders where it can go in an open-closed world.

But I think what might be happening here is a bit more straightforward. The open-closed axis looks quite like the authoritarian-liberalism axis in the Political Compass, with open at the bottom and closed at the top. The economic axis is still there, but has been rewritten by the Global Financial Crisis and its aftermath.

The ‘credentialled precariat’

The demographic-structuralist theorist Peter Turchin doesn’t normally write about current affairs (a recent post focused on the impact of the invention of horse spurs on empire size in the middle ages). But he made an exception after Mamdani’s election. In a post he referenced his book End Times (I reviewed this here), where he wrote about the growth of the ‘credentialed precariat’, who have degrees but are also saddled with debt and high living costs. (The most recent group of degree holders is also being squeezed out of entry-level work by companies using AI as a short-run cost-cutting device.)

In End Times, Turchin characterised American politics—this is the broad brushstrokes version—as benefitting only a small fraction of the electorate:

Ten years ago the political landscape in the US was dominated by two parties: one of the “1 percent” (wealth holders) and one of the “10 percent” (credential-holders). Both parties focused on advancing the interests of the ruling class, while ignoring those of the 90 percent.

We know how that ended up. Trump channelled that into the capture of the Republican Party by MAGA. In places like New York, degree holders are less likely to opt for right-wing populist politics. But looking at one of Democracy 2076’s ‘tensions’, both might agree that current institutions—particularly economic institutions—need dismantling rather than mere improvement.

Turchin reviews Mamdani’s exit poll numbers and says that they

provide strong support for the idea that Mamdani’s win was largely propelled by the young credentialed precariat: the youth with college degree, or higher, earning just enough to live on the edge.

Blocked from mobility

And he points to a piece by John Carney in Commonplacemagazine, written when Mamdani won the Democrat nomination against expectations:

The neighborhoods where Mamdani won [the nomination are] zones of post-industrial drift, populated by nonprofit managers, freelance writers, overburdened teachers, and software engineers who live paycheck to paycheck despite six-figure incomes. This is a class increasingly defined by contradiction: culturally elite, economically unstable, and structurally blocked from mobility.

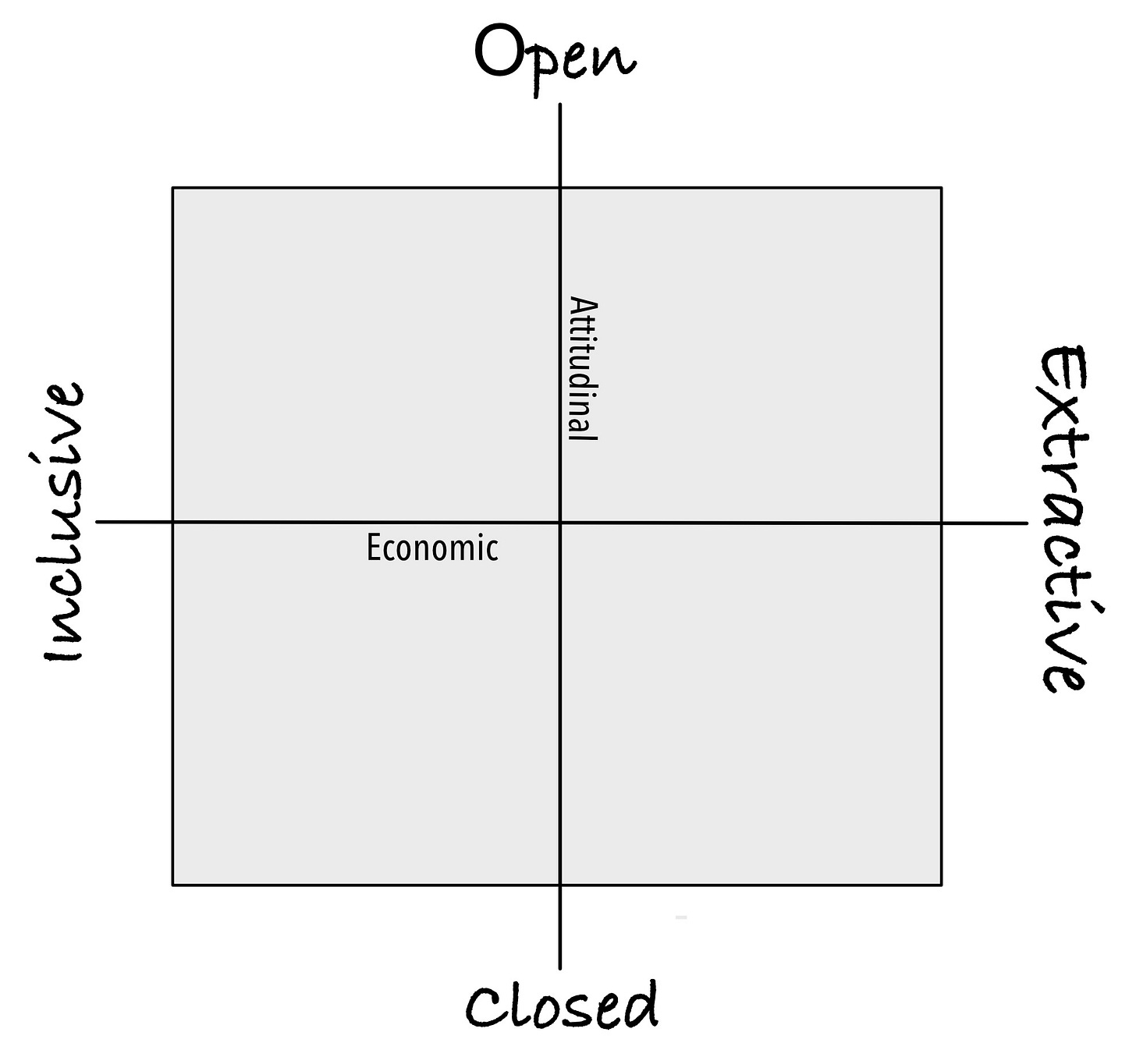

So all of this suggests to me that there is still an economic axis here, but it runs from something like ‘inclusive economics’ to ‘extractive economics’, depending on who the economy is being run for. We can take ‘extractive’ as a shorthand for a whole range of rentier business models, including debt-driven private equity ownership and enshittification by Big and Small Tech, which have been encouraged by the lax regulation and weak competition law under the neoliberal ‘regime’.

What’s striking about this simple, even simplistic, diagram, is that it still tells you a lot about the potential for political realignment. In the US, generally, the Democrats are still trapped in the world of Wall Street and Big Tech, in the top right. In the UK, the Labour party lurches around the map, sometimes Open, sometimes Closed (cf Palestine Action), but definitely in hock intellectually to the rentiers of the Extractive economy, whom they wrongly associate with economic growth.

Trump, meanwhile, talks Closed/Inclusive while doing Closed/Extractive, which is one the reasons his polling numbers have plummeted.

Political energy

And all the energy is on the other side, both in the US and the UK. Mamdani is Open/Inclusive, while MAGA is Closed and against Extractive: although it lacks a coherent economic philosophy, it is largely dependent economically on those bits of the US government system that try to be inclusive (and which Trump and Russell Vought are trying to dismantle). In the UK, the Green Party (and in Wales, Plaid Cymru) are clearly Open/Inclusive, which is why they are peeling polling support away from Labour. You might notice a pattern here.

And not just in the Anglosphere. Since I wrote the original version of this post on Just Two Things, Crispin Mudde, who studies the far right, noted in The Guardian that Copenhagen no longer has a Social Democrat Mayor. The Green Left (SF) candidate won. For British readers watching the Labour Party aping the Danish immigration model, there might be a certain irony here.

In contrast, the hard-right Reform UK mirrors Trump; certainly Closed but disguising a love of Extraction with populist economic rhetoric about Inclusiveness.

This contradiction suggests that populist right wing parties will tend to come unstuck if they get too close to government. In the UK we’re seeing some of this in the councils that Reform UK won earlier this year. At heart, they are creatures of crisis that thrive as a ‘political order’ is breaking up.

Some of this might also suggest that Joxley is wrong about the prospects for the centre-right, although it will need more imagination than they have shown signs of in the last decade. But you could see a form of Conservatism that represented a light version of the Closed axis combined with some traditional support for more local businesses, rather than hedge funds.

Wrong-headed

But it also suggests that in the UK (and elsewhere) a social democratic political strategy that is about appeasing potential Reform voters is wrong-headed, and we have UK data on this. (TL: DR: it is wrong-headed). Simon Wren-Lewis’ Mainly Macro blog shares data about this in the UK from the political scientist Ben Ansell. He uses a pair of economic/cultural attitudes axes, but confusingly swapped from the two above, so economics goes up and cultural attitudes go across.

Part of the Labour theory is driven by an idea, possibly originating from its political strategist Morgan McSweeney, that its potential voters in marginals and super-marginals are wildly different from voters in safer Labour seats. Although there is a view inside the Labour Party that Morgan McSweeney is some kind of political genius, this theory is a long way off the mark.

What this shows is that the (colour-coded) voters for each party cluster around the same set of economic and social views, regardless of how marginal or safe the seat is. The grey blobs in the middle are the don’t knows. As Ansell says:

What I think Blue Labour believe is that Labour voters in the marginal Red Wall district have fundamentally different views on social (and maybe economic) issues than Labour voters in safe London seats. They don’t… the differences among voters are among voters not constituencies. Ecological inference is a hell of a drug. [3]

Ageing voters

In his Guardian piece, Cas Mudde says that chasing hard-right votes is a mistake in both the short-term and the long-term:

This strategy is not just unsuccessful in the short run; by failing to win over these voters, it leads to the loss of progressive voters and prevents the rejuvenation of their ageing electorate in the future… Whereas social-democratic parties have some of the oldest electorates… their left competitors are particularly popular among young voters, including many with a minority background.

Some of all of this might also suggest that Joxley is wrong about the prospects for the centre-right, although it will need more imagination than they have shown signs of in the last decade. But you could see a form of Conservatism that represented a light version of the Closed axis combined with some traditional support for more local businesses, rather than hedge funds.

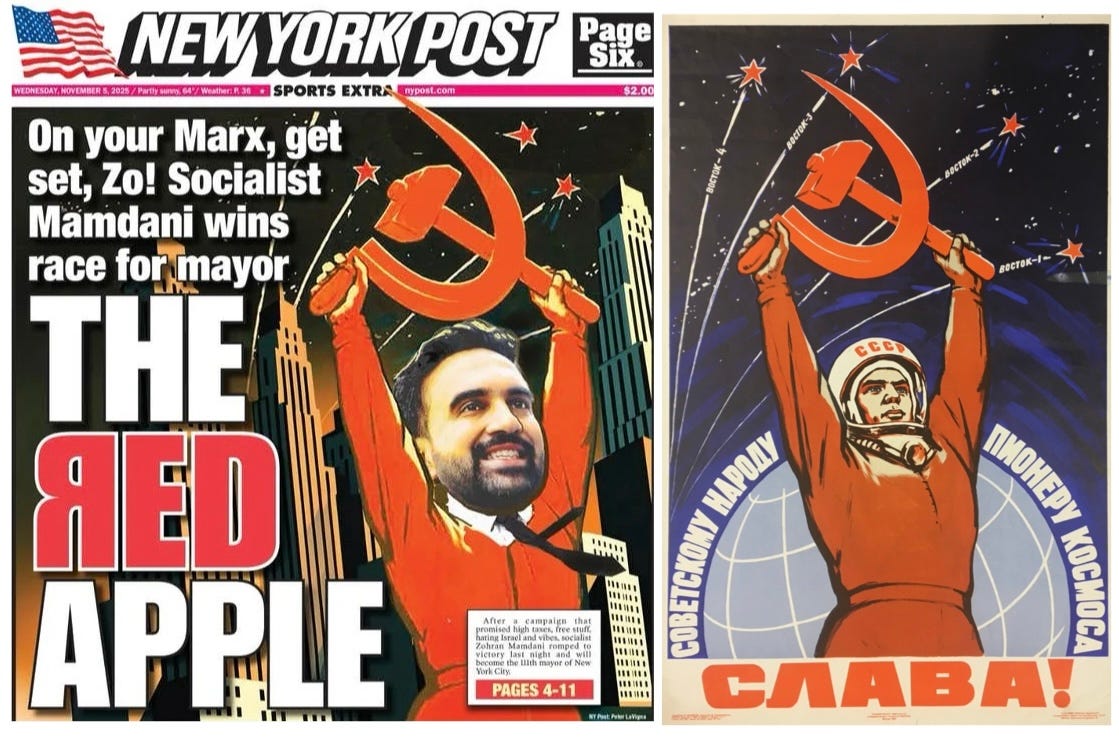

And if you need a reminder of what’s at stake here, this is Rupert Murdoch’s New York Post cover on the day after Mamdani won—and no, this is not a parody. The picture on the right shows the Soviet image that the Post’s designer stole it from. Because there’s nothing about ‘Open’ or ‘Inclusive’ that is good for Rupert Murdoch’s political or business interests.

Thanks to Ian Christie for sharing the Joxley post.

—Footnotes

1. My best explanation of why 40 years might be more than just empiricism is that it represents the two halves of a working life: the first when you pay your dues and get acculturated, the second when at least some people get to change the the things they hated in the first part. It’s worth noting that in their Fourth Turning model, Strauss and Howe propose an eighty year generational cycle that goes from crisis to crisis in eighty years, via a rebuilding stage, a stage where the benefits of rebuilding are enjoyed, and an unravelling stage—effectively positioning a mini crisis in the middle. As a systems model, it follows the same pattern as other models. But their timings of each phase, which go back to the middle ages, are suspiciously post-hoc, and the generational mechanisms they propose are unclear.

2. Our short term memory can hold 3-4 things in it, which is a good guide to the level of complexity that people can absorb when you explain concepts to them. Which is also why we write down shopping lists.

3. Ansell notes in a later post that the Labour Party had managed in policy terms to do exactly the opposite of what his data in recent posts would recommend. But then again, Morgan McSweeney is a political genius.

—-

An earlier version of this article is also published on my Just Two Things Newsletter.

Really interesting analysis, thanks. This makes sense of some of what I see at the protests at the local migrant hotel each weekend. FYI you’ve got the section on “a form of Conservatism that represented a light version of the Closed axis combined with some traditional support for more local businesses” twice, once in the “Political Energy” section and once in the “Ageing voters” section.