The tech newsletters I follow have been over-excited about NFTs, or “non-fungible tokens” for a while now, probably because it allows them to write about cool digital artists rather than decidedly uncool Silicon Valley bros. Me, I’ve been struggling with it a bit. Fortunately Alex Hern’s newsletter came to my rescue.

And just in time, since Christies has just sold an NFT digital work by the American digital artist, Beeple, for almost $70 million.

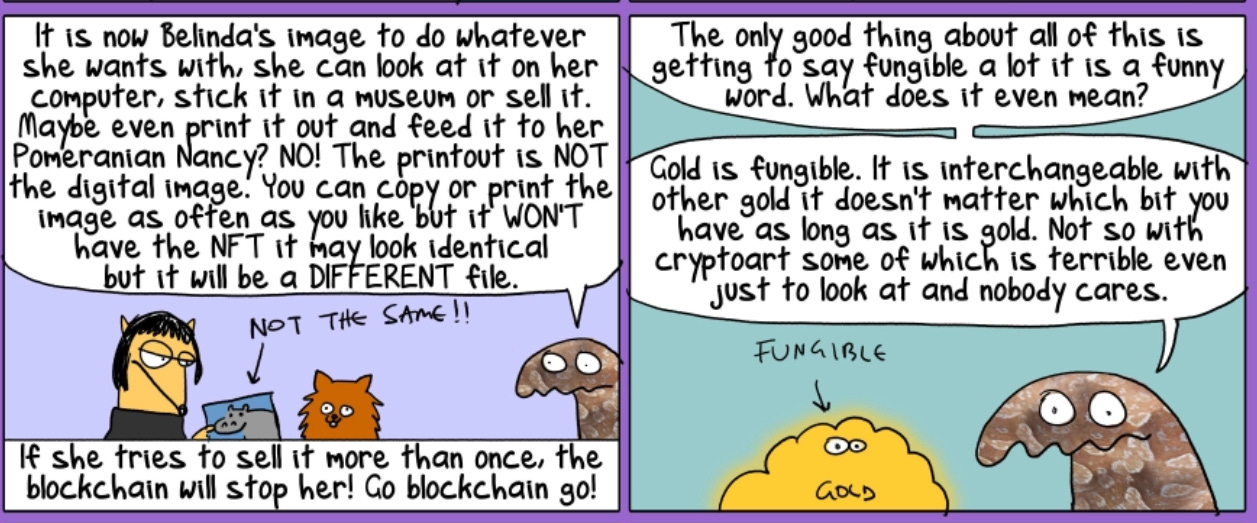

(If this is as much as you feel you need to know, the best rapid explainer is by the Australian cartoonist First Dog on the Moon, from which the image is taken).

(Two panels from the Last Dog on the Moon cartoon about NFTs)

Tokens

So let’s unpack the language first. The language about tokens comes from the world of crypto-currency. In terms of value, a fungible token has the same property as money, hence “fungibility”. If I swap a fungible token with you for one of the same value, nothing’s changed. We both still have the same store of value.

A non-fungible token, however, is unique. If I swap my non-fungible token with yours, we end up with something different. The first is not substitutable for the second. I’ve given you my Hockney print and have ended up with a Paul Nash. The reason that NFTs are all the rage is that by identifying the artist they allow the value in digital art-works to be identified and retained—including a cut for the artist when the work is sold on. Like the fungible tokens, though, the record of ownership sits in the blockchain.

In his article Alex Hern notes that the principle that sits behind this has been around for a few years now. There are some first generation NFTs that operate pretty much like trading cards. But:

the interest in the field has also expanded to protocols, including Zora and SuperRare, which aim to provide a more general service for creating and trading any digital asset imaginable. These are, for the most part, what people have been discussing in the last week or so: services which let you take, well, anything digital – a song file, image, poem – “mint” it as a new token, and then sell and trade it using, generally, the Ethereum blockchain.

All the same, the impulse behind this probably isn’t a vast cultural rush in the population but more likely loose money and loose time chasing a shortage of assets.

(Everydays: The First 5,000 Days, by Beeple. Source: Beeple)

Collecting

The work by Beeple sold at Christies is ‘The First 5,000 Days‘, a cumulative record of his practice since 2007 of producing a digital work of art every day. He seemed as surprised as anyone about the price it had fetched. But he’s clear that what the NFTs do is enable digital art to be collected. He told Elizabeth Howcroft at Reuters:

“Without the NFTs, there just legitimately was no way to collect digital art,” said Beeple, who makes irreverent digital art on themes such as technology, wealth and American politics… For NFTs, the artist’s royalties are locked in to the contract: Beeple receives 10% each time the NFT changes hands after the initial sale.

Hern suggests that this is a fairly narrow use case, since copyright is not contested in law, and is vested automatically in a work that is created, even in American law. But we’re not talking trivial sums of money: the all time sales volume of NFTs is $415 million, and art—at least before last week—represnted a quarter of that. And cryptocurrency lawyer Max Dilendorf told Reuters that he expected the whole art market to be digitised within five years.

Value

Put like that, it perhaps seems like an answer to a different problem; the way that digital platforms (think of Spotify) have squeezed the creators out of the value chain in cultural markets. This might be what the work of art looks like in the age of digital reproduction. Musicians such as Jacques Greene and Devendra Banhart are experimenting with NFTs that combine art and music, creating new value for music collectors. Put like this, it is perhaps like the limited edition of the 12″ single sold on coloured vinyl with a unique remix on the flipside.

And already we have seen some unusual cultural practice around NFTs. A group calling itself BurntBanksy bought a Banksy screenprint in a New York auction, transferred it to an NFT and then burnt it, moving the value from the physical piece to the digital domain. As with all forms of performance art, there is a video. It doesn’t burn quickly. Then again, given Banksy’s form in messing with the auction system, you can’t discount the thought that the group is just pranking the prankster.

There is probably an interesting piece to be written locating NFTs inside Walter Benjamin’s influential 1935 essay on ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,’ although I have neither time nor space to do this here. But in brief: it seems that they might complete the task of disconnecting the work of art from a location in time and apace, while reasserting its ‘aura.’ And, potentially, they might also reconcile the conflict that Benjamin identified between the cult value of art and its exhibition value.

Footprint

However, the elephant in the room for NFTs is their environmental footprint, which is vast. Hern summed it up like this:

No matter what you think the potential of the sector, it is inarguable that the current energy drain is out of whack with the current economic benefits. We’re talking “burn a lifetime’s worth of electricity to sell a digital edition of 1000 artworks.”

The French sculptor and climate activist Joanie Lemercier sold six NFTs in his first blockchain drop, and then discovered that his sale consumed 8.7 megawatt-hours of energy — equivalent to two years of energy use in his studio. Beeple has been working to offset the emissions from his NFTs, although offsetting has sceptics. Ethereum, the dominant platform, may be more energy intensive than alternatives. But this is certainly a live issue for many artists.

As Memo Akten told Flash Art:

Digital artists absolutely should be able to earn a living making the work they love. But this should not involve the immense footprint it does presently nor the current lack of transparency. New businesses and platforms must align with the values we are hoping to carry into the future.

A version of this post also appeared on my Substack newsletter Just Two Things.