I wrote last week, in my account of David Bent’s talk on business transition, that resolving the conflict within businesses between the short-run assumptions of finance and the long-run requirements of the transition is a critical issue. Moving businesses from being ‘time-blinkered’ to ‘long-minded’, perhaps. And this reminded me that I’d written about some of this in a client report a couple of years ago. Here’s a version of that with client bits taken out. It’s long, so I’ll break into two parts.

This conflict is partly an argument about the difference between 20th century businesses and 21st century businesses. They live by different metaphors. The metaphors of the first are about Newtonian physics and mechanical engineering. The metaphors of the second are about complexity, emergence, and ecological systems.

The formula of evolution

In one of the strongest statements of this argument, Eric Beinhocker argues in The Origin of Wealth,

“wealth creation is the product of a simple but powerful three-step formula—differentiate, select, and amplify—the formula of evolution.”

This understanding is not new. In the UK alone it can be traced back to management thinkers such as Geoffrey Vickers, F.E. Emery, Peter Checkland and Stafford Beer, all writing in the ‘60s and ‘70s. Apart from a universal trend in all disciplines towards complexity thinking—“the complexity turn” described by John Urry—there are three trends that have combined to bring this change into the mainstream.

These are:

(1) the long run shift to a services and knowledge economy, which places new demands on employees to bring their whole selves to work, even in low-paid jobs in retail or hospitality;

(2) the spread of digital and distributed technologies, which blur the edges of the organisation;

(3) the shift in values held by citizens and customers, from extrinsic public facing values to intrinsic personal values.

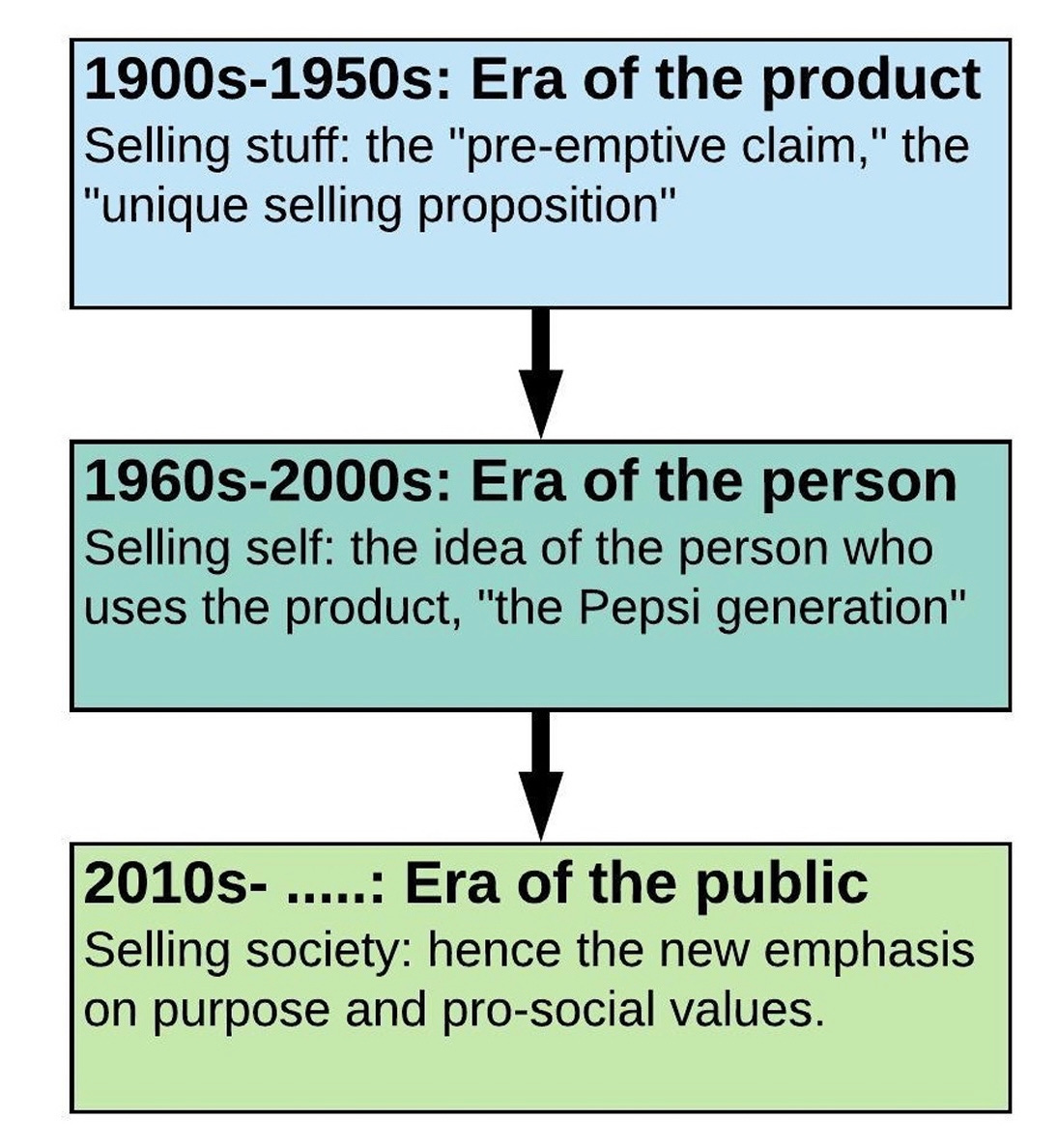

One consequence of this has been a transition in the world of brand and marketing behaviour. If brands responded to the ‘boomer’ generation by moving from ‘selling stuff’ to ‘selling self’, they are now ‘selling society’. My former colleague Walker Smith, says this is a ‘third era’ of marketing and branding, which he calls the ‘era of the public’. This means that businesses are now expected to have a clear view of their business purpose, although this sometimes sits uncomfortably with them.

(Source: J. Walker Smith, Kantar Consulting)

Complicated to complex

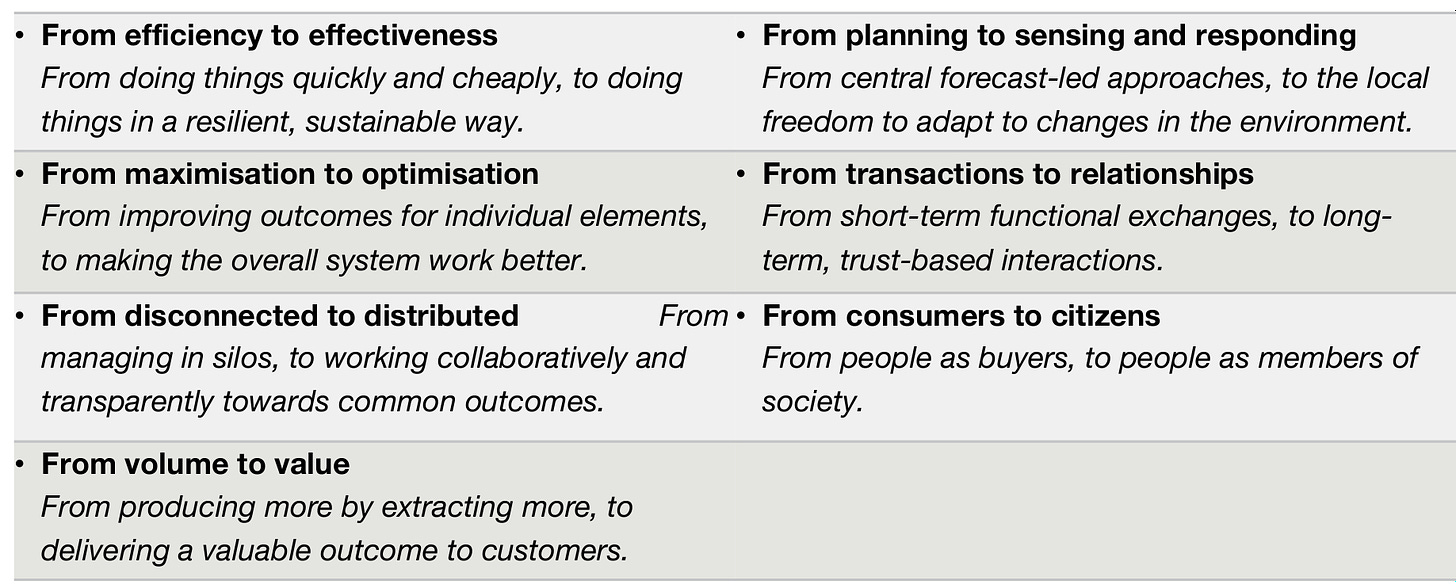

In turn, this means that the way we understand business is moving from complicated to complex. In a complicated world, cause always has the same effect, and parts are interchangeable. “Efficiency” is a metric of the complicated world. In a complex world cause and effect are inter-related and the outcomes of interventions are unpredictable. We’re still learning how to manage businesses in a complex environment. As the business writer Simon Caulkin says:

“Ecosystems represent a historic evolutionary shift in the ecology of business which offers vast potential for new kinds of value creation. But making the most of it requires an equal evolutionary advance in thinking about the form and functioning of the organisations that animate those ecosystems. The first law of systems is that everything is connected to everything else. The second law, obvious when you think about it, is that you can’t optimize a system by optimizing the parts.”

The table below, adapted from a report I wrote with Jules Peck a decade ago, summarises some of the directions of travel.

(Source: adapted from Curry and Peck, ‘The 21st Century Business’, The Futures Company.)

Companies are people

It’s worth stepping back a bit for a moment. Companies are people. The root of the word is in the Old French, compagnie, for “society, friendship, intimacy”. The Tomorrow’s Capitalism project has built on this to describe the different roles played by a company. Companies, it says, have five roles. They are: citizens; producers; customers; employers; and investors.

In theory, when these roles are aligned, then the organisation can move ahead purposefully. When they are not, you end up with what the economist Kate Raworth describes as a corporation with a split personality. Different roles—sometimes enacted by the same people—pull in different directions. For example, even when you look at businesses that have made significant public commitments to sustainability, you will usually find that many managers still have KPIs based on the volume of goods they are able to shift.

So the model of the emerging company needs to do more if it is going to be useful.

Connecting the company

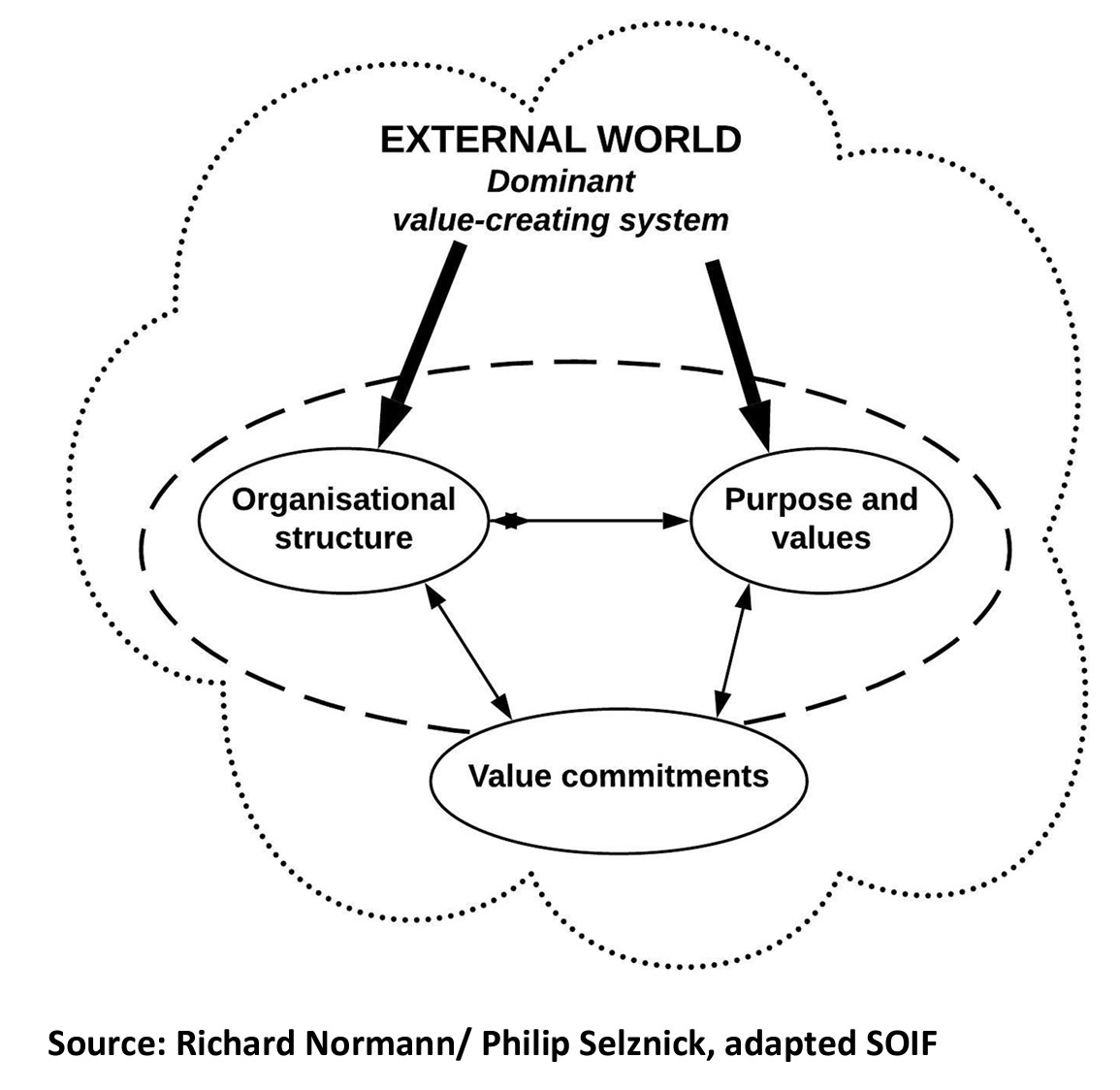

It needs to help us to understand both the roots of these kinds of internal conflicts, and the actions the businesses can take to resolve them. One way through this is offered by the management thinker Richard Normann. Drawing on the classic 1950s text Leadership in Administration, he proposes a model that connects different aspects of the organisation with the outside world.

The organisation has two touchpoints, in effect. One is with the business and economic institutions that frame what Normann calls the “dominant value creating logic” of the time. These include investors, of course, but also all of its exchanges with other organisations in its value chain or value network. The second is with customers, through its “value commitments”. Internally, these are articulated through the soft elements of purpose and values, and the harder shell of its organisational structure.

Value commitments

Value commitments are a way to create narratives about business purpose that involve having some kind of skin in the game. They also tend to be attacked if they are at odds with the value-creating logic. The role of a “value commitment” is as a concrete statement of intent that is designed to defend the company’s purpose and structure. But value commitments are also a way to move a company’s values forwards, to change expectations about the business. To give one example for the moment: Cynthia Carroll’s commitment when she was CEO of the mining company Anglo American to “zero harm” (no fatalities or serious injuries) was a value commitment, designed to improve Anglo’s safety culture. It was a concrete statement: people would be know if she had succeeded or failed.

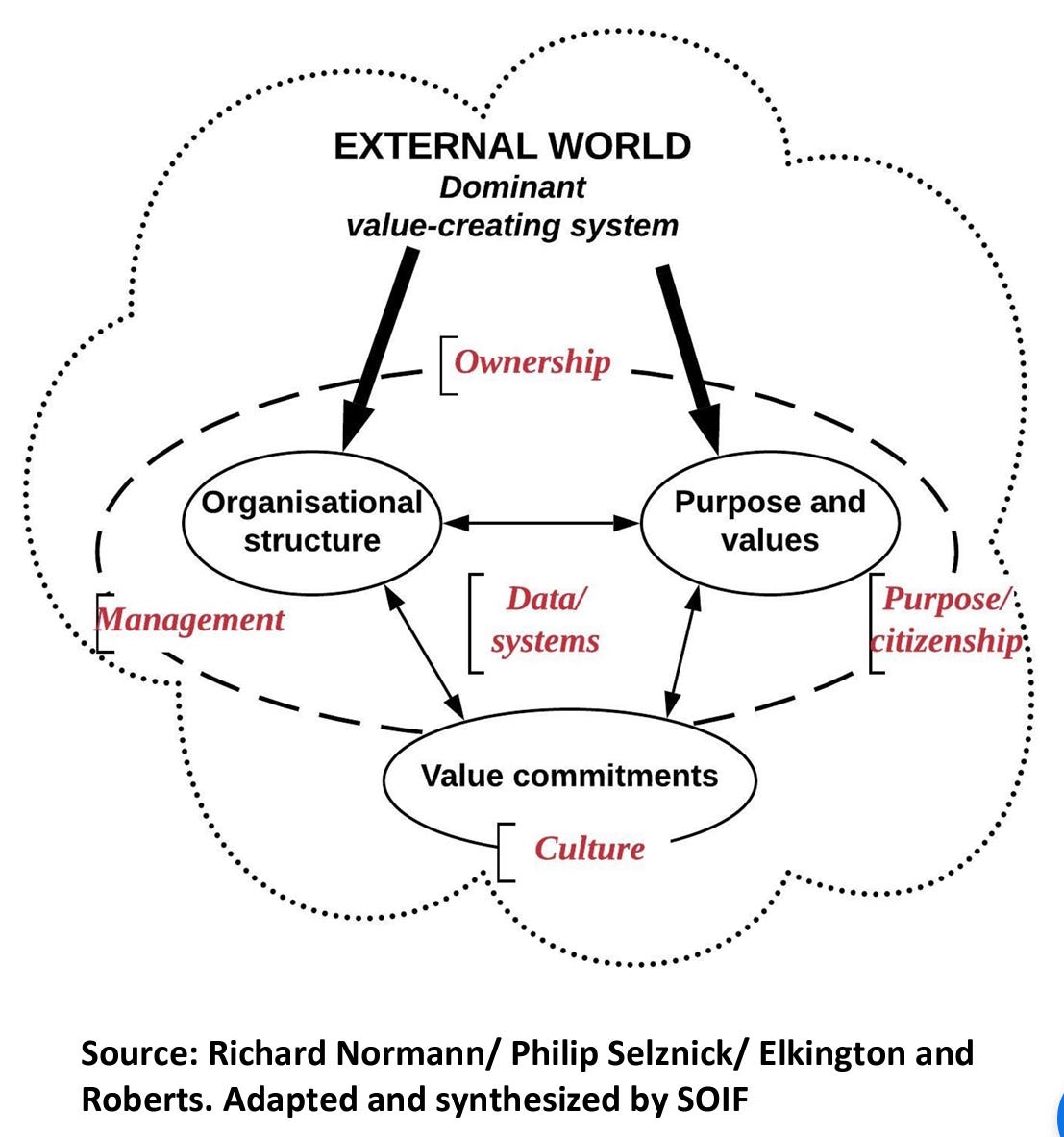

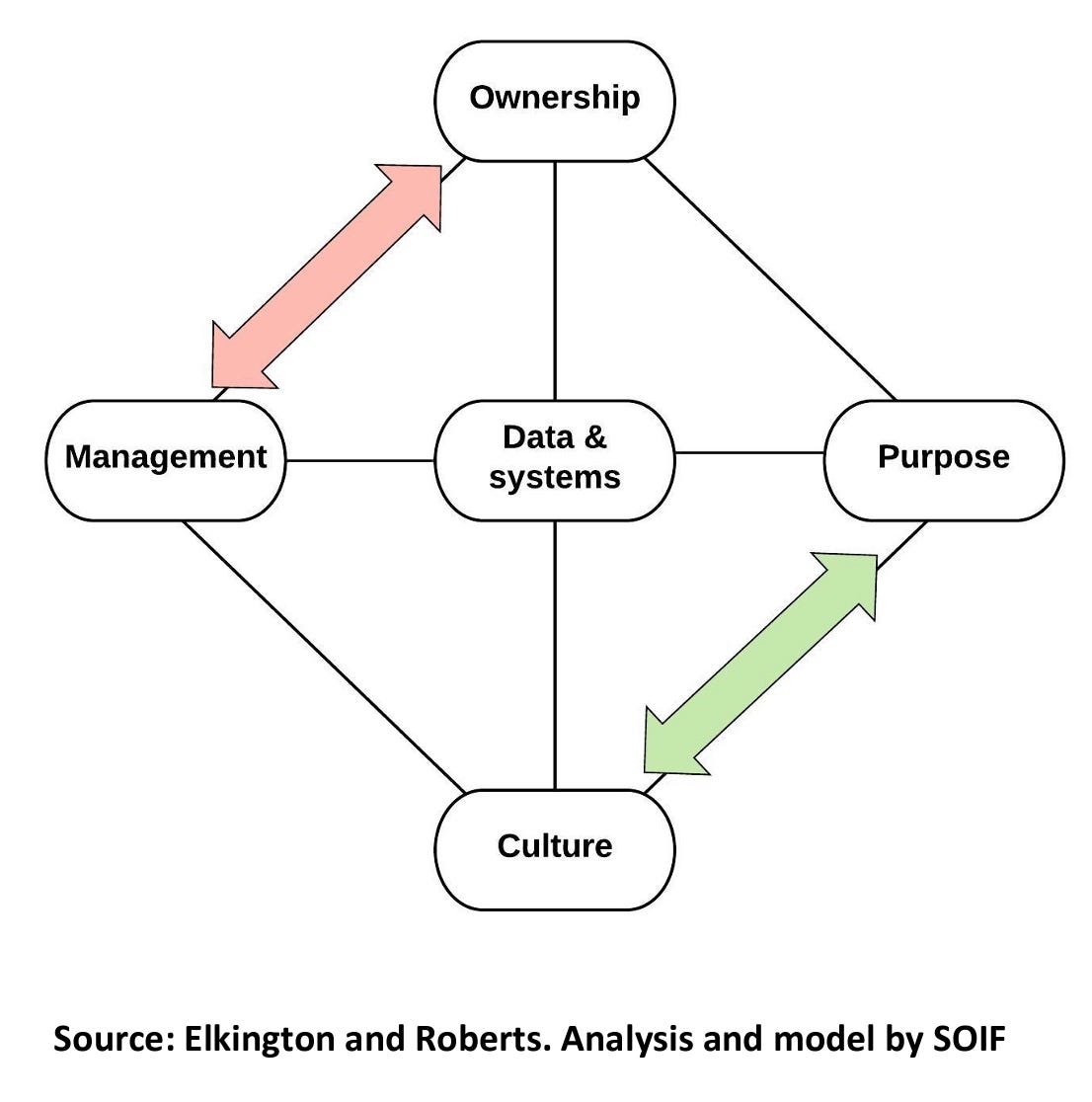

Today I’m going to build on all of this. Because this model has more value when different organisation functions are laid on top of it. Borrowing from and developing work done by the Tomorrow’s Capitalism project, one can simplify the organisation to five functions:

• Ownership

• Management

• Purpose/ citizenship

• Culture, and

• Data/Systems.

It’s also possible to map these five functions of the business back onto the Richard Normann diagram.

Ownership versus culture

In times of change, ownership and culture are likely to conflict with one another, and so is management and purpose. Similarly, ownership and management are likely to align as an axis that slows down change, while purpose and culture are likely to align as an axis that promotes change.

The reason for this is that ownership and management are both systems that are embedded in the business and its history. They are intended to be stable, and to provide structure, and this involves a degree of (partly necessary) “lock-in.”

In contrast, in times of change, purpose and culture are more fluid. They are rooted in values and attitudes, which change more quickly, and are also influenced more quickly by social change outside of the business. Data and systems, which are typically products of earlier “theories of the business”, and the assumptions embedded in it, sit in the middle of these tensions, evolving to fit new demands, always behind the curve.

‘Enacting’ the purpose

As a result, the value commitments that leaders and managers choose to make are critical and often symbolic. They are ‘enacting’ the culture and purpose they want to see.

The problems caused by current models of ownership is one of the recurring themes in the current literature about new forms of capitalism. There are good reasons for this, which I’ll come back to in a moment. But in the normal workings of a business, ownership should be an anchor on change. Shell’s research on long-lived companies, popularised by Arie de Geus in The Living Company, found that almost all of them were conservative about finance.

Similarly, the management and structure of a business is designed to maintain its integrity and ensure its continuing existence. All organisations are ‘dynamically conservative’ (in Schon’s phrase). They respond to shocks with the minimum amount of change needed to ensure their continuing viability.

Outmoded models

They therefore also tend to cling on to outmoded models of the world, and outmoded notions of viability. Even when actual data and performance elsewhere shows that these models are both wrong and no longer useful, they are reluctant to change. Businesses that are actively committed to change need to find ways to use purpose and value commitments to modernise structures and keep owners onside.

It’s worth exploring how this works in practice, with a couple of examples.

Food manufacturer Danone was founded with a mission that combined economic and social purpose. When its North American subsidiary acquired WhiteWave in 2016, it incorporated the combined business as a b-corps. This meant that it could enrol its social purpose in its legal corporate structure. This allows purpose to signal to ownership.

The company’s chief executive also told its North American executives that they would stop selling foods with GM ingredients in them. The management team achieved this in two years despite some initial scepticism about timescales.

Driving change

This represented a value commitment that used culture to drive change in management. But it doesn’t always work. It’s possible that Richard Browne’s attempt to move BP to “beyond petroleum” was a value commitment. But since it was backed by little in the way of meaningful action—not much in the way of “commitment”, in other words—it was read instead as greenwashing.

The legacy of the idea of ‘shareholder’ capitalism is that ‘owners’ have been privileged above other stakeholders. The combination of lightly regulated investment and digital technology has amplified the interests of owners, and created a financialised business sector.

The business literature is full of reasons why this is a bad idea. As Martin Wolf of the Financial Times observes: companies

“serve the interests of those least committed to it, while control is also entrusted to those least knowledgeable about its activities and at least risk of damage by its failure.”

Skewed incentives

In her book, Eve Poole quotes research that says in the age of high frequency trading, ‘owners’ own their shares for less than a minute, on average. A share conveys certain rights to the holder, but not the rights of ownership. This skews, hopelessly, the incentives in the market. It benefits short-termist financially driven businesses at the expense of others.

And as the economist Michael Pettis notes, it creates balance sheet incentives around debt that make it hard for prudent businesses to compete. It creates the conditions of predation.

Businesses that are trying to play by different rules—even large ones—can’t escape from these dynamics. Again, looking through the model at a well-known example, the short-lived bid by Kraft Heinz for Unilever is a case in point.

The costs of predation

Kraft Heinz, owned by 3G Capital, has an aggressive M&A driven model which squeezes costs out of acquisitions and returns money to shareholders. It seems to produce short term improvements in returns and a long-term decline, which should be to no-one’s surprise.

Unilever’s model was about long-run, purpose-driven growth. But facing down the bid wasn’t a cost-free exercise. The price of getting shareholders to support the Unilever Board was a a share buyback and more aggressive cost-cutting—both classic behaviours of ‘financialised’ companies. At the time of the bid, Unilever’s long-run share price growth had been comfortably greater than that of Kraft Heinz. But both these measures would reduce growth. When ‘owners’ meet ‘purpose’, in the current model, ‘owners’ win.

Broadly speaking, this all comes back to a case for different rules governing the intersection of finance and businesses. The joint stock company—a creature of the early stages of modern capitalism (effectively dating in the UK from 1844)—is, in the way that it is currently constituted, no longer fit for purpose. In an age of instantaneous share transactions, companies need a buffer to protect them from what amounts to hot money. The thinking behind B-corps is one way to create that buffer—purpose, in effect, gets written in to the company’s legal articles of association.

But on its own, this is not enough. We need to change the rules of finance. I know that there are people working on this who know much more about it than I do. I’d love to hear from you.

—-

A version of this article was originally published in two parts on my Just Two Things Newsletter.