I was doing a little bit of picture research the other day, and I came across an article about illustrations from the 19th century imagining the long term future. I know quite a lot of these images—I often use them when I’m doing futures learning as a warm up. In particular, in late 19th century France there seemed to be a lively market in images of the year 2000, for reasons I’ve not yet managed to understand.

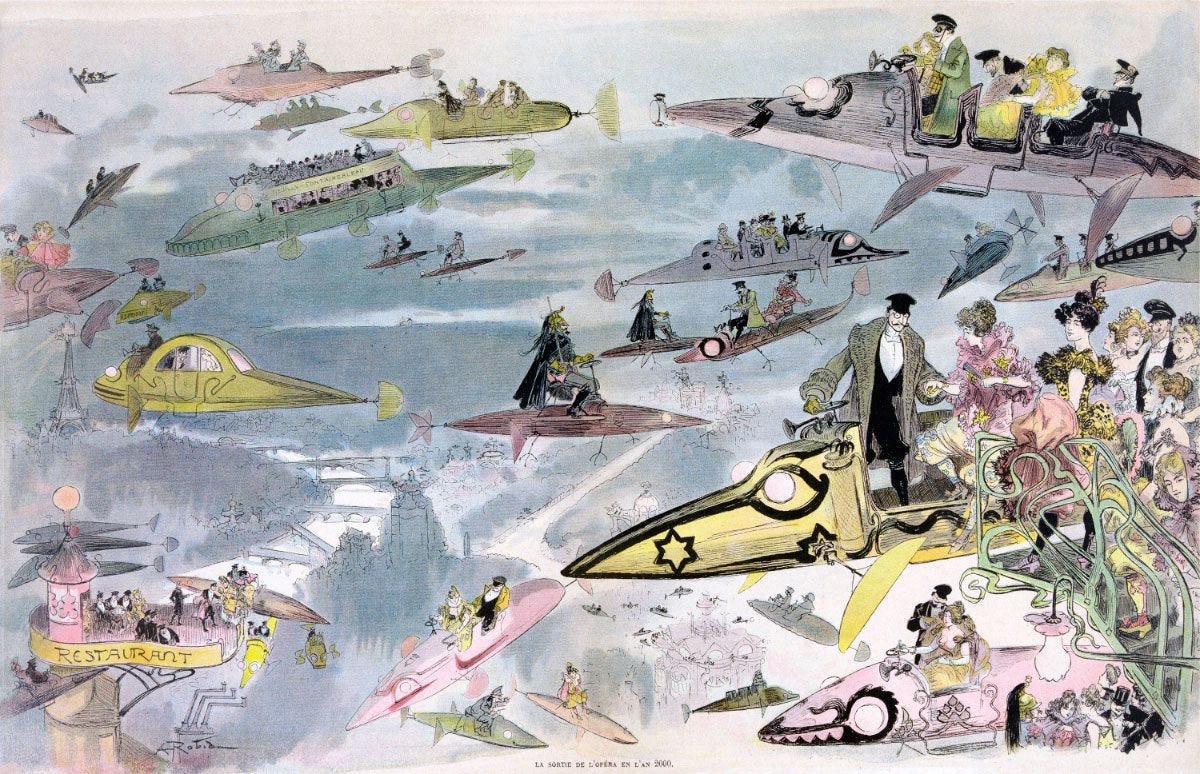

One of the leading French artists was Alfred Robida, who was interested in both the future in the air and also audio-visual communications. Here’s his ‘Leaving the Opera in the Year 2000’.

Submarines

What intrigues me about this image is the date: 1882. At that time, the only aerial objects were hot air balloons, but the French Navy had developed a powered submarine 20 years previously, which might be why these flying machines look a bit like submarines. When I talk about this image, I remind people that it’s possible to imagine future technologies even if they aren’t yet able to build them.

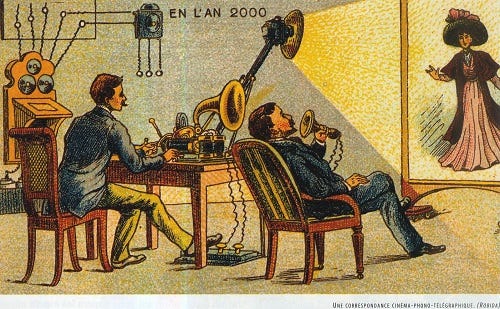

It’s not included in the article, but Robida also has a well-developed line in audio-visual futures.

There’s a projector showing the a woman on screen who is being talked to through a telephone. Alexander Graham Bell had invented the telephone about five years ago, but the cinema was still 15 years away. All the same, there were a lot of 19th century visual technologies that created the idea of visual movement.

Fin de siecle

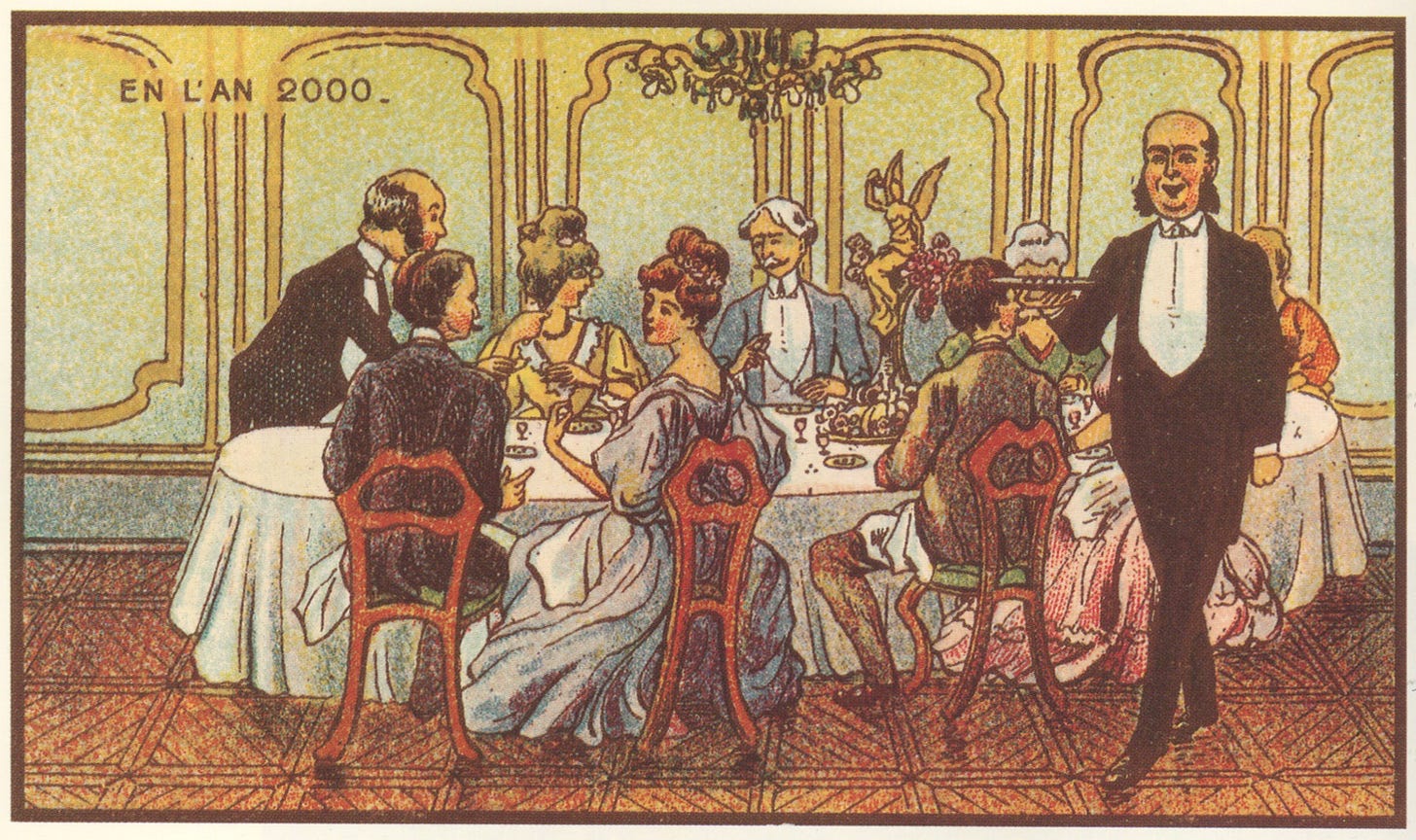

There’s a similar set of ‘year 2000’ photos developed by Robida’s French near-contemporary Jean Marc Côté, published in 1899. Flight appears in these—a flying rural postman, a helicopter—but there are various other technologies at play here as well. We have these images more or less by chance:

In the early 1920s, a set of 100 postcards were discovered in an abandoned French factory basement, amongst shelves of dusty novelties and circus automatons. From there they sat in an Editions Renaud, a Parisian antique shop for over half a century, until they were bought in 1978 by author Christopher Hyde.

They had been commissioned by the manufacturer Armand Gervais to mark the “fin de siècle festival” of 1899. Here’s one that seems to be an early version of the “food-to-pills” futures trope that reappeared endlessly through the 20th century.

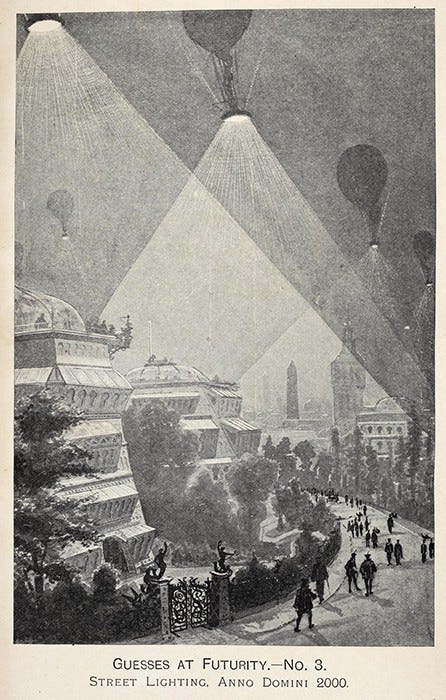

Lighting

One of his other 1899 images has a front room being heated by radium, discovered the previous year. This was before we discovered the side-effects, of course.

An English image from the same decade combines uses aerial technologies to solve a big urban problem of the time—that the streets were dark at night. This is by Fred Jane in Pall Mall Magazine, and I like the honesty of the title: “Guesses at Futurity”.

Some of the future images in the article are intended satirically. I hadn’t come across the work of the American illustrator Harry Grant Dart before, for example:

He was also a cartoonist for Life and Judge magazine, where his satirical cartoons were less optimistic than many of his futurist contemporaries, channelling anxiety and paranoia about where technological change might lead. “We’ll All Be Happy Then” shows a mishmash of devices designed to enhance our domestic life: stored sunlight overhead, fresh air pumped in from the Alps, opera delivered to your speaker, 24-hour news with “events as they transpire, accurately recorded.”

Human knowledge

From much earlier in the century, the cartoonist Willian Heath similarly satirised the industrialist Robert Owen’s description of “the march of the intellect”, intended to highlight the big strides being made in human knowledge at the time:

His excitement was openly lampooned in a series of prints by William Heath: with mocking enthusiasm, Heath depicted a plethora of future transport methods, including steam horses, vacuum tunnel transport from London to Bengal, flying mail carriers (which would become a futurist trope), and Irish immigrants being fired from a giant cannon (reflecting topical social prejudices).

Vacuum tunnel transport? Anyone would think that Elon Musk had got his futures thinking from William Heath. Robert Owen probably didn’t deserve Heath’s scorn, since he was a progressive industrialist who used technology to improve the circumstances of his workers. All the same, one of the things I took away from the article is that we might benefit from some better satire these days of some of the more self-serving future visions of our business and political elites.

And of course, one of the striking features of all of these images is that in the future, the technology changes, but the clothes and social relations remain frozen in time. But that’s always much harder to imagine.

—-

A version of this article is also published on my Just Two Things Newsletter.