This is part of an occasional series here on methods that I use in my facilitation and workshop design

A method I sometimes use to deepen my understanding of what’s going on in the H2 (second horizon) space of a Three Horizons map is a version of Eden and Ackerman’s ‘power and interest’ grid.

It helps you to understand what is happening with the different actors involved in the second horizon, and those that are relevant even though they seem uninvolved. And, therefore, it gives insights into the kinds of things you might be able to do to change the landscape.

I’d first used the power and interest grid in this way in the early 2000s, as a way of exploring a set of scenarios that also seemed to have a complex set of relationships between the actors.

Stakeholder mapping

The power and interest grid wasn’t actually intended as a method of actor analysis. In Eden and Ackerman’s book Making Strategy—a book I like—it was introduced as a way to structure and therefore simplify stakeholder mapping. At the time (1998), this was an underdeveloped area. Here’s an extract from the book:

In undertaking a stakeholder analysis, it is usual to focus attention upon a large array of actors who have an interest (stake) in the strategic future of the organization, whether or not they have significant power in relation to the organization. Indeed, as we discussed above, stakeholder analysts often make a plea for the specific inclusion of disadvantaged and powerless groups – the analysis being driven by a value-laden, rather than utilitarian, view of the role of stakeholder analysis. In contrast, our own concern with stakeholder analysis has a strictly utilitarian aim of identifying stakeholders who will, or can be persuaded to, support actively the strategic intent of the organization (p120).

Static picture

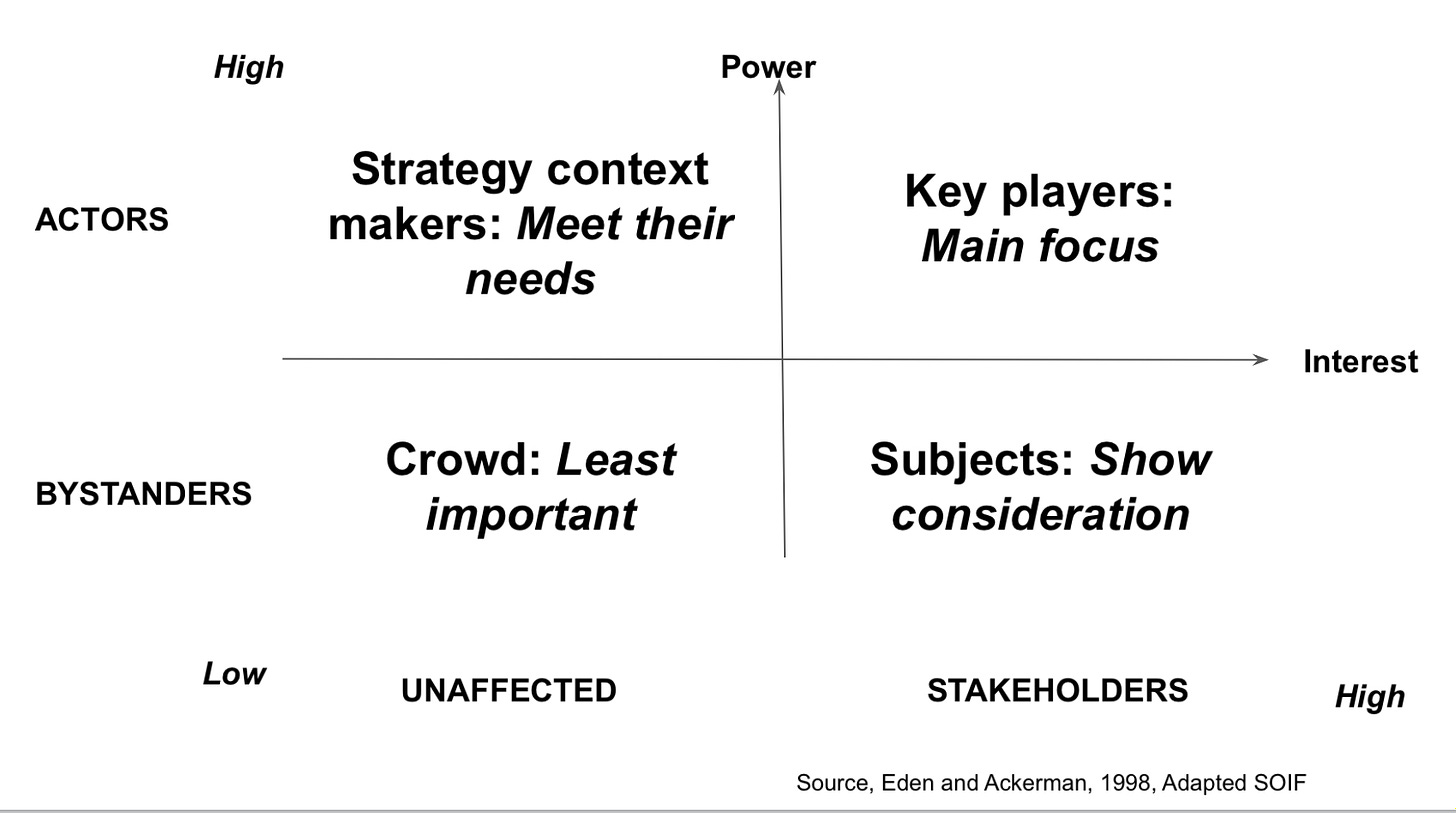

Hence their focus on interest and power. In their version, interest comes first because part of their simplification process is to weed out groups that you don’t need to worry about. And if your interest is in stakeholder management, this leads you to a chart that looks a bit like this. (Note that in their version, because they’re only interested in this as a stakeholder mapping matrix, interest is on the vertical axis and power on the horizontal. I’ve transposed the axes here because it makes ‘power’ more visible).

But: this is a pretty static picture. You can see it working in partnership with the classic comms RACI matrix, but it doesn’t help you think about actor dynamics. It’s also true that there aren’t many tools in the futures cupboard to help you think about actors. The most detailed one is the MACTOR method, was developed by La prospective, which has been explained by Michel Godet in a couple of places: it’s part of a long and technical paper by Godet in Futures Research Methodolgies V3.0. But, as he says, it takes several months to do it well.

Actor interaction

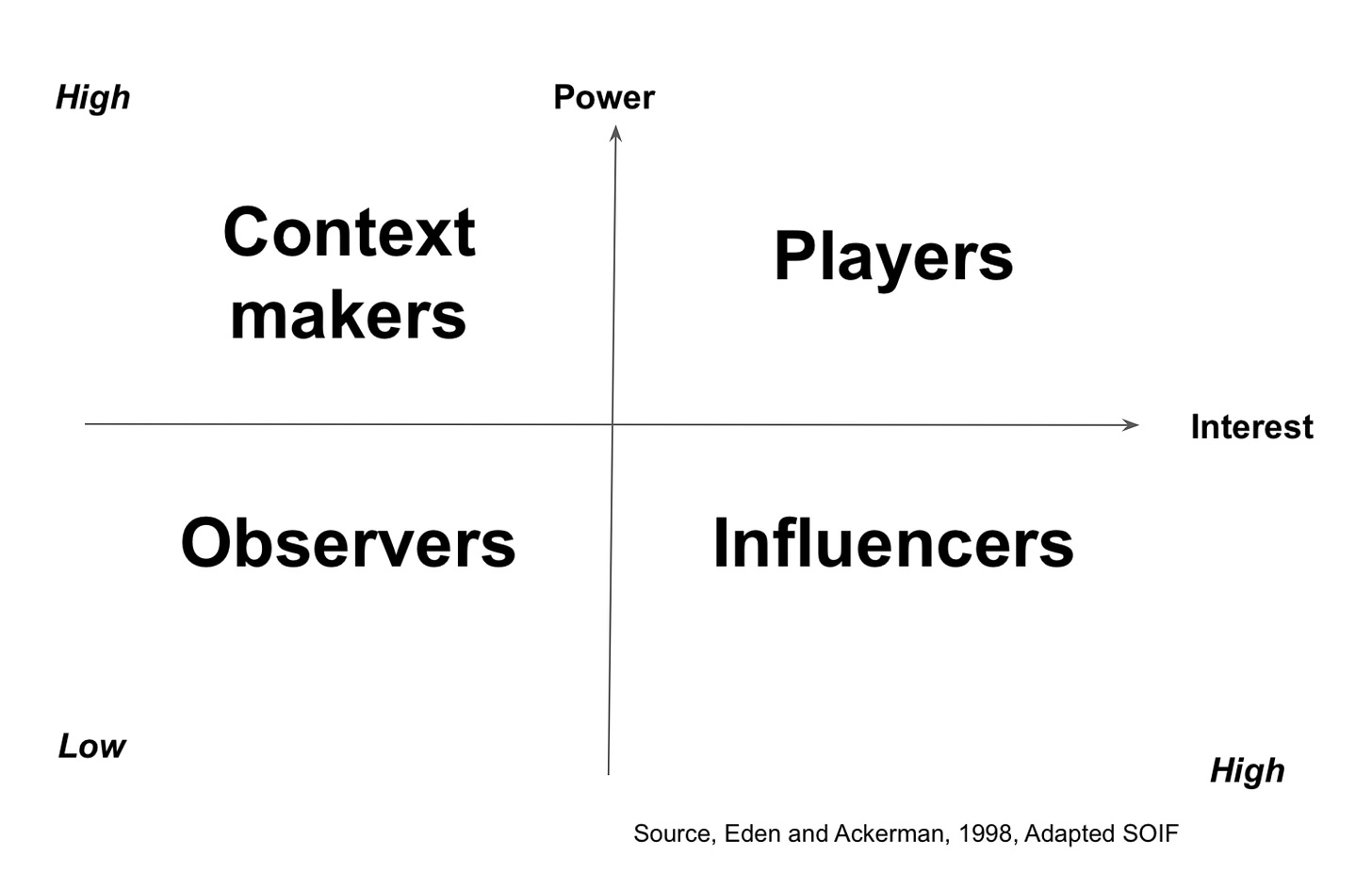

Hence the attraction of adapting Eden and Ackerman’s model as a mapping model as a way of analysing actor interactions in a landscape. The actors still look much the same, but the labels are a bit different.

The Players in the high power/high interest box in the top right are usually fairly easy to work out. The questions here are about financial resources and commitments, political or regulatory authority, about understanding incentives.

Often the Context Makers (high power/low interest) are overlooked, but if you’re trying to change a system, this isn’t about “meeting their needs”. The organisations in this space are typically either financial (in the UK political system, the Treasury is always in this box, which is one of the reasons why the UK system is dysfunctional) or they have responsibility for an overall legal framework of which the system in which you are interested is only a small part. Often the questions here are about rule-setting, and—in terms of change—about re-framing.

Understanding influencers

Usually the people I work with are in the Influencers box, and in practice they are often both the most interesting and the most dynamic actors in the system, precisely because they are the people who are trying to make change happen. They are—in terms of Molitor’s S-curve—busy “advancing” some new policy ideas.

The questions here are about who is campaigning, and who is lobbying; what kinds of arguments they are using; how those arguments are being framed; what kinds of alliances they are making; and whether they are changing the perceptions of the Observers.

Because: if you can increase the salience of your system to the Observers, the system starts to work in different ways. This is a communications space, largely, about touchpoints, narratives, and mobilisation.

Dynamic map

The important thing isn’t just to catalogue the actors on the grid. It is also to map what they are trying to change, and how they are trying to do it. What you’re trying to do is create a dynamic map of the points of change and the strategies being used to achieve it.

When I first used this in the 2000s, the examples that I used were from the world of sustainability in the UK. Looking at this from the point of view of the Influencers, there were different strategies. The World Wildlife Fund was choosing to be an adviser to organisations in the Players space, effectively to get access to the ‘top table’, even as they were accused of greenwashing their partners by other organisations. Some of the influencers built joint campaigns and coalitions, creating—they hoped—enough mass to move themselves up into the Players space.

The RSPB (Royal Society for the Protection of Birds) used mass marketing in the 1990s to build up a membership of several million people, effectively moving Observers into the Influencers space, and it used the money from these members to buy large amounts of land for conservation, although it got criticised for this. But similarly, when it came to conservation issues in the UK, this moved it into the Players’ area.

Changing the context

One more story: A bit later on I met a public infrastructure manager who was trying to refurbish his infrastructure sustainably. He was told (‘Context Making’) that he could only procure this at lowest cost, which meant that it wouldn’t be sustainable. A bit more legal work, and he was advised that ‘lowest cost’ could mean ‘lowest lifetime cost’, at which point the sustainable bids were much more competitive. This is more about ‘changing the rules’ than ‘meeting their needs’.

I have typically used this in public multi-stakeholder projects and ‘futures to policy making’ projects. It works in these. I don’t know yet where it doesn’t work.

—

A version of this article was also published on my Just Two Things Newsletter.