Every so often when reading an obituary of someone, or an awards citation, you realise that you have internalised their work into your thinking without having read it directly. So it was with Donald Shoup, the California transport academic who spent his life working on the problem of urban parking, and who died in February.

His sometime teaching colleague M. Nolan Grey has a long piece celebrating Shoup’s work at the Works in Progress newsletter.

The problem of urban parking is this: cars are only used about 5% of the time—that’s approaching an hour and a quarter a day, so in many cases that number is likely to be too high—and the other 95% of the time they have to be stored somewhere:

When Americans first started buying cars en masse in the early twentieth century, the solution seemed obvious: park them along the curb. In the most radical shift in city planning in human history, urban streets—once the site of gathering, selling, and playing—were redesigned around moving and storing cars.

And frankly, this has been so normalised for us now that it is possible to forget how strange it actually is. Here’s a photo from the first part of the 20th century—before there were cars everywhere—of a street near where I live in London. It’s noticeable how much more spacious it seems here than it does today when it is cramped by lines of parked cars along both sides.

Parking is too cheap

But these days, in contrast, our cities and towns are dominated visually and physically by parked cars, almost everywhere you look.

Shoup’s insight seems simple, but in a world that had normalised car use, it was radical:

parking is nearly always too cheap.

This situation had come about slowly. As car ownership started to increase, people parked on streets because it was free to park there, and it took a long time to fill up this space. But once car ownership became a mass phenomenon, the problem of parking cars became a significant land use problem.

Off-street parking

In the US, which experienced the problem first, planners responded in many cities by imposing minimum off-street parking requirements in new buildings, increasing the cost of housing significantly.

Grey has a calculation in his article about the effect of this on even modest urban housing, which now needed to incorporate an off-road parking space into its design. It adds anything from $20,000 to $80,000 to the cost of the housing, depending on whether the parking space is at surface level or below ground, and may also make impossible the renovation of older buildings, and infill development to increase density.

There’s a chart in the article of Houston’s extensive rules on offstreet parking for different kinds of developments. They are based on an influential document by the Institution of Transportation Engineers, the Parking Generation Manual. But Grey suggests that this is “pseudo-science”:

At first blush, it seems very scientific, replete with charts, numbers, and statistical jargon. But the typical estimate in the Fifth Edition is based on fewer than 10 observations, often with no clear correlation.

Land take

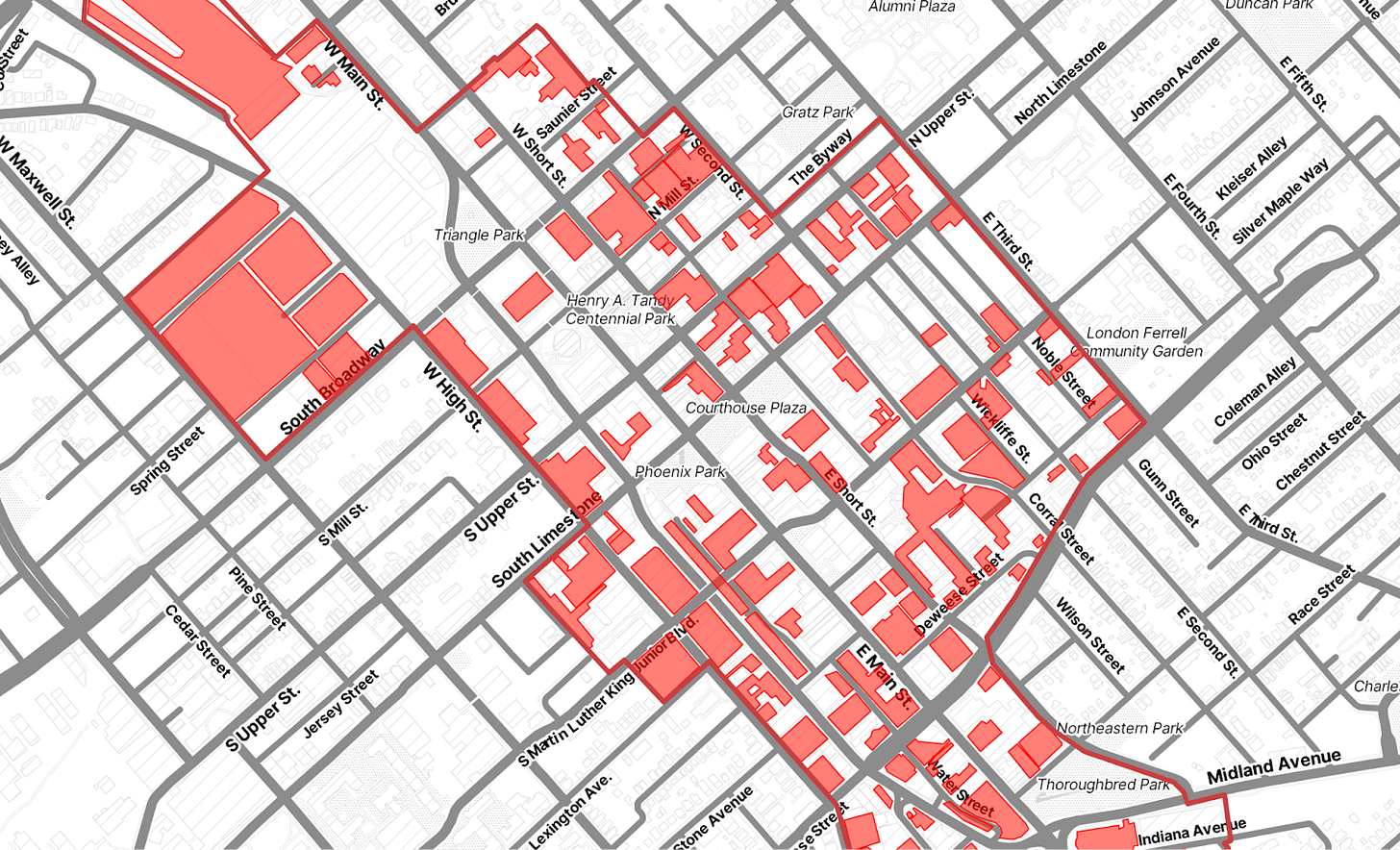

The space given over to car parking in downtown areas also increased. Grey has a chart in his article showing the land take of car parking in downtown Lexington—about 38% of the total, marked in red on the map.

Some of this was deliberate policy. I’ve recently read Robin Robertson’s fine novel-length poem The Long Take, which unfolds over a decade or more in post-war Los Angeles. One of the narrative threads is about the way in which the old downtown residential area was systematically demolished by the city authorities to make way for freeways and car parks.

Down 3d to Main: houses boarded up, stores

with their windows soaped over, signs saying CLOSING OUT SALE.

Breaks in the street where buildings had been,

being cleared for parking lots.

A note at the back of the book explains that the CRA [Community Redevelopment Agency] which ran this process, was

[u]naccountable and largely corrupt [and] in thrall to the business community and the automobile industry. They demolished most of the old and historic residential buildings in downtown Los Angeles either to make way for freeways or for lucrative street-level parking.

Cruising the streets

Free parking also has more immediate day to day effects. Because services that are free are usually over-subscribed, it leads to people cruising the streets waiting or hoping to see a car pull out of an empty space. Some surveys estimate that a third of drivers in an American downtown are cruising for parking:

If we could flip a switch and reduce traffic by 30 percent—with all the attendant costs to air quality, street safety, honking, wasted time, and street damage—we would almost certainly do it.

The effect of all of this is to bake in an over-supply of car parking, and to transform the urban environment so it is dominated by the car:

In neighborhoods built before the car, they made a wave of demolitions legally necessary. Today, over a third of the typical American downtown is now taken up by surface parking lots—and that’s before considering parking garages. In the suburbs, built out consistent with these rules, the result is a landscape of garden apartments, strip malls, and office parks surrounded by acres of parking lots that are virtually never full.

Managing demand

Shoup’s challenge to all of this came in a vast book, The High Cost of Urban Parking, published in 2005. It argued, at length, that free parking was never free because of all of the costs that came with it. It also suggested that trying to regulate the problem away by increasing the supply of parking was looking at it from the end of the telescope.

It was more efficient to manage demand for parking by pricing it properly. If there was too much demand for parking (as seen in drivers jostling to find parking spaces), it was because parking wasn’t expensive enough.

Shoup had had this insight as “the token economist” in UCLA’s Planning Department:

If you set a high enough price, at least one spot will always be available. Nobody will have any incentive to waste their time cruising. Better yet, if prices can fluctuate in response to demand, drivers will be incentivized to adjust their trips efficiently. Those with options could instead take the bus, minimize driving at peak times, or park a little further away and walk the rest of the way.

In fact, people had been trying to price parking, in fits and starts, at least since Carl Magee patented the coin-operated parking meter in 1935. But the politics of getting people to pay for something that used to be free is always tricky.

Sharing the revenues

This was one of Shoup’s critical insights. If you hand some or all of the parking revenues over to districts, the politics changes:

If you take curb parking revenue and invest it in conspicuous local improvements, such as street trees, repaved sidewalks, or regular street sweeping, locals will not only support pricing curb parking—they will often demand it. Once a parking benefits district is established, the politics of pricing curb parking will be secure, and planners can remove minimum off-street parking requirements without fear of backlash.

And although some of the issues I’ve discussed in this article are more skewed to the United States, this issue of getting people to pay for parking—and by extension to pay a fair price for car use, given its external costs—is still a problem everywhere.

The manual

The book wasn’t released into a vacuum either. Shoup had spent several decades training transport planners. What The High Cost of Urban Parking did was to give them the manual.

Shoup was hardly the model of a rock-star academic. Grey describes “a stuffy academic straight out of central casting”—tweed jacketed, bearded, cycling into the office. But unlikely as it seems, given his persona and his subject, he’s given his name to a transport movement: shoupista.

And the shoupistas are winning in the US at the moment. Cities are pricing parking, and abolishing off-street parking rules, slowly, to be sure, but steadily.

Important and neglected

Grey has some thoughts on why Shoup was effective. He picked a topic that was “simultaneously important, tractable, and neglected”, on which planners had quite a lot of agency, and which was largely neglected.

Second, he found a way to reframe the policy problem of free parking so it appealed to people with different political perspectives:

Are you a conservative? People should pay for the services they consume. Are you a progressive? All this unnecessary driving can’t be good for the environment. Are you a libertarian? Clearly, the solution to scarcity is prices and markets. Are you a socialist? Let’s stop privatizing the public realm by turning it into a free parking lot.

Third, he kept telling the same story. He stuck to parking, rather than diversifying into other issues.

Rolling up his sleeves

Fourth, he built the next generation, training them at UCLA. And more:

Shoup eagerly responded to emails from planners in even the most unremarkable small towns and often helped young scholars to co-author some of their first research on parking. In his seminars, students were encouraged to publish their work via op-eds or academic papers.

And last, when there was a parking issue to campaign for, he rolled his sleeves up and got involved, working with people to lobby for good policy.

Maybe there’s some broader lessons here.

This short TL:DR animation actually features the voice of Donald Shoup explaining his ideas in a nutshell, and has a good punchline.

H/t to Peter Curry for the link.

—

A version of this article was also published on my Just Two Things Newsletter.

Andrew, am from Ahmedabad (the city of the recent plane crash), India. Parking is a subject that occupies a lot of my mind-space too :). The situation’s quite bad here in my city and in all reasonably big Indian cities, and even in small towns.

Am fighting a legal battle in which parking is the key issue. I am recording some bits of this journey on my X/twitter handle Parking Chor (Chor = Thief / Robber), and also on Youtube by the same name.

Thank you for introducing me to Donald Shoup’s work. Will be exploring his work keenly.