I am one of the thousands of people who have migrated away from Twitter since Elon Musk took over. I have a new identity at the federated social media site Mastodon: I haven’t yet deleted my Twitter account, but the main question at the moment seems to be whether it will go bankrupt or collapse before or after I do that.

An entertaining site called ‘Twitter is going great’ is monitoring all the ways that Musk’s management of the site is not going great. At time of writing, one of the the top stories there is that around 75% per cent of the remaining Twitter employees have responded to Musk’s ‘stay or go’ deadline by declining to stay.

One of the big questions about Twitter at the moment is this: it’s hard to tell whether Musk’s behaviour is driven by malice, mishap, misunderstanding, or miscalculation. This distinction perhaps won’t matter much to the thousands of people who have already been laid off from the business (and in some cases chaotically rehired). All the same there’s evidence for all four.

Mishap

If mishap, it’s probably caused by misunderstanding the nature of the business. Whatever problems Twitter had weren’t caused by engineering: basically, it’s an unprofitable media company with some tightly defined regulatory restrictions. I’m aware that the response to this is sometimes something along the lines of “Musk billionaire genius Tesla SpaceX blah blah blah blah”, but Tesla and Space X are very different businesses. Specifically they are both in sectors where engineering innovation that drives down costs is of strategic value; and where substantial public subsidies or support have been available.

So all that initial noise about Musk getting engineers to show him the code they had written recently was wasted effort. Certainly watching some of Musk’s posts over the past week has been like watching someone doing Social Media 101–or even the introductory course before that—in real time with a real social network.

Miscalculation

In the miscalculation camp it’s hard to imagine which financial genius though it a good idea to buy a company with less than a billion dollars a year in cash flow and then load it with debt that costs a billion dollars a year to service. Or then decided that alienating advertisers would be a good strategy. This surely deserves some kind of investment banking Darwin Award.

Either way, the attempt (now paused) to use the sales of “blue tick verification” at $8 a month to help fill this gap is definitely going well.

Misunderstanding

On misunderstanding, it’s now clear that one of the reasons that a swathe of senior staff left the organisation last week was because Musk didn’t understand the seriousness of breaching the Federal Trade Commission’s Strict Consent Decree. The consent decree dates back to a massive data breach in 2011, but more saliently, the FTC also issued a substantial fine to Twitter earlier this year for violating it, and also tightened up the order. How serious is this? The employees concerned didn’t fancy the possibility of going to jail, as Techdirt reported:

According to the Verge, Elon and his entourage have made it clear that he doesn’t give a fuck about the FTC… So, here’s the thing. While Elon may think he’s not afraid of the FTC, he should be. The FTC is not the SEC and the FTC does not fuck around. Violating the FTC can lead to criminal penalties. I mean, it was just a month ago that Uber’s former Chief Security Officer was convicted on federal charges for obstruction against the FTC. And you wonder why Twitter’s Chief Security Officer resigned?

One of the implications of the Consent Decree is that it simply isn’t possible to rollout new product features rapidly, because they need to be reviewed for privacy implications. In the same vein, the Twitter legal department’s decision, post-Musk, that engineers should ‘self-certify’ compliance with FTC rules and privacy laws, also breaches the consent decree. (Later on, someone mailed Twitter staff on Musk’s behalf to say that Twitter would abide by the Consent Decree).

Malice

On the evidence for malice: Saudi money, the strong “free speech” statements that were rightly read as a code for opening the floodgates on hate speech, firing chunks of the content moderation teams and all of the Human Rights team, the mid-term elections tweets last Monday and Tuesday recommending voting Republican, promoting conspiracy theories about the Pelosi attack, are all evidence. It says something when a campaign involving advertisers is called #StopToxicTwitter. (Yes, there’s also a hashtag).

We won’t know for a while which of these it is, or which combination of them. It may be the arrogance of a billionaire surrounded by yes-people. But social networks do die—they just usually die a bit more slowly.

Reasons to leave

One of Musk’s problems here is that he has given his users enough reason to look for alternatives, and put up with the pain of the learning curve. Gareth Edwards (aka ‘John Bull’) had a memorable thread on the social media site—pretty much the last thing he posted before he left it—on the idea of the Trust Thermocline.

The idea of the Thermocline is having a bit of a moment. On his Roblog Rob Miller used the same idea recently to discuss the relationship that organisations have with the truth. (Meaning something like ‘ground truth’).

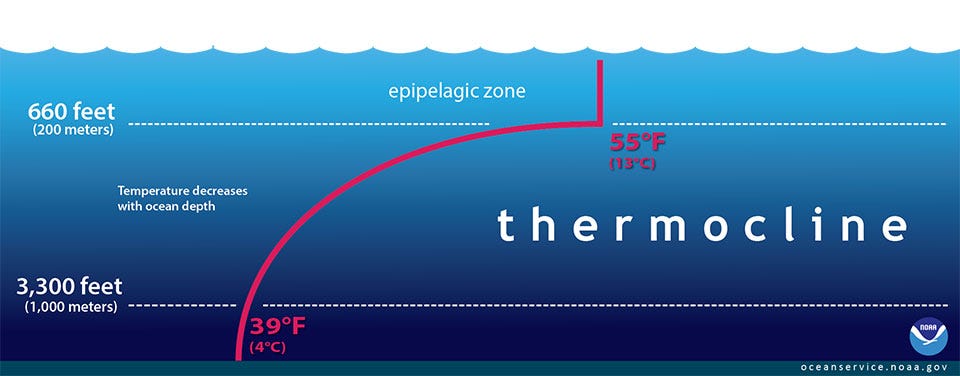

I should probably back up a bit at this point. An actual thermocline is a feature of deep sea temperature. As you go down, the temperature drops steadily, until you hit the thermocline, then suddenly. Here’s Rob’s explanation of it:

In the ocean, temperature decreases with depth: the deeper you go, the colder it gets. But sometimes, what’s called a thermocline forms: a temperature barrier, a point at which the temperature changes rapidly. Go above the thermocline and the water is warm; pass beneath it, and it’s suddenly cold. This can have huge ramifications for life in the ocean, preventing the passage of oxygen and nutrients past the barrier.

Trust

In his Twitter thread, Gareth Edwards uses this as a metaphor for trust:

The Trust Thermocline is something that, over (many) years of digital, I have seen both digital and regular content publishers hit time and time again. Despite warnings (at least when I’ve worked there). And it has a similar effect. You have lots of users then suddenly… nope… So why does this happen? As I explain to these people and places, it’s because they breached the Trust Thermocline.

The way this works is because users have some sunk costs (time, habit, emotional commitment, familiarity) with the media they use. They don’t just suddenly up sticks and leave when the product gets worse or the cost keeps nudging up. But there comes a point where their irritation exceeds the value of the service:

(T)hey’ll only move when they hit the Trust Thermocline. The point where their lack of trust in the product to meet their needs, and the emotional investment they’d made in it, have finally been outweighed by the physical and emotional effort required to abandon it.

But once they go, they don’t come back again.

Complex systems

In some ways this is a product of a complex system. And it is one of the reasons why people try not to perturb complex systems too much. It is worth expanding on this slightly. One of the distinctions in the systems literature is between ‘complex systems’ and ‘complicated systems’.

Complicated systems are highly predictable; complex systems are the complete opposite… Complicated systems, such as a car engine or a 747 aeroplane, are made up of parts that work together to achieve the desired outcome. Crucially, everything can be mapped out and (if we invest the necessary time) understood… In complex [systems], it is almost impossible to predict what will happen when we change something, even in cases where there are only a few parts.

Destroying HAL

Anyway, one of the implications of this is that you can’t know the point at which complex systems start to behave differently. Adam Roach noted that various Twitter systems had already started to behave differently:

One of the fascinating things is watching Twitter’s behavior change, hour after hour, as various microservices go offline… It’s like the end of 2001 when Dave is destroying HAL and HAL keeps on going, just gradually degrading, but continuing to work as far as his remaining capacities allow him to… But it’s only a matter of time before a core function is gone, and no one on staff knows how to get it back up.

Degrading gracefully

The system, in other words, is for the moment degrading gracefully, at least until it simply topples over. Joe Bak-Coleman had a thread on the issues in managing complex systems, and what to look out for:

If I wanted to keep an eye peeled for failure I’d look for a phenomenon known as “critical slowing down”. Systems about to transition will take longer and longer to get back to normal. Ad sales, latency, etc.. Will it? This happened to Digg after a large shift. Digg went from influencing the flow of internet traffic (the “digg effect”) to a ghost town after a big redesign caused cascading failures across its code, then userbase and ultimately advertisers.

Bak-Coleman says he doesn’t know if this is going to happen to Twitter, but he’s in good company. The scale of redundancies and departures means that that whole teams have left, as The Verge reported:

Remaining and departing Twitter employees told The Verge that, given the scale of the resignations this week, they expect the platform to start breaking soon. One said that they’ve watched “legendary engineers” and others they look up to leave one by one.

There’s quite a lot more detail in the story.

Bak-Coleman’s assessment: Musk’s “doing everything I could think of break it or any complex system.” And what might tip it over the edge? Well, maybe football’s men’s World Cup, which starts this weekend, since it always creates large surges in Twitter traffic.

There are many differences between SpaceX and Tesla, on the one hand, and Twitter on the other. But one of the biggest ones is that both SpaceX and Tesla involve complicated systems. Twitter is a complex system.

——-

On Mastodon, I am @nextwavef@mastodonapp.uk. A version of this article was also published in two parts on my Just Two Things Newsletter.